The other week, I went to the opening of Waddington Custot’s new Joseph Beuys show, where I chanced upon a friend whose art-historical knowledge puts my own to shame. Pleasantries exchanged, she turned to the work and told me about a David Sylvester essay on the artist. I paraphrase here, but apparently the late critic anticipated Beuys’ exhibitions in the same way he prepared for exercise: ready for a healthy experience, but steeled for some bloody hard work.

In this instance, Sylvester needn’t have worried. This exhibition is a highly entertaining recreation of an episode that occurred during Beuys’s residency at Documenta 5, in which he turned a room in Kassel’s Fridericianum into an ‘office for direct democracy’. For 100 days, the artist sat in his space, debating politics with visitors and a few fanatical acolytes. At some point, Abraham David Christian, a student, challenged the artist to a boxing match, and Beuys willingly agreed. On the final day of the ‘office’, the fight took place, with Beuys representing ‘direct democracy’, and Christian ‘representative government’. I’m not sure what this says about political philosophy, but the former won.

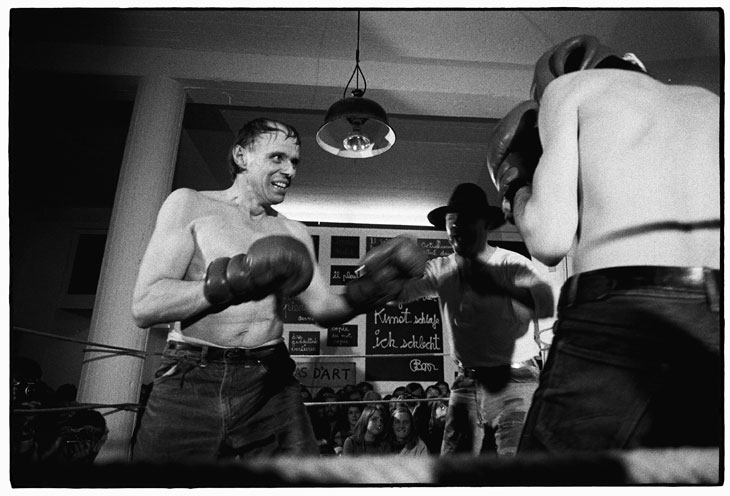

Boxkampf fur die direkte Demokratie (1972), Joseph Beuys.

On the evidence presented here – a film of the fight, notes, still photographs and the gloves used to slug it out – the event was a sweaty affair. Until I visited, I’m pretty sure I’d never seen an image of Beuys smiling before, but here he is, all the while perspiring like an ice cube under a blowtorch. Private gallery shows in the summer months can pull some silly stunts in order to provide a bit of fun – but this one is a masterclass in well researched, visually arresting and entertaining exhibition-making.

*

Le Moriband (1819), Théodore Géricault. Daniel Katz

Some memorable highlights from London Art Week. At Daniel Katz’s ‘Romantics to Rodin’ display (until 28 July), I was captivated by an unpainted prone plaster figure modelled by Géricault. Muscular yet defeated, he appears either at death’s door or reduced to emotional desolation. This wretched little figure served as a study for the artist’s masterpiece, Le Radeau de la Méduse. Stephen Ongpin, meanwhile, has an outstanding selection of drawings by Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo on show (until 26 July). I coveted everything.

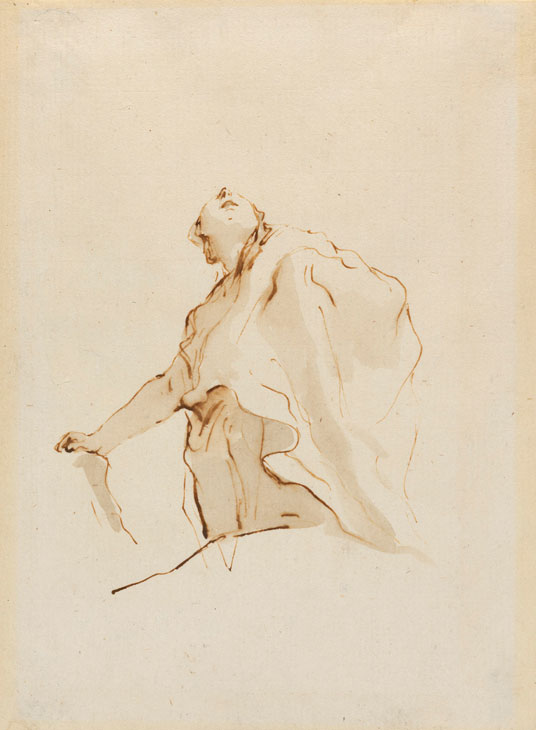

Reclining Figure on a Cloud (c. 1750), Giovanni Battista Tiepolo Image courtesy Stephen Ongpin

The discovery of the week, for me, was at St James’s dealership Bagshawe Fine Art. Amid a selection of 19th- and early 20th-century painting, one work stood out – a strange scene depicting a woman dressed in the shroud of the Virgin and presiding over a gaggle of infants. The children higher up the composition are presented naturalistically, but get more warped towards the bottom of the image. It is an unsettling mid-point between Stanley Spencer and Richard Dadd, troubling, yet utterly compelling.

This is the work of Mark Symons (1887–1935), an artist who trained at the Slade before, in the words of gallerist Nicholas Bagshawe, ‘getting religion’ and going into the priesthood. However, his induction to the faith was short-lived, and Symons broke away to focus on his own personal interpretation of Catholicism through painting. Biographical detail on the artist is as scant as his painted legacy, which may account for his obscurity today. Much of his surviving work is owned by the council of his home town, Reading. But anyone heading to Edinburgh this summer will have a good opportunity to see more of it: one of his canvases features in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s current exhibition of British interwar realism (until 29 October).