As an exhibition of new paintings opens across two venues in the US, Christopher Le Brun PRA talks to Thomas Marks about the musical and mythological inspirations behind his work

Your upcoming exhibition has the title ‘Composer’. What correspondences do you perceive between musical composition and the process of painting?

Very early on, when I first started listening to music, I realised that there were particular correspondences in the sense of structure. I even borrowed a score of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande from the central library in Portsmouth because I just wanted to see what it looked like; I could imagine images but I wanted to see how it all came about.

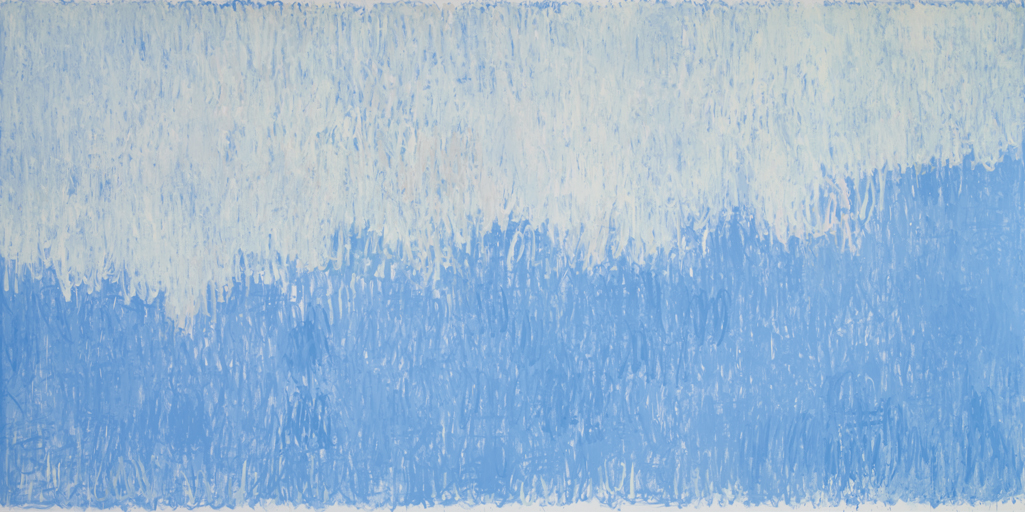

Although I can’t read music, I find it fascinating to see the strange correspondence between a notation and the sound. That struck me as having a relatively straightforward connection to what I was thinking about as an artist. In the exhibition in New York there’s a painting called Strand. When I was just 17 I did a small watercolour study for an imaginary large painting, and it looks like this painting that I’ve just done – so something about music I think, even from that young age, has persisted with me and in a way is only now starting to play out.

When you listen to music, you feel the rhythm, you feel the presence of the music, but you also very powerfully feel the spatiality – particularly in the music that interests me, which is from the early 20th century. Then you feel out these structures with your mind. That seems to me to have a correspondence with painting, where you’re feeling for and sensing structures and forms of space.

Is there something of the notation of music in some of the vertical marks in these paintings?

Take an idea like a chord: it’s a fairly straightforward comparison to come up with a grouping in its verticality. Things obviously operate very differently in a painting, but I’m not unhappy if that becomes analogous in the way that you look at it. Of course, my work has included trees, stems, branches, all of these relatively abstract vertical components.

Do you listen to music while you are painting?

Yes, but not always and it’s absolutely not a direct response. No, that’s not the relationship, not at all. In fact, if anything I may use music to switch off. There’s one painting called Pelléas, and that stands as an attempt to encapsulate my ideas about an opera that I’ve been thinking about for more than 40 years. The connection is never straightforward.

In the catalogue, you describe painting as ‘a questioning form’. What types of questions do these paintings ask?

Painting is essentially about appearances. The only way to encounter appearances is by looking. Can you hear in the word ‘looking’, how it’s a question? It’s not seeing, it’s looking. Looking immediately engages you in a questioning or wondering way.

A painting can be used to carry messages and it can illustrate stories, and the bulk of paintings historically are illustrative of stories, but the type of painting that holds me contains, as it were, innocent questions about the world. Why is there appearance at all? Why do things look like this?

Does your work retain the interest in the mythological that characterised it in a more figurative stage? If so, how does that now manifest itself?

Yes, it does. I remember as a student, one of my teachers used to say to me, ‘Christopher, the quest, remember it’s a metaphor,’ because I always misinterpreted, thinking the metaphor was the real thing – and I suppose I’m still susceptible to that. The metaphoric aspect of painting is very powerful for me. Now I paint to re-enact myths rather than picturing them.

One type of interpretative framework for these abstract works is their titles, which range from enigmatic pronouns or adjectives to a snatch from Ezra Pound. How important is the act of titling each painting?

It’s extremely important because you can smother a painting with the wrong title, but the right one can bring it to a more subtle life. Take the case of Strand, which is the painting that had this forerunner early drawing – just after that I started reading Ezra Pound. There’s a translation by Pound, a little phrase by a troubadour poet, maybe Arnaut Daniel, something about the sun raining light, and he says, ‘Thus the light rains, thus pours,’ which to me described the vertical marks of falling light, not rain but falling light. I’ve never forgotten it.

You worked on these paintings while the Royal Academy’s ‘Abstract Expressionism’ exhibition was coming together, and finished some of them as it went on display. How has that movement influenced your own painting?

I can illustrate a particular moment, which was the first time I encountered Philip Guston. But I didn’t encounter him through the look of the painting. I heard a tape of a radio interview he did with David Sylvester, so all I heard was two men talking about painting, and I was completely gripped by it. I remember it clearly because what Guston was talking about was painting as a means of thinking, or thinking as a means of painting.

That was an important moment for me. It left behind the notion that the artist thinks up a picture – I use the word ‘picture’ deliberately – and then carries it out in the form of a painting. What Guston is doing, and what the great Abstract Expressionists are doing, is thinking, living, painting all at the same time with anxiety and doubt as their material rather than their problem.

My work has had this continual dialogue with those artists for many, many years. I believe that in many ways Abstract Expressionism was one of the last primary events in painting.

What I and other artists did in the 1980s was also primary in a sense, because we then overlaid the achievement of Abstract Expressionism with the possibility of figurative risk. In Germany, the clear analogy is Baselitz. His move of terrific conceptual economy was just to invert the figure, and that’s not something I was prepared to do. I preferred to hold on to the picture problem in painting.

Your role as President of the Royal Academy carries many responsibilities and duties. But has the post altered your attitude to your own painting?

One side is practical, and the other side is semantic. That may sound a bit pretentious but I’m trying to describe it accurately. On the practical side, it intensifies my work because I give three days to the Academy and I give the rest of the week to my studio, so my suit and tie come off and my jeans come on and I’m in here working, and I have an absolute distinction between the two things.

On the other side, the presidency has a symbolic role, which connects me directly back to Joshua Reynolds. This isn’t about me, it’s about the presidency, what it means. And for someone to whom history is very vivid, it raises the stakes because the whole position of the Royal Academy and the presidency is an imaginative act that in our curious English way we’ve embedded in the middle of society. We’ve put a group of creative people whose lives are led by their imaginations into a central public position. This is completely glorious.

And finally – to refer back to your 2015 woodcut series, Seria Ludo – do you still feel a sense of play when you paint?

There are several words that one uses with extreme caution: pleasure, joy, the ecstatic… Joy has to be part of the vocabulary of art. In fact, isn’t it part of our duty as artists, our responsibility in a way to bring out the pleasure of art? Someone came to the studio the other day and said very tentatively, ‘There’s a lot of joy in these paintings’. There’s always the risk of thinking that’s a bit second rate. But is it?

‘Composer’ is at the Gallery at Windsor, Vero Beach, Florida (27 February–27 April) and Albertz Benda, New York (2 March–15 April).

From the March 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.