In 1963 Stephen Spender characterised John Piper’s already eclectic and unusual career, as ‘a fusion of a lifelong search for a contemporary idiom with a passion for tradition’. Stained glass – medieval, sacred and austere – presented the perfect challenge for the artist’s temperament. It had been an important part of Piper’s life since he first became interested in the history of English churches during childhood days spent biking around the Surrey countryside. He claimed, perhaps hyperbolically, that a copy he made of a panel of a 13th-century window as a student taught him more about colour than he had learnt before or since. As Piper was finding his way through the various schools and styles of interwar Britain, he became increasingly concerned about the popularity of abstraction leading to the eclipse of object-based art. The discipline of stained glass specifically had, in his own words, become ‘undernourished’, left to the dry typologies of archaeologists and insulated from contemporary trends by the conservatism of the clergy. Pictorial ingenuity had been neglected, since apprentices were unrealistically expected to be versed both in painterly processes and technical craft skills.

In Europe the story was somewhat different. Chagall, Matisse and Braque had each tried their hands at producing novel and interesting designs. Piper was desperate that there be a similar renaissance in the UK. His irreverent and inspiring treatise Stained Glass: Art or Anti-Art (1968) has an almost evangelical tone as he calls on the clergy ‘to be bolder’ and on art students to have new ideas, even if they were rubbish.

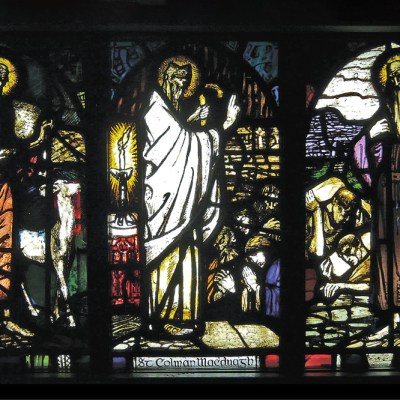

Two key figures encouraged Piper to deepen his relationship with stained glass and even begin making his own designs. The first was John Betjeman, who Piper met in 1936. This began the incredibly productive working relationship of artist/photographer and writer in the Shell Guide series. Betjeman recalled Piper’s remarkable energy, visiting more than ten churches a day. He was always photographing, sketching, painting and discussing; this allowed his knowledge of medieval arts and architecture to transform from that of a cataloguer to the sensitive appreciation of a ‘looker’. The seeds of an idea about not just recording these traditions but actually contributing to them began to take hold. The second was the stained-glass maker Patrick Reyntiens, who was introduced to Piper in the early 1950s through Betjeman’s wife, Penelope. At this time Piper had been approached by a friend of Betjeman to design a new window for Oundle School. Reyntiens became his collaborator. Their first test designs were produced a few weeks later, and Betjeman proudly declared it Piper’s masterpiece to date. Commissions at Eton College and in the newly built Coventry Cathedral soon followed.

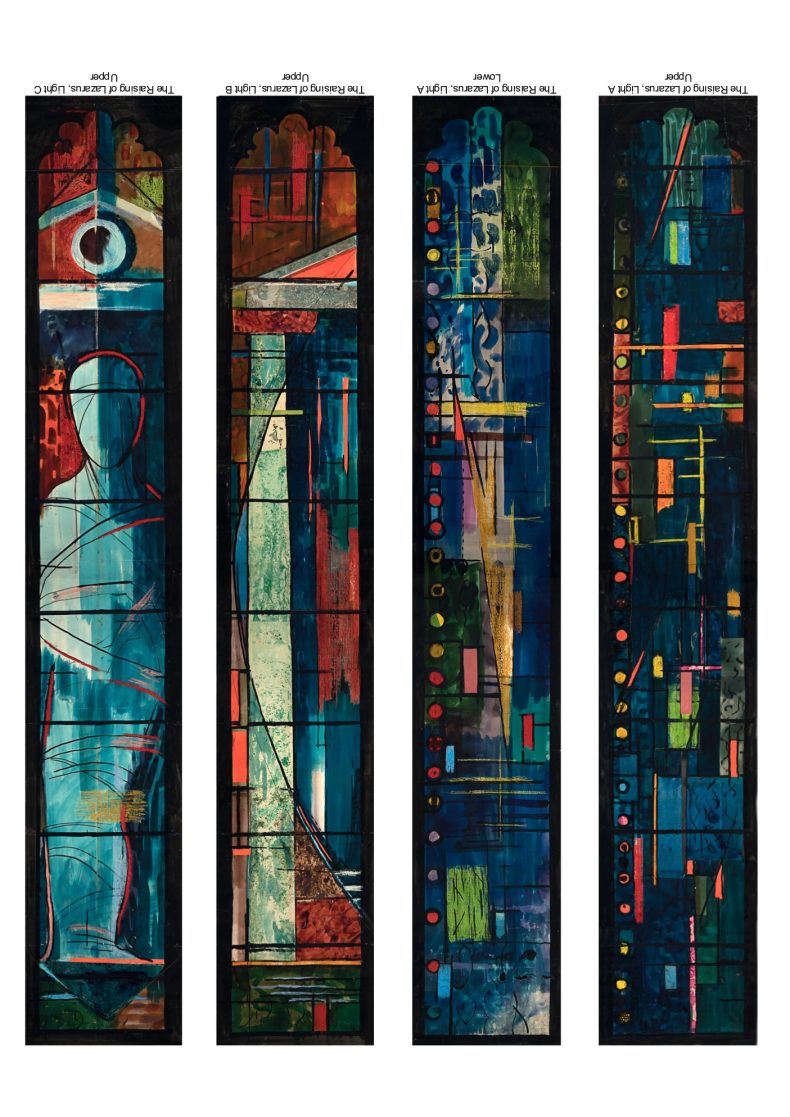

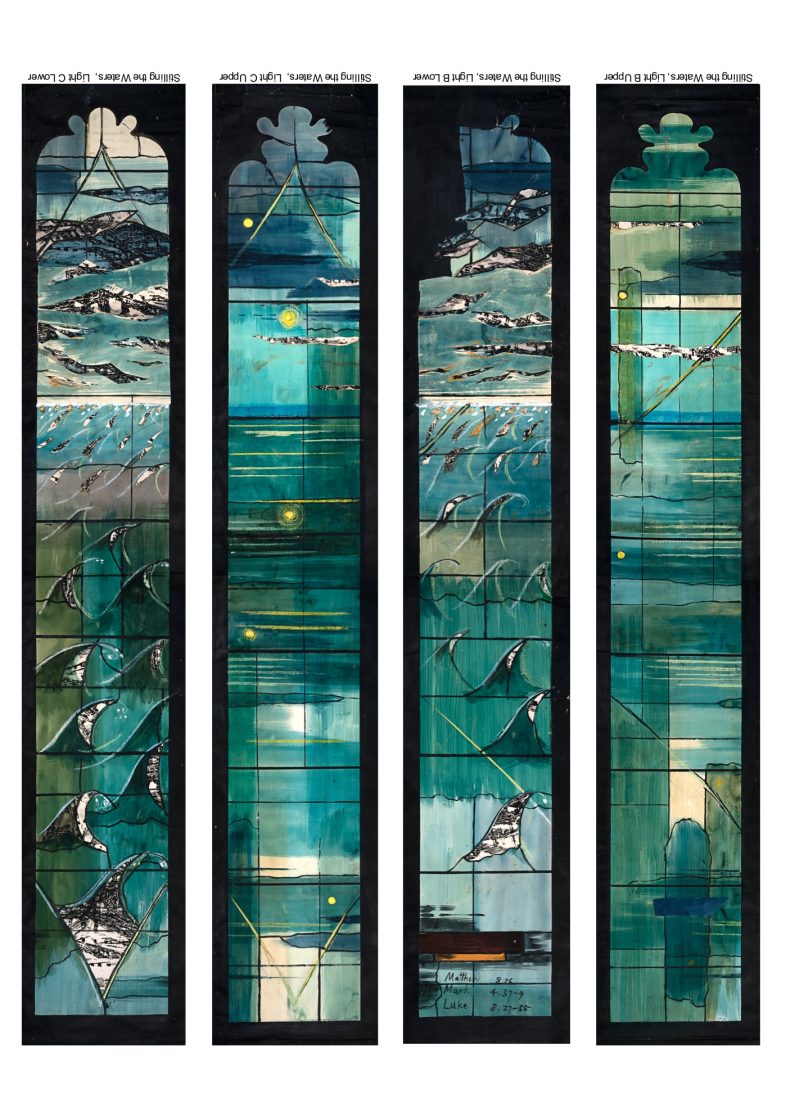

At this time Piper began to develop a philosophy of process. Collaboration was, of course, essential, as the artist’s designs were realised by the specialist. However, Piper warned of spending too much time in the glass-maker’s studio – he was adamant that the working relationship shouldn’t be too close. The painter’s cartoons had to be thought out in isolation as paintings, in and of themselves, before anything else. In the designs themselves, even if figurative, he was not so concerned with creating complex iconographies (which were there nonetheless) but with ‘glow and glory’. His designs were primarily about light and its conversation with space and architecture. Piper illustrates these ideas in a beautiful ekphrasis on the windows in his beloved Chartres Cathedral. It is a recollection of a cold winter’s morning visit: the figures in the windows he found incidental but the colours, the blues and reds gashing ‘like wounds’, and the light tunnelling on to the ‘cliffs of stone’ around were a source of endless fascination and wander.

As you look at the cartoons you can see these echoes reverberating through his work. Piper thought of the window in a painterly fashion, from small study to final cartoon. Tonal variance, crucial once translated into glass, was carefully considered. Spatial cohesion – such a challenge with projects of this scale – was maintained by laying designs out side by side. He used collage, chopping and changing, often layering different fragments together in an experimental way, all the while trying to tease out the most glorious arrangement of the different elements. The motifs themselves blend images we see across Piper’s work – the foliate head, the ruin, the air motif – with timeless sacred images of fish, crucifixes and poised hands. True to Spender’s estimation, this is work that is both modern and experimental, but rooted in a deep understanding of the medium and its history.

When John Betjeman died in 1984, it is telling that it was with a Piper stained-glass that he was memorialised. It is a small and delicate window in All Saints in Farnborough, depicting fish, the tree of life and butterflies. It stands as a wonderful tribute to a friendship that did so much to preserve and promote the history of stained glass and its present.

Lead image: used under Creative Commons (CC0 1.0)