‘Happy Women’s Day!’ This is how Jenny Holzer greets me when I meet her on 8 March at the Guggenheim Bilbao, where she is in the middle of installing a career-spanning exhibition. She is brandishing a white T-shirt, a gift from the museum, on which are printed the names of women artists whose works are in its collection, Holzer included. In mostly text-based work over the past four decades, the artist has taken on the AIDS epidemic, conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq and Syria, and gun violence, among other subjects. But it is her statements about women’s experiences, ranging from the joyful to the traumatic, that have a particularly strong resonance today. When in October 2017 a group of artists and art workers organised in response to the growing conversation about sexual misconduct in their field, it was a phrase from a work by Holzer – ‘Abuse of power comes as no surprise’ – that became an emblem for the group, and gave it its name: We Are Not Surprised.

Untitled (Don’t Talk Down to Me) from Inflammatory Essays (1979–82), Jenny Holzer, photograph documenting the project in New York in 1983. Photo: Jenny Holzer; courtesy the artist; © 2019 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/VEGAP

The phrase comes from Holzer’s earliest series – the Truisms of 1977–79. She wrote some 300 short sentences, from the now well-known ‘Abuse of power…’ to more playful or more contentious sentiments such as ‘Morals are for little people’ and ‘Loving animals is a substitute activity’. These were printed on posters, typed in capital letters in an unfussy font, and Holzer then went around illicitly wheatpasting them on walls in the streets of Lower Manhattan. She had just moved to New York to embark on a year-long independent study programme at the Whitney, after an MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design. This was her first public project, so to speak. It was intended, ‘In a perhaps bold, 20-something way’, Holzer tells me, as ‘a survey of belief, and so I tried to write them from as many points of view as possible, some tender and some homicidal’. The texts of her next series, the longer and more extreme Inflammatory Essays (1979–82), were disseminated in the same way by the then-unknown artist, who remained anonymous to everyone except for ‘a few friends and occasionally the police when they would find me out with my posters. But they didn’t ask me my name’. Holzer’s big break came when the artist Dan Graham came across one of her posters. ‘I’m not exactly sure how, but he asked around and found me. I like his work very much, so I was ecstatic and proud.’

Is there an irony, I wonder, in using words from a work as slippery in tone as the Truisms as a straightforward slogan, as the We Are Not Surprised group has done? ‘I am delighted that some [of the texts] – not the dreadful ones – but some can be of utility, especially for things to do with the rights of women. There are some people in my family who were genuinely useful, like a surgeon and a nurse,’ Holzer says with a laugh. Throughout her career, she has repeatedly returned to existing series of texts, repurposing them in different formats. In the 1970s and ’80s, they would be printed on T-shirts and condoms, posters and plastic cups, inscribed on small metal plaques and stone benches, hijacking the electric billboards of Times Square. As Holzer’s reputation grew – in 1990 she became the first woman to have a solo show at the US pavilion at the Venice Biennale – more technically ambitious forms emerged. There are the sculptural installations made with LED signs, a spectacular waterfall-like version of which is on permanent display at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. And there are the laser and xenon light projections, which have appeared on landscapes and buildings from waves and mountains in Rio de Janeiro to Blenheim Palace. The texts themselves range from wry observations and advice on modern life, spoken by an anonymous ‘I’ to a universal ‘you’, to monologues with more clearly identifiable voices. Laments (1989), for example, consists of 13 texts imagined as ‘voices of the dead’ – ten adults, two children and a baby, affected by AIDS; Mother and Child (1990), created shortly after the birth of Holzer’s daughter, is written from the perspective of a new parent.

Installation view of The Venice Installation: The Last Room, showing texts from several series, (1990), Jenny Holzer. Photo: Salvatore Licitra; © 1990 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

It can be a puzzle to place Holzer – is she a poet, or a sculptor, or an installation artist? ‘I like to compose the presentation of language,’ she tells me. ‘I like to make the language spatial. I like coming at it various ways to various ends.’ In this sense, she is inspired by precedents including ‘the Dada gang’ and the concrete poetry of Apollinaire, which she recently read ‘again and again and again’, impressed by ‘how he represented the tension and ghastliness of war without being a preacher’. How does she pick which texts go with different formats – some so ephemeral, and some so emphatically permanent? ‘Some of the writing is relatively versatile. The Truisms are shameless; they’ll go happily everywhere, pretty much. But other things are meant to be read only in projection, only at night, only fleetingly, only with a group of people you don’t know, maybe only once, encountered by surprise. Other times, especially if I find a text notably moving or dire – in a pertinent way, not in a gratuitous way – I’ll think, “This should be in stone, somebody should find this again, even if it’s a Martian.”’ Stone is a recurring material in Holzer’s public memorials, such as the Erlauf Peace Monument in Austria (1995), which consists of engraved plaques and a bed of flowers surrounding a pillar that beams light in the night. But it appears indoors, too – as with the Laments, first exhibited at the Dia Art Foundation, where they were engraved into 13 stone sarcophagi, as well as appearing on LED signs and in a printed publication.

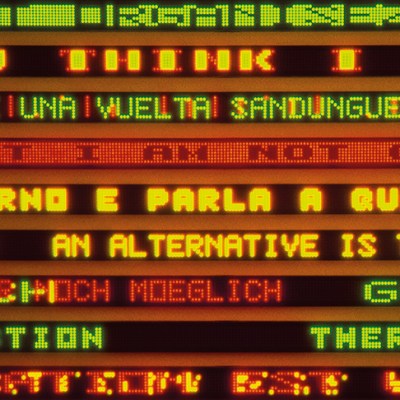

Survival: Use what is dominant… (showing text from Survival, 1983–85) (1989), Jenny Holzer Photo: Larry Lame; © 1989 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Around the early 2000s, Holzer stopped writing her own texts and started using the words of other people. Sometimes she asks friends, such as the poet Henri Cole, to contribute their work or to offer recommendations; Cole, whom she met at the American Academy in Berlin in 2000, ‘has been kind enough to give me an adult education in poetry’, she tells me. It was his idea, she says, to borrow Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself for her contribution to the New York City AIDS memorial in 2016, a spiral of granite paving stones carved with selections from Whitman. She reads voraciously, ‘Often with the television on so I can get info from the news and have Ginsberg [at the same time]. What a rich life!’ She has also worked with a number of charitable organisations including Save the Children and Human Rights Watch, using first-person testimonies from refugees, victims of torture, and many others. Holzer has long collaborated with her peers – in the 1970s in New York she was part of Collaborative Projects (Colab), with other artists including Tom Otterness and her future husband Mike Glier; in the 1980s, she worked with the graffiti artist Lady Pink to make colourful, large-scale paintings with texts from her Survival series (1983–85). Her move away from writing was partly driven by this tendency towards collaboration, she explains, as well as ‘the desire to have and to proffer so much more than I could generate by myself. It was a late epiphany but it was an epiphany. It’s like, “I can’t do all that!” And I can’t do justice to it. By the time we have 30 or 40 or 50 people who are earnest and bright and aching and wise, that’s what I want to give.’

The notion of art as a contribution, a public service of some kind, matters to Holzer. She agrees that this is probably connected to what she calls her ‘utility guilt and envy’. ‘That is a recurrent impulse. When something happens in the world, if I have an idea that can be properly responsive and perhaps of some use. Not necessarily a cure or a solution but at least an offering: here is something troubling, perhaps awful, whatever might we do?’ The situations she chooses to address are all things, she says, that ‘she’s relatively sure about’, whether because she has educated herself through the news and doing research or because she has lived directly through them, as with the AIDS crisis that devastated the artistic community of New York in the 1980s and ’90s. Then there’s ‘that woman thing’: ‘I have some first-hand knowledge about that, as do my friends and relatives. You don’t have to go hunting for that one. It’s daily, it’s in so many people’s history, including mine.’ And ‘So I want to show it and try to set it up so the viewer might have the right sort of feeling and impulse to address it in his or her way. Or at least know it.’

ON WAR (2017) (showing text from The Not Forgotten Association), Jenny Holzer, photograph documenting the projection at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. Photo: Samuel Keyte; text: © 2017 by The Not Forgotten Association. Used with permission; artwork: © 2017 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The desire to make things visible is perhaps why so much of Holzer’s work, from posters to memorials, has taken place in the public sphere – or, when it appears in museums and galleries, in forms associated with outdoor space such as benches, plaques and LED signs. It also makes sense of her frequent decision to have her texts translated into various languages; in the show in Bilbao, several key works are being presented in Spanish and Basque, and some in French and German as well. But for Holzer, this isn’t necessarily enough – she wants to reach people beyond the usual museum-going public. That’s why she tries, whenever she can, to include some kind of outside element in her exhibitions – in this case, a ten-day light projection. ‘Even though some people will know it’s happening, others will just be out for a walk and find it – and that’s my favourite, when you’re like, “Oh, the dog has to go out… What’s that?” My work was anonymous for the longest time and still is, in part, with the projections. That’s on purpose because I want people to attend to the content and maybe only in a little way wonder who did that and why.’

Water board (showing text from a US government document) (2009), Jenny Holzer. © 2009 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

It may be surprising, given this sentiment, that for the last decade Holzer has devoted a great deal of her time to painting, a medium she last explored when she was still a student in the early 1970s, enamoured with the work of the great Abstract Expressionists: ‘Rothko, Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt’. ‘I recognised that I failed with painting on the first try. That was clear,’ she says with characteristic self-deprecation. ‘But I didn’t want to give up.’ Then 9/11 happened and, in 2003, the US-led invasion of Iraq. Seeking to ‘learn what I wasn’t always finding in the press’ about the invasion, Holzer found a new source for her work: declassified documents in governmental archives, which had been released under the Freedom of Information Act and redacted to varying degrees. Her canvases reproduce these documents. Some are screen-printed and covered in oil washes (a nod to Warhol), others meticulously hand-painted by Holzer and her assistants. While there is often a shocking level of detail about interrogation tactics or injuries suffered by detainees, other documents have been so extensively redacted as to create beautiful abstractions – at least in Holzer’s renderings, which present the stacks of blacked-out text as blocks of colour, inspired by ‘Suprematist paintings, another favourite in addition to Rothko and the gang’. Holzer adds, ‘I thought that spoke to what you’ll never know.’

From poetry to painting, it’s clear that Holzer is as interested in other peoples’ art as she is in making her own. The exhibition in Bilbao provides evidence of this through a display of works by other artists, mostly drawings from her personal collection, built ‘gradually and very late’ because for a long time, ‘It seemed presumptuous, and somehow unholy, for an artist to buy something by somebody else.’ There’s a study of sheep and birds by the 19th-century animalière Rosa Bonheur (when she was a child, Holzer thought Bonheur was the ‘cat’s miaow’); a portrait by Mary Cassatt (Holzer was drawn to her depictions of motherhood); an enigmatic drawing by Paul Klee (‘I was interested in the unclassifiable’); one by Natalia Goncharova (‘I was again quite curious about the Russians’). There are also many works by artists she has considered friends, from Louise Bourgeois to Nancy Spero and Kiki Smith: ‘I wanted to know my friends better, my contemporaries, it’s a nice way to have them around without bothering them.’ It’s an eclectic collection, and one which seems to reflect Holzer’s approach to her own work, moving deftly between mediums, sources and subject matter. ‘I’m not especially bright but I am active and curious,’ she jokes. ‘I go to many places all the time.’

Shifting to Softer Targets (2014–15), Jenny Holzer. © 2019 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Certainly, Holzer is not one to stand still. Over the past couple of years, while continuing to paint declassified documents, most recently in watercolour, and to work with existing texts by herself and others, she has returned to the act of writing – ‘to my everlasting surprise’. This first took the form of a series of very short texts in response to the Parkland school shooting on 14 February 2018, which she put on LED billboards mounted on trucks that were driven out to cities across America. Starkly set in white letters on black screens, these texts – ‘DUCK AND COVER’, ‘STUDENTS WERE SHOT’, ‘SHIELD ME’, ‘IT IS GUNS’ – once again insist on being seen, and hopefully heard. (Subsequent truck campaigns focused on the mid-term elections last November, and World AIDS Day on 1 December.) The trucks are also an example of Holzer’s persistent search for new forms to convey her work, which extends to her exhibition in Bilbao and beyond. In Frank Gehry’s cavernous spaces she will show a group of LED sculptures animated by robotics for the first time, allowing them to ‘move and literally occupy more of the spaces’. She has recently started dipping her toes into augmented and virtual reality, which she thinks could be an effective way of extending the reach of her light projections. ‘Just the way we began with the electronic signs, we wanted to be where people look. Today, everyone’s looking at their tablets or phones.’ These latest and in-progress works ‘are not as effective as I’d like them to be yet’, she adds. ‘But we’re strivers!’

IT IS GUNS (2018), Jenny Holzer, photograph documenting the project in Washington, D.C. Photo: Catapult Image; © 2018 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

‘Jenny Holzer: Thing Indescribable’ is at the Guggenheim, Bilbao until 9 September.

From the April 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.