From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

John Constable was 20 when, in March 1797, he wrote with a heavy heart to his friend J. T. Smith: ‘I must now take your advice and attend to my father’s business, as we are likely soon to lose an old servant (our clerk), who has been with us eighteen years; and now I see plainly it will be my lot to walk through life in a path contrary to that in which my inclination would lead me.’

For six and a half years after he left school in 1792, Constable’s future hung in the balance. His ambitions to become an artist were pinched by family pressures and came close to being nipped in the bud. According to the Suffolk poet Ann Taylor, who met Constable when she was in her teens, this interesting young man who was often seen with his sketchbook in the lanes and fields around East Bergholt was regarded locally as a ‘hero in distress’. It was said that his father, Golding Constable, ‘wished to confine him to the drudgery of his own business’ – a fate that seemed ‘unspeakably barbarous’ to her and her friends. It was only when John’s younger brother Abram reached the age of 16 and agreed to take responsibility for running the family firm that Constable was free to go to London to train at the Royal Academy Schools, where he was admitted as a probationer in March 1799.

Drudgery or not, Golding’s trade was lucrative. He owned two watermills, a windmill and some 36 acres of land, and ran a complementary transport business. His barges carried sacks of flour from his mills down the River Stour, and his brig took them round the coast and up the Thames estuary to London to be sold. Not long before John was born, Golding was able to build an impressive, four-square mansion for his family in the centre of the village, close to the church. He called it East Bergholt House.

To many, John’s position between 1792 and 1799 was enviable. To him, however, it was not only disappointing but also peculiarly frustrating. He had an older brother who would in normal circumstances have stepped into his father’s shoes, but Golding Junior had a learning disability and suffered from debilitating fits. Abram was only nine when John left school. As their father was not the sort of man to leave the future of his business uncertain, any more than his corn unharvested or his barges uncaulked, the spotlight fell on John, who was duly kitted out in the miller’s traditional white coat and hat and sent to the windmill on East Bergholt Common to learn how to manage the machinery and read the sky. The practical part of Constable’s training would have involved induction into all aspects of his father’s enterprises, from overseeing cargoes off vessels and into warehouses at Mistley Quay to studying the maintainance of mills, barges, locks and towpaths.

According to Constable’s friend and biographer C. R. Leslie, Constable worked for his father ‘for about a year’, and ‘performed the duties required of him carefully and well’. Was it really so short a time, a fraction of the period he lived in his parents’ home in suspense about his future? Leslie was assembling his narrative from remembered conversations with Constable; he did not interview him formally, as a professional biographer would. And Constable himself, some 40 years later and in general conversation with a friend, could well have been vague about the extent of his youthful involvement, or even sought to downplay it. The Golding Senior who emerges from his few surviving letters – careful and deliberate – does not sound like a man who would have been happy to allow a capable son to wander around sketching all day when there was a business to be managed. He had brought up his sons to work. It is hard to imagine that he did not find at least ad hoc tasks for his middle boy during those uncertain years of the 1790s. Constable’s recent biographer James Hamilton has pointed out that as he acquired the name ‘the handsome miller’ locally at this time, he was evidently regarded as just that – a miller. It seems likely that during those six and a half years he was balancing his art with the demands of the family firm, which naturally fluctuated with the weather and the season. Even if his duties were light and predominantly administrative, his habits of mind would have been shaped by an environment in which daily conversation revolved anxiously around the weather, the state of the crops and the height of the river. In time to come it set him at an angle to other landscape painters and their ideas about what constituted an attractive view; but it also gave him the ability to see things that others missed. His art, he once said, was ‘to be found under every hedge and in every lane, and therefore nobody thinks it worth picking up’.

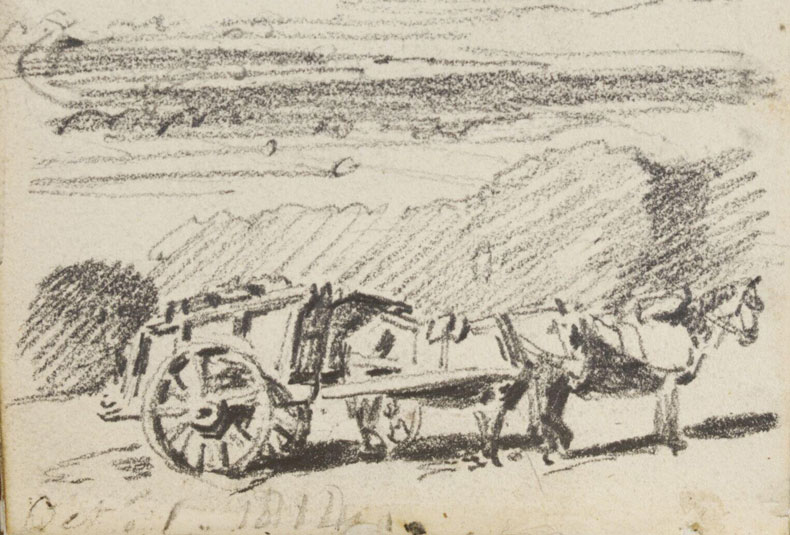

Open his sketchbooks and Constable’s preoccupation with ploughs, carts and barges is impossible to ignore. His oil paintings took his insider’s view of the working landscape to the gallery walls, sometimes foregrounding activities the purpose of which is not immediately obvious. Some have an apparently riddling air: why is a heavy, working horse standing in a barge on a river? Answer: the towpath switched banks at that point on the Stour. What about that one performing an unlikely jump over a barrier on a towpath? Answer: barriers were built along the path to prevent livestock from straying and tow-horses were taught to do this. At Royal Academy exhibitions, however, viewers must sometimes have stood in front of these paintings and wondered.

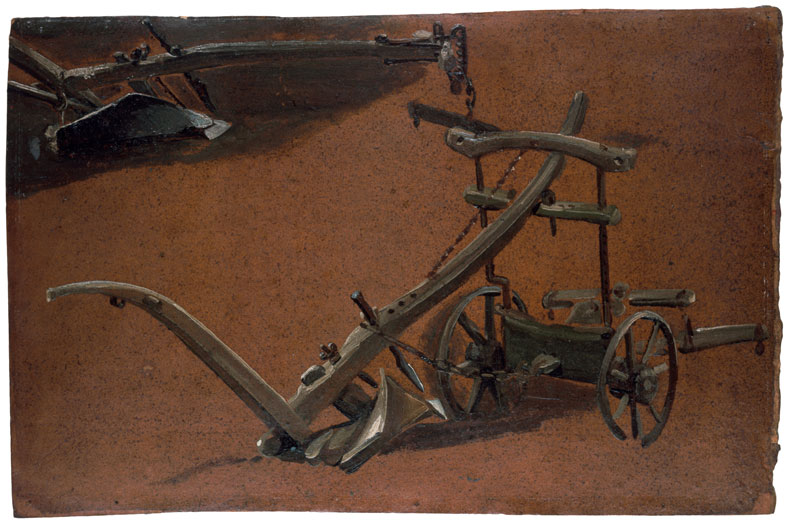

The rattle of agricultural nuts and bolts in Constable’s work increased sharply in volume in 1814, when it entered a short-lived but remarkable period of intense realism (see, for instance, his oil sketch of two ploughs, and a sketchbook from that year, both in the V&A). Between 1799 and 1816, the year he married, he lived and painted in London during the winter and spring, usually returning home to East Bergholt in June or July, where he would stay for around four months. During this time he would draw and sketch in the familiar lanes and fields. But working on a composition in his London painting room was not always easy and, in February 1814, the picture he would exhibit that summer with the title Landscape: Ploughing Scene in Suffolk was causing him particular trouble. The problem? The composition itself. It had been sparked by a tiny pencil sketch he had made from the boundary of East Bergholt’s Old Hall estate in July 1813: a panoramic view of the Stour valley and the distant village of Dedham. When his picture was scaled up on canvas, however, it lacked activity, what Thomas Gainsborough had called ‘a little business for the Eye’. So Constable solved it by adding, as he explained to his friend John Dunthorne, ‘some ploughmen to the landscape’ which was, he said, ‘a great help’. To his composition, perhaps; but for most viewers used to depictions of spring or autumn ploughing, it was a peculiarly unseasonal addition to a picture painted in the rich greens of high summer.

If the average exhibition visitor puzzled over this anomaly, any Suffolk farmer would have known exactly what it was about. Even though the ploughmen had arrived belatedly in this particular landscape, Constable was recording a long-established local practice – which was presumably why he added the words ‘in Suffolk’ to the title when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy. Just 10 years previously, the agricultural reformer Arthur Young had noted in his Farmer’s Calendar (1804) that heavy soil, if ploughed too early, remains ‘stiff and saddened’ and then ‘very difficult to be acted upon by any instrument’; the farmer’s ‘only chance is, to have abundance of patience’ and ‘avoid such spring ploughings’. What Young called the ‘clayey loam’ of Suffolk was particularly susceptible. The solution, summer ploughing, was far from ideal: it was hard work for both horses and men, because by then the earth had dried into great clumps, and hot days made it more gruelling still. A field treated in this way, which would be sown early with winter wheat, was known as a ‘summer-tilth’ or a ‘summerland’ – the title Constable eventually gave to the mezzotint after this painting in the set of prints he published in 1830–32, Various Subjects of Landscape, characteristic of English Scenery. Despite sounding as though it might refer to the appearance of verdant fields under summer skies, A Summerland had a precise agricultural meaning. When, however, in 1824–25 Constable painted a copy of Ploughing Scene, he gave it a more conventional appearance, choosing autumnal tones of grey and brown for the fields and foliage.

Another problem Constable experienced with his Ploughing Scene turned out to be the catalyst for a radical change of method. In his London painting room at the tail end of winter, he struggled to evoke the noonday heat of a summer’s day. ‘I must try and warm the picture a little more if I can,’ he wrote to Dunthorne in 1814. ‘It is bleak and looks as if there would be a shower of sleet.’ He saw that one way of tackling this was to paint outdoors in order to capture not just how a place looked, but how it felt, to feel the warmth of the sun and to smell the earth and the river. In September and October that year, back in East Bergholt, he worked on two paintings in this way. In the mornings he set up his easel on the edge of Old Hall park, not far from the spot from which he had drawn the landscape that became Ploughing Scene; and in the afternoons he went down to Flatford mill, where a barge was being constructed in his father’s dry dock. If one problem he had faced earlier in the year had been a lack of animation, in both places he found an abundance of it.

Boat-Building near Flatford Mill (exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815; now in the V&A’s collection) is Constable’s most audaciously workaday picture: its subject, a barge under construction, is not just a component of a landscape scene but front and centre. One craftsman sits in front of its mighty prow while another shapes a curved timber; a cauldron contains pitch to caulk its seams; and various tools of the barge-makers’ trade are scattered about, as though the other workers have just laid them down and gone off for their break. The painting is so detailed it could serve as a practical guide. It is as though the experience of working directly on to canvas outdoors had reconnected Constable to the industrial landscape he knew so intimately and given him the courage to paint the activities that most fascinated him, however unconventional they might look on the wall of the Royal Academy (from where, perhaps inevitably, the picture failed to sell).

The other painting on which Constable worked during the autumn of 1814 was his most audacious, full stop. Philadelphia Godfrey – the daughter of Peter Godfrey, who owned Old Hall, the grandest house in East Bergholt – was getting married later that year. Her fiancé, Thomas Fitzhugh, had commissioned Constable to paint a Suffolk scene for Philadelphia to take to her new home. The chosen view was from the edge of Old Hall’s park looking over Dedham Vale, with Dedham village and church in the distance. Did Fitzhugh or Peter Godfrey discuss the composition with Constable? It would have been strange if they had not. Did they walk to the fence and look with him? If they had, they would surely have asked the artist to rethink his viewpoint or at least to exercise poetic licence. A new feature of the landscape had appeared in the form of a gigantic dunghill – known locally as a ‘dungle’ – constructed over the summer and left to rot. Farm labourers were now busy shovelling out the manure and loading it onto carts so that it could be distributed onto arable fields. As a subject, Constable found it irresistible. He planned his composition around it, even making an adjustment from a preliminary sketch so that the dungle would be more central in the finished painting. In the middle distance the River Stour winds through the valley, but there is no mistaking the picture’s focus: a vast and ungainly dunghill, frilled here and there with weeds, its top touched by the rays of the morning sun.

A less appropriate wedding present would be hard to imagine. What Philadelphia thought, and where – or if – she hung it in her London home to remind her of Suffolk, are not recorded. For Constable, though, the dungle and the busy activity around it were every bit as interesting as a ripe crop; probably more, because they showed labour, skill and good husbandry in action. His choice of subject sprang from the same mentality that led him to paint the construction of a working barge while more conventional artists were painting fishing boats. His background in farming and land stewardship caused him to see landscape as a process, with past and future dimensions. A picture that could be interpreted as a gross insult from any other landscape painter of his generation sits more comfortably when understood within the context of the farming year, in which the autumn’s preparation of fields was balanced against the following year’s yield. Either that, or he and Philadelphia had history.

Constable’s own marriage in October 1816, after which he lived full-time in London, brought a change to his focus. After a final long stay with his wife, Maria, in the summer of 1817, visits to his beloved corner of Suffolk were brief and on family business. He returned to painting in the studio. There, a profounder sense of place filled the gap left by direct experience; Constable continued to paint Suffolk scenes, with his view from London seasoned by distance and enriched by memory and emotion. The grit in the oyster, however – his insistence on the importance of agricultural work in all its local peculiarity and technical detail – did not dissipate in the atmosphere of London but sat at the heart of his six-foot Stour scenes. It powers them like an electrical charge. Those uncertain years of the 1790s may have been ones of apprehension and worry, but the work from which he longed to be released was precisely what sowed the seeds of his future greatness.

Susan Owens’s upcoming book, Constable’s Year: An Artist in Changing Seasons, will be published by Thames & Hudson in January 2026.

‘Turner and Constable’ is at Tate Britain, London, from 27 November to 12 April 2026.

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.