On 3 February 1820, John Keats travelled to London on a day trip from Wentworth Place, his house in Hampstead. It was a stormy day and he hadn’t brought a coat. He returned that evening, having bought a cheap coach ticket that meant he had to sit outside on the journey, so by the time he got home, Keats, frail at the best of times, was a wreck. He stumbled upstairs and collapsed on his bed, coughing up a drop of blood that the young poet, a surgeon by training, recognised as arterial, and therefore indicative of tuberculosis. ‘I cannot be deceived in that colour – that drop of blood is my death-warrant. I must die,’ he told his friend and housemate Charles Armitage Brown. This episode was the beginning of the end of Keats’s dismally short, astonishingly productive and perennially romanticised life, which ended at the age of 25 in February 1821 – just over a year later. But perhaps the most tragic aspect of it was that, in that moment on the bed, Keats’s approaching death was probably one of the only things in his life that he could be certain of.

Keats’s life was characterised by precarity that began with his neglectful parents and continued with money troubles, family tragedy, anxieties about his intellectual inferiority and his poetic legacy and, of course, his patchy health. In December 1818, having abandoned his medical career to become a full-time poet, he moved in to Wentworth Place – a white-fronted house on the edge of Hampstead Heath that was divided into two parts, one of which was occupied by Brown and the other first by the writer Charles Wentworth Dilke and then by Fanny Brawne, with whom Keats would start a tempestuous romance. The 17 months he spent there were, as his 20th-century biographer Walter Jackson Bate wrote, ‘the most productive in the life of any poet of the past three centuries’, giving rise to works including the narrative masterpieces ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’ and ‘The Eve of St Agnes’, as well as his greatest achievement of all: the six odes of 1819. Among these is ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, which he wrote outside in the garden sitting under a plum tree over two or three hours in the spring of 1819. But his time here was cut short, too, at the request of Brown, who, in the summer of 1820, asked the sickly Keats to move out for a few months so he could rent out the house for a tidier sum.

Today, Wentworth Place is known as Keats House and is one home rather than two, the dividing wall having been knocked down in the 1830s. It became a museum in 1925, is now managed by the City of London Corporation and is this year celebrating its centenary. What is made clear in the display marking this anniversary is that, if Keats’s existence was dominated by uncertainty, the same is true of the house he lived in. In the decades after his death Keats’s connection to it faded from memory. In 1896 a plaque went up to mark the Keats connection, but nonetheless, in the early years of the 20th century the house was slated to be sold to builders. It was thanks to the Hampstead Borough Library Committee, along with help from the Morning Post and various literary figures including Thomas Hardy, W.B. Yeats and Amy Lowell, that Wentworth Place was saved: the committee managed to raise the funds to buy it instead and, by 1924, after a period of restoration, it was handed over to Hampstead Borough Council, who opened the museum the following year. Today, the house’s existence is secure, having been Grade I listed in 1950, but it could just as easily have slid into oblivion.

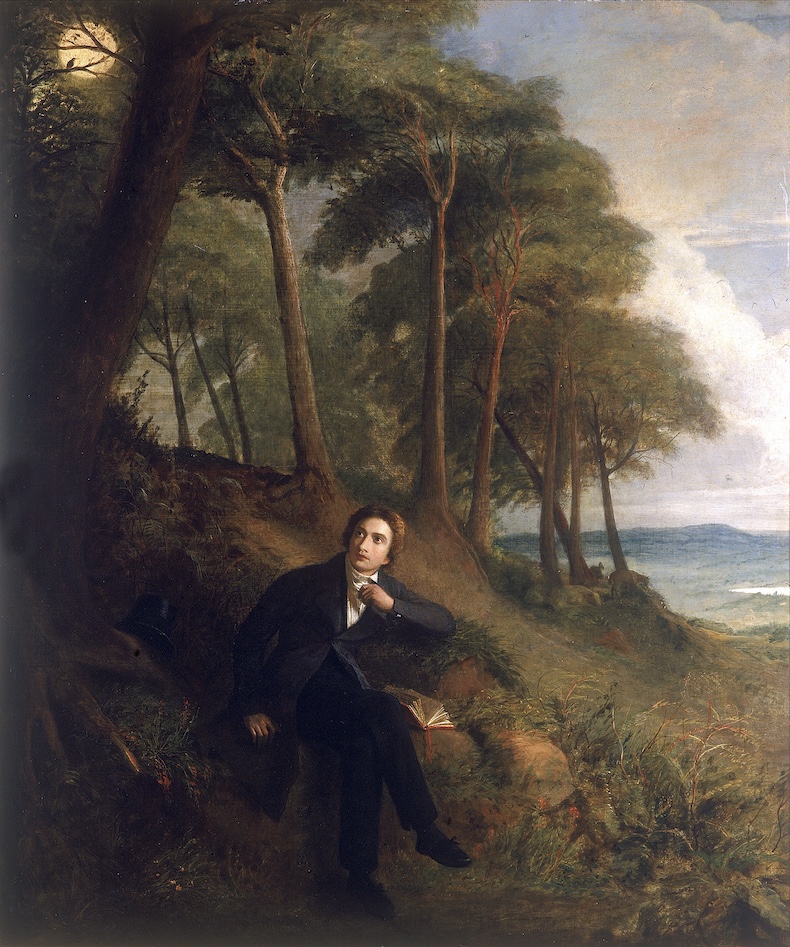

As a writer’s house, the museum strikes a balance between faithful curation and a sense of narrative. Upstairs, Keats’s bedroom is sparsely decorated, which gives the visitor space to imagine Keats collapsing down on the bed – a replica is there nowadays – on that fateful evening in February 1820. Downstairs in Keats’s parlour hangs a portrait painted by his well-meaning but oleaginous friend, the artist Joseph Severn (most paintings of Keats were done by Severn, which means that there aren’t many good paintings of Keats). It shows the poet deep in thought, a book open on his lap, sitting in the very same parlour, with the curtains drawn and a sliver of garden visible outside. The room itself has been arranged as it is shown in the portrait: the Shakespeare drawing on the wall, the carpet almost the same patterned red, even the two chairs arranged in the same haphazard manner. That drawing of Shakespeare is one of many artefacts in the house that give a sense of Keats’s status as a literary fanboy. It is easy to imagine Keats scrawling the feverish annotations shown in the dog-eared copy of Paradise Lost displayed here. In the same room we see a manuscript of his youthful sonnet ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’ (1816), in which he describes the sense of wonder he felt at reading George Chapman’s translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Wonder recurs again and again in Keats’s work: of all the great Romantic poets he was the most openly and passionately wide-eyed at the world around him, as well as being keenly aware of the inability of language to capture such emotions. His passion is what endears Keats so strongly to his devotees and, at the same time, what fuels his detractors; he could be characterised, if we’re being ungenerous, as a teenage poet frozen in time. One instance of Keats’s unfiltered passion came in January 1818, when he went to see his friend Leigh Hunt, who surprised Keats by producing a lock of John Milton’s hair that he had recently acquired. ‘I feel my forehead hot and flush’d,/Even at the simplest vassal of thy Power,’ Keats wrote in a poem he scrawled on the spot. There is something fittingly Keatsian, then, about the upstairs display at Keats House, which includes a cabinet of objects that were displayed at the opening of the museum a century ago – among them a striking life mask of Keats taken by his friend Benjamin Haydon, as well as an oval locket containing a lock of Keats’s hair, sandy blond and curled round on itself. Of all the objects in the house, this twist of hair is the one that most strongly elicits the feeling – at the risk of sounding a little too much like Keats himself – of communing with his spirit.

Keats never returned to Wentworth Place after he moved out in the summer of 1820. Advised by his doctors to seek a warmer climate to help with his worsening sickness, he made his way to Rome with the ever-present Severn by his side. There he died in pain, his tuberculosis not helped by his decision to self-medicate with mercury, with the worry he had sketched out in a famous sonnet of 1818 – ‘When I have fears that I may cease to be/Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain’ – having come to pass. In the years after his death Keats’s reputation was marshalled by his friends, including Severn and Percy Shelley, as well as later acolytes such as Oscar Wilde, who lauded him as a ‘divine boy […] slain before his time’. We are no longer in the era when this kind of unadulterated fawning holds water; Nicholas Roe and several other critics have led the charge in bringing Keats back down to earth through accounts of his bitterness, bad temper and propensity for cruelty. The reality is surely somewhere between these two characterisations. Keats House – which was only inhabited by the poet for a short while and is, today, as selectively curated as any other such museum – cannot give us the whole picture of the man, but it can help resurrect some sense of him that we cannot get from the writing alone.

‘Keats House 100’ is at Keats House, London, until 12 April 2026.