Now that the Victoria and Albert Museum has 145 galleries and more than 2.3 million artefacts, it can be hard to believe that the collection was started from scratch as recently as the 1850s. While Prince Albert and the museum’s first director, Henry Cole, are the most celebrated public figures in the early history of the V&A, there were also many private individuals whose contributions deserve to be better known. As curator of the collection built by the British-Jewish couple Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert, I started looking closely into the role played by earlier collectors with Jewish heritage. I soon found that there were several who had made an important contribution to the fledgling museum, which is not all that surprising since their donations coincided with the integration of some Jews into the upper echelons of British society over the course of the 19th century. In 1835, for instance, Sir David Salomons was elected the first Jewish Sheriff of London; in 1858, and after several attempts, Lionel de Rothschild was the first Jew to take a seat in the House of Commons; in 1873, Sir George Jessel was appointed Master of the Rolls. Yet other figures have been forgotten for too long.

The museum’s first major coup came after the death of the discerning collector and politician Ralph Bernal (1783/84–1854). He converted to Christianity, probably to be eligible to stand for Parliament, while both his parents were Sephardic Jews. They had made a fortune from trading in the West Indies and from owning slaves, and his grandfather, Jacob Israel Bernal, had been a warden of Bevis Marks synagogue in the City of London. The government refused Prince Albert and Cole’s request to purchase the collection in its entirety, but provided a generous allowance of £12,000 (the equivalent of £1.5 million today), which allowed the museum to buy a staggering 730 lots (out of 4,294) from the auction in 1855, including hundreds of pieces of Sèvres porcelain and the rarest pieces of medieval and Renaissance ivory, stained glass, pewter and maiolica. A few months later, these acquisitions were displayed at Marlborough House, the museum’s first premises.

Ewer (1340–50), Paris. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: © V&A

In spite of these generous governmental grants, the museum owned only 9,000 objects by 1863. This was not enough to put on meaningful exhibitions, so it turned to private collectors for help. Cole and the curator John Charles Robinson founded the Fine Arts Club to nurture lenders and, eventually, donors. This was the first British society for collectors of decorative arts and included, in Robinson’s words, ‘almost every connoisseur of note in the country, and a large proportion of the leading members’. Among them were several British Jews, notably Lionel de Rothschild. Thanks to the enthusiasm and generosity of the club’s members, in June 1862, the museum opened ‘The Special Loan Exhibition’ which presented more than 9,000 works from 553 lenders, many of whom deserve to be more carefully studied. Rothschild’s largesse was widely praised at the time: he lent hundreds of Renaissance and baroque ivories, ceramics and continental silver. One object was the subject of much press coverage: a jewelled silver-gilt, gold and mother-of-pearl partridge, which came back to the museum in 2008, as the mascot of the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection (and was selected as the heraldic symbol for their coat of arms).

Cup (1598–1602), Georg Rühl. The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo: © V&A

Isidore Spielmann (1854–1925) is another leading figure of the Jewish community worth remembering. He is best known as the co-founder of the National Art Collections Fund (today known as the Art Fund) but prior to that spurred on the idea of the Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition which opened in 1887. This was a milestone for the British-Jewish community and in the development of the study of Jewish ritual art. The V&A contributed at least 25 pieces of Judaica to the show. Spielmann was also president of the Jewish Historical Society of England from 1902–04 and honorary secretary of the Jewish Religious Union. Yet when he came to donate works to the V&A, he did not bequeath Judaica, but some of his best pieces of Dutch delftware, including a flower pyramid vase of c. 1695, which had been made for the 1st Duke of Marlborough.

Pyramid vase (c. 1695), Delft. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: © V&A

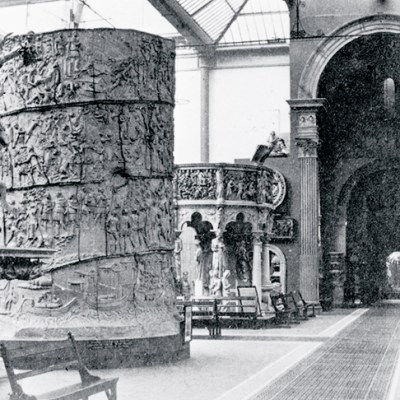

The museum also relied on a European network of dealers, many of whom were Jewish. The London-based dealership Durlacher Brothers was the first to gain the institution’s trust. The masterpieces it sold to the museum include a 14th-century silver-gilt and rock crystal ewer made in Paris; it also donated the flamboyant baroque bust of Charles II that now dominates the British Galleries. The Parisian dealer Siegfried Bing introduced the museum to two contemporary trends: art nouveau and japonisme. He sourced some remarkable pieces in both styles, notably a two-metre-high Japanese bronze incense burner, which was so expensive the Treasury had to authorise the purchase.

Incense burner (c. 1877–78), Suzuki Chokichi. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: © V&A

The figures I have mentioned are just a few from a much longer list of collectors, which is only starting to be compiled. Interestingly, although they were instrumental in helping to form the V&A’s encyclopaedic collection, they rarely contributed to the Judaica collection. The lives and attitudes of these donors, ranging from a Christian convert to leaders of the Jewish community, couldn’t be more different. Yet regardless of how these benefactors and dealers wanted to be remembered, their identity as British Jews has over time been forgotten and their contribution to not just the V&A but also other national and public institutions obscured. Ongoing research, notably with the ‘Jewish Country House’ project led by the University of Oxford, will hopefully identify reasons for this neglect and lead to this key chapter in the history of Jewish cultural philanthropy being more widely acknowledged.

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.