From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This impressive and unusual volume has been a long time in the making. The Jewish Country Houses project was first conceived in 2015 by a small team led by Abigail Green of Oxford University and Tom Stammers, then of Durham University, in collaboration with Juliet Carey of Waddesdon Manor. Since then, the project has grown hugely in scale and ambition, taking the form of a series of international conferences and interim publications and involving an increasing number of national and international partners, with a particular focus on curators and heritage practitioners. The project’s excellent website, which acts as a useful complement to the present book, describes its mission to take ‘country houses as a starting point for opening up a much broader intellectual agenda’, adding that ‘Our research sits at the interface between Jewish history, art history and heritage culture.’ But it is also an attempt ‘to transform visitor experience and public understanding of Jewish country houses, their collections and context, and Jewish history more broadly’.

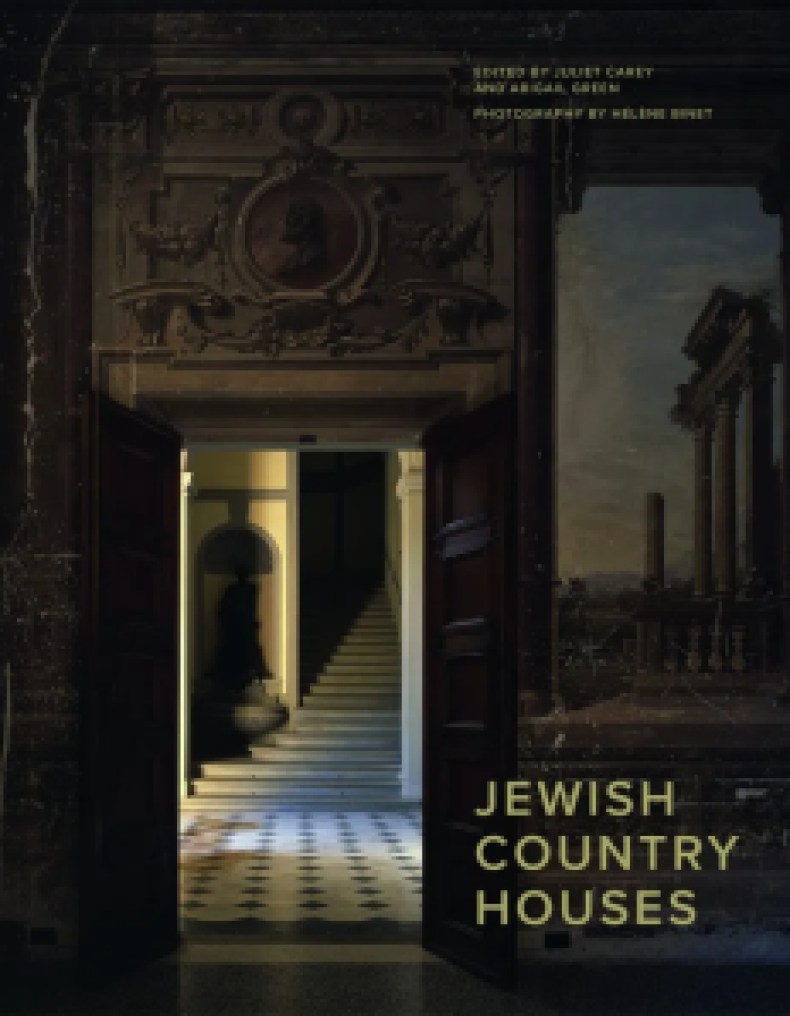

The editors’ claim that this is ‘a book of beauty as well as learning’ is well-founded, not only because of its design but above all because the haunting images by the acclaimed architectural photographer Hélène Binet are an integral part of the undertaking. Homing in on details, often captured at unusual angles, her unpeopled and poetic photographs vividly evoke the fragmentary, ruptured, transitory and often deeply painful nature of the histories explored in the texts. As Binet writes in her short but revealing essay, ‘intimating what lies beyond the frame is an important part of my work’.

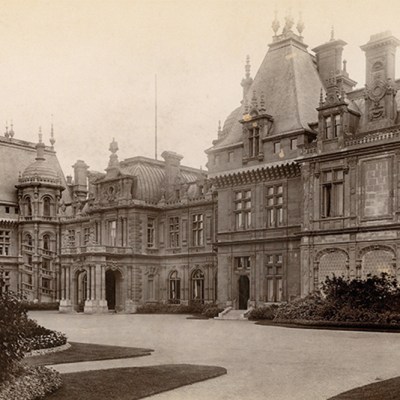

While the title of the volume could be criticised for implying that the concept of the ‘Jewish Country House’ is a monolithic and immutable one, this is immediately subverted by the image on the front cover, taken at the relatively little-known Villa ‘La Montesca’ in Umbria, built for the Franchetti brothers in the 1880s, full of suggestive shadows and spatial ambiguities. Inside, Binet’s full-page photographs are complemented by an interesting and diverse selection of relevant historical images, usually much smaller, many of them accompanied by illuminating extended captions. My one criticism of the layout is that not being presented with an image of the whole building at or near the beginning of each chapter can prove a little frustrating.

Crucial to the book is the long introductory essay by Green, Stammers and Carey (with Silvia Davoli and Jaclyn Granick), tellingly titled ‘A Jewish and a European Story’. Key themes include the elusiveness of the concept of ‘Jewishness’ – ‘never an exclusive category or identity’; the fact that ‘the Jewishness of all such houses inhered not in matters of style but in how they were used and perceived’; and that ‘“Jewish” country houses have escaped systematic study because they do not fit existing paradigms of the aristocratic landowner and the metropolitan Jew’. Importantly, the complexities of social status are expressed in these houses in both explicit and oblique, even concealed ways. While ‘these houses speak to an important moment in European history: the dream of belonging that preceded the Shoah’, they also stand as an eloquent reminder of the late entry – because of practical obstacles and deep prejudice – of Jews into the financial and cultural land-owning elite, and of the antisemitism that accompanied this. Last but not least, ‘This is not simply a book about country houses; it is also a book about Jewish memory in post-Holocaust Europe.’ To some extent this holds true of the British examples as well as those in continental Europe, particularly Trent Park, where ‘secret listeners’ (mostly Jewish refugees from Nazism) were privy to vital military secrets divulged by the German officer POWs resident here during the war.

This text is so densely packed with astute observations (and includes references to properties not covered in the following chapters) that I’m tempted to suggest that rather than trying to read the book from cover to cover, one should first digest this essay and then dip into the subsequent chapters as and when the moment seems right. Having said that, the 14 chapters by different authors on individual properties (all open to the public) in at least five different countries across Europe are also fascinating, both for their detailed scrutiny of each property in its national context but also for the links between them. Among these are the close personal connections between the different families, often through intermarriage (Sir Edward Sassoon of Trent Park, for example, married Aline de Rothschild), but also the tendency to favour the same architects (for example, Gabriel-Hippolyte Destailleur), and often hybrid architectural styles, and the ways the houses and thus their owners were regarded by the outside world.

A minor criticism might be that the rationale for the ordering of these chapters isn’t entirely clear. Nor – given that the project has uncovered an astonishing thousand or so eligible country houses – are the reasons for devoting chapters to these particular properties. The definition of the term ‘country house’ also seems just a bit too elastic: does the stunningly modernist Villa Tugendhat, for example, on the outskirts of the city of Brno, really qualify here? Why are quite so many of Binet’s photographs devoted to the latter, while there are none by her of Torre Alfina and Champs-sur-Marne? A few points could have been explored further: the issues of orientalism and whiteness in relation to Jewishness, for example, or the irony inherent in the late 19th-century penchant for the decor of the Ancien Régime. Given the overall richness of the book, however, this feels like carping.

The book is a model of transnational collaboration: a visually beguiling volume that achieves a satisfying balance between erudition and accessibility. Happily, the project seems set to continue, having secured a two-year grant to ensure its legacy. I for one await further developments with great interest.

Jewish Country Houses by Juliet Carey and Abigail Green (eds.) is published by Profile Books.

From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.