With the media filled with interest rate hikes and other miseries, news of the opening of the Wedding Cake, a three-storey sculptural pavilion created by the artist Joana Vasconcelos for Waddesdon Manor, may have seemed frivolous.

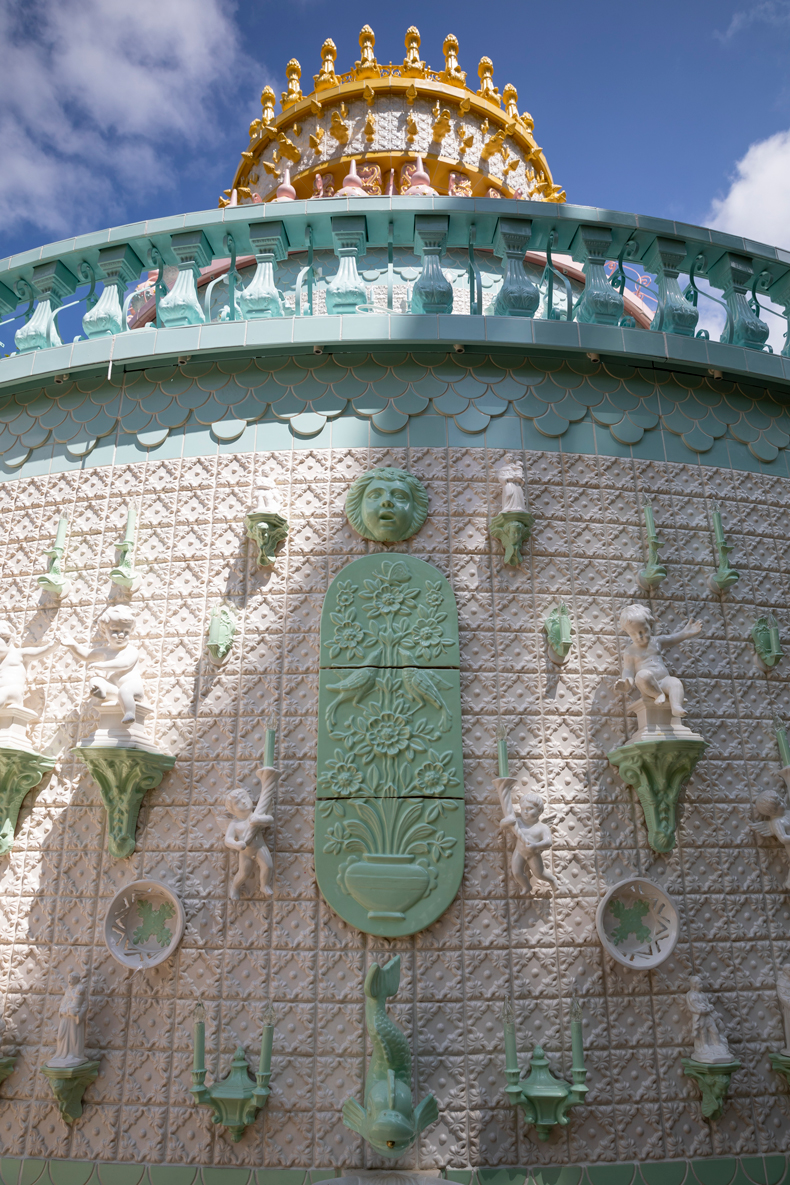

When confronted by the confection, however, any objections melt away. Three shimmering-white drums banded in sorbet hues lead up to a crown-like viewing platform. Each layer is clad with a carnival of decoration: water gushes from voluptuous fish into gleaming scallop shells rising to mermaids, urns and candle-wielding putti. The whole ensemble is formed of glazed ceramic, lending it a sugary, luminous quality. Inside, a star-studded dome supported by a colonnade radiates out into four bust-topped plinths under what resemble stalactites. The interior feels halfway between a neoclassical temple and a Turkish bath. It is preposterous, but delicious.

The interior of the Wedding Cake at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, designed by Joana Vasconcelos and completed in 2023. Photo: Chris Lacey

All this leads to the question: what is it? According to the press release, it is at least part folly. It certainly meets my working definition: an architectural structure in a beautiful spot, the style of which is unnecessary for its limited function – in this case, wedding receptions. But where does it fit into the canon of folly-building?

Vasconcelos names several follies as inspiration, including the Elizabeth Lookout in Budapest and the Temple of the Four Winds at Castle Howard. The Elizabeth Lookout, a fairy-tale Gothic-ish belvedere, was intended to strike awe into the viewer, while the classical Temple was designed to enhance the Elysian landscape. Allusions to the Temple are seen in the Cake’s dome, busts and symmetry inside, as well as in its baroque paraphernalia. In Britain, belvederes were often constructed in the ‘Strawberry Gothic’ style, an idiosyncratic synthesis of classical and Gothic that allowed for experimentation. Something similar is happening at Waddesdon. Perhaps the correct term should be ‘Cake Contemporary’.

The Elizabeth Lookout, Budapest, designed by Frigyes Schulek and completed in 1911. Photo: Akos Nagy

Between these two largely 18th-century ingredients, there are more subtle flavours to this edible-looking building. It alludes to the origins of follies in Renaissance banqueting houses, designed for consuming dazzling desserts – often in the form of sugar sculptures. The East Banqueting House in Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, with its twirling chimneys in buttery limestone, is a good example. Given the Cake’s abundance of aquatic imagery, there’s something of the grotto about it – a rustic variant of the ornamental temple, swirling with shells (at Stourhead House in Wiltshire, for example). The Portuguese artist’s conspicuous use of tiling – now indelibly associated with her homeland, but originally from Islamic Spain – hints at the more ‘exotic’ follies that were common in the later 18th century, such as the now-demolished mosque at Kew Gardens in London.

Typology aside, the Cake also displays some key traits of the folly. As a structure where form is often prioritised over function, a folly can act as a portal into a period’s visual culture, as well as a space for a designer to experiment. As a luxury building that looks good enough to eat, Vasconcelos’s Wedding Cake is an outsized symbol of the consumerist society in which we live. By virtue of its ceramic-clad surfaces, it is also an implicit challenge to the traditional hierarchy of building materials, whereby stone is valorised more than clay.

Ceramic ornamentation on the Wedding Cake at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, designed by Joana Vasconcelos and completed in 2023. Photo: Chris Lacey

Follies are also often jokes or metaphors. The Temple of Venus at West Wycombe Park is a classical temple on top of a rocky hollow. These represent the Palladian house above, its infamous Hellfire Caves below, and, through the entrance’s titillating resemblance to female genitalia, the shenanigans that took place within them. At the Cake, visitors standing at the summit become its frosted figurines. On a more sophisticated level, it is a satire of Waddesdon, zenith of the fabulously extra ‘Goût Rothschild’ that is as unexpected in rural Buckinghamshire as the Cake is in its English park. The Cake is also a celebration of the Manor, a trove of European art – especially of the exquisite porcelain collections that adorned its dining table. It was built to entertain Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild’s friends, including many politicians, at his opulent weekends. The Cake is already playing its role, having been opened by the President of Portugal as part of the Portugal-UK 650 anniversary, celebrating the world’s oldest diplomatic alliance still in force.

Rushton Triangular Lodge, Northamptonshire, designed by Thomas Tresham and completed in 1597. Photo: Historic England Photo Archive

Cynics could ask why Waddesdon needs another folly. It already has everything – from the adjacent ornamental dairy to the RIBA-hailed Flint House. But to me, the Cake belongs in the top tier of follies: the personal folly. It does not simply celebrate Waddesdon, but the present Lord Rothschild’s incredible transformation of the manor and gardens, patronage of Vasconcelos and commitment to our national artistic life. It reminds me of my favourite folly, the casket-like Rushton Triangular Lodge in Northamptonshire. Built by the architecture lover Francis Tresham in 1597, its obsessive use of the number three throughout is both a pun on his name, ‘Tres’, and a testament to his persecuted Catholicism through the Holy Trinity. Both are ‘Temples of Love’, as Vasconcelos describes the Cake. In these dark days, I arrive sceptical, but leave refreshed – and wanting a second slice.

The Wedding Cake at Waddesdon Manor is open for guided tours until 26 October.