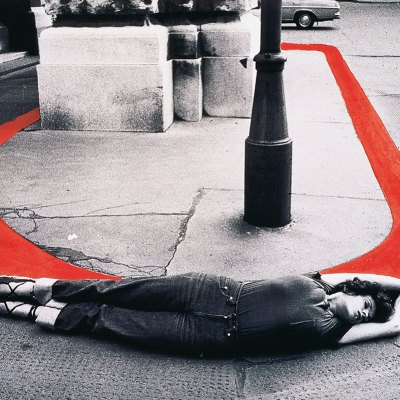

Still from Mirror Talk (detail, 2024) by Julie Rrap at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Photo: courtesy the artist; Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne; © the artist

Still from Mirror Talk (detail, 2024) by Julie Rrap at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Photo: courtesy the artist; Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne; © the artist

The Australian artist Julie Rrap has been thinking about representations of women’s bodies for more than four decades. Now in her seventies, Rrap has turned to making work about her earlier selves, ageing and the lack of older women’s bodies in art and culture. ‘Past Continuous’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney offers a tightly curated look at then and now, setting Rrap’s latest work alongside her famous early photo installation Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (1982).

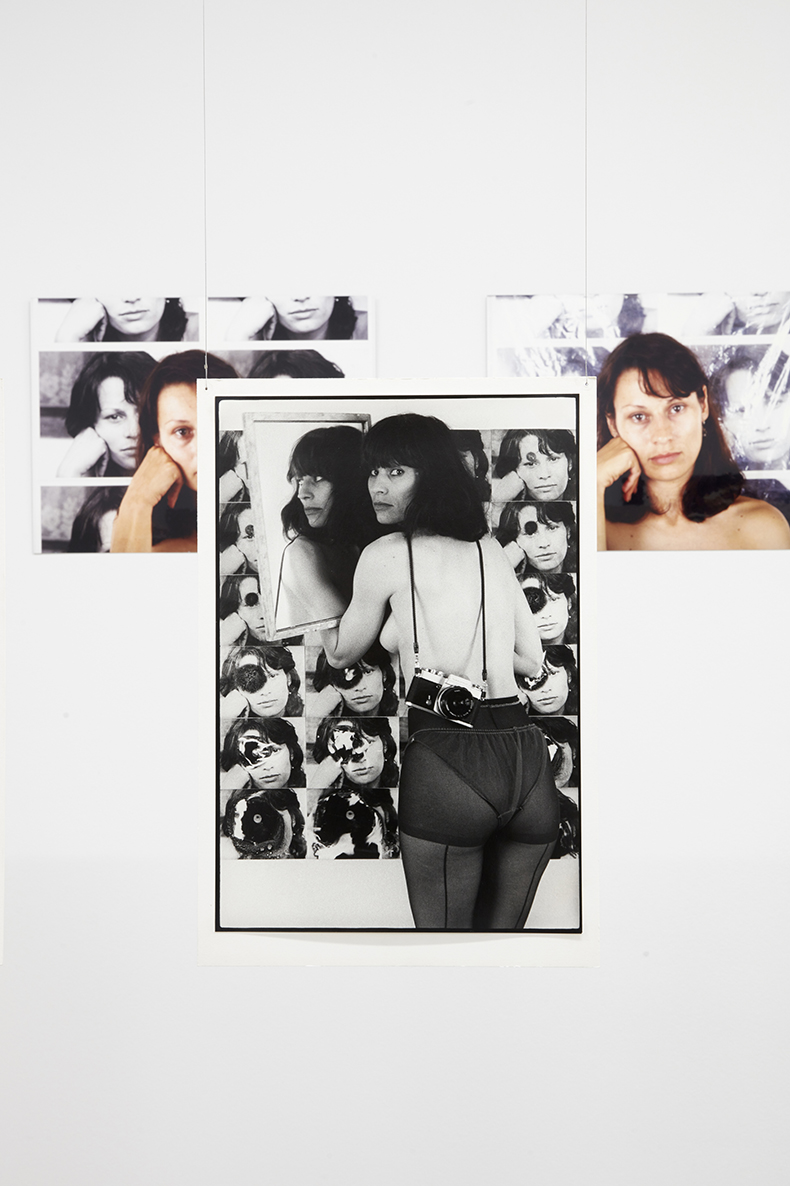

Disclosures is a key work in Australian feminist art and for good reason. The playful and engaging work documents Rrap in her studio, performing and inverting the roles of subject and object. There are more than 70 photographs. Some show Rrap posing with a mirror or her own self portraits. Others offer her view of the studio. These opposing perspectives are also carried into the installation itself, with works suspended from the ceiling in facing rows. Gaps allow glimpses of the works behind. Right from the very start then, Rrap has been working with mirrors and doubles – and often doing so with a sense of humour.

Installation view of Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (detail; 1982) by Julie Rrap at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Photo: Zan Wimberley; courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia; © the artist

Rrap’s work now ranges over many mediums but her approach has not changed. ‘Past Continuous’ opens with a new, large-scale bronze sculpture, SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders) (2024). The piece is a major undertaking, commissioned by the Melbourne Art Foundation and, just like it says on the tin, shows Rrap literally balancing on her own shoulders. The work is made from two life-size casts and almost reaches the gallery ceiling.

‘If I have seen further,’ Isaac Newton once said, ‘It is by standing on the shoulders of giants.’ It’s easy to understand why a feminist artist who started out in the mid 1970s might want to ask, where are my giants? SOMOS captures a sense of Rrap’s resilience and persistence, but it also displays a sharp awareness of the kinds of nudes that are prevalent throughout Western art history, and of how little we see older women’s bodies in art and culture. These days, there’s a wider cultural conversation going on about invisibility – a term also repeated in the exhibition’s curatorial statement. The euphemism makes the devaluation of older women sound gentle, as if they just helplessly fade away, but the term is ultimately about disgust. Here, Rrap’s frank representation of her body is a welcome antidote, but it’s not the novelty of her subject matter that makes SOMOS so interesting. As with much of Rrap’s work, it presents bodies in action. Here, the two Rraps are posed in expressions of concentration and inward focus, utterly consumed by the task at hand. They are women at work.

Installation view of SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders) (2024) by Julie Rrap at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Photo: Zan Wimberley; courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia; © the artist

Rrap uses her own body in a similar way in Drawn In (2024), a three-channel video work that documents her attempts to draw the outlines of her body. There are some small missteps with the install here. The accompanying wall print is so big that Rrap’s outlines of her hands are comically giant. Still, the video is undeniably powerful: Rrap moves quickly, the cameras are all on her person, and the shots are of limbs and flesh. The lines on the paper build incomplete, overlapping palimpsests. It’s a work where it’s impossible to see the whole of anything.

In another new video work, Mirror Talk (2024), Rrap places an old and current self portrait side by side. The features of each woman are progressively tweaked and made strange, as lines from Sylvia Plath’s ‘Mirror’ roll beneath. Plath’s poem is about looking at her own reflection in the mirror, ‘searching my reaches’, but here it comes to speak about the act of looking at photographs across time and trying to make sense of earlier selves. Time Passing Through Me (2024) also uses old photographs. This video piece incorporates self-portraits from Rrap’s early Disclosures series. The body begins to ripple and shift, and occasionally reveal the present-day artist too. We never step into the same river twice, as the saying goes.

The MCA held a major retrospective of Rrap’s work in 2007 and ‘Past Continuous’ is clearly intended as a kind of postscript. It’s a small exhibition and the focus is on creating a context for more recent work rather than following every avenue of her career. Yet asking audiences to applaud works such as SOMOS inevitably raises the spectre of invisibility too. What does it mean for this major institution to celebrate this established artist again? What of other, less prominent artists? Or other kinds of ‘invisible’ bodies? Still, ‘Past Continuous’ is a powerful exploration of the questions that drive Rrap as an artist. Throughout her career, she has used her own body to explore the dynamics between subject and object, and to push at the limits of representation. Identities are always moving. In her new works, Rrap’s reflections on ageing introduce even more layers and doubles, though perhaps it’s the video work Drawn In that offers the most here. The soundtrack echoes throughout the gallery. The steady thump of Rrap’s limbs and the scrape of her charcoal on the paper infuse the space with energy and vitality. There is still so much to be done.

‘Julie Rrap: Past Continuous’ is at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until 16 February 2025.