From the May 2020 issue of Apollo

Like almost everything at the moment, my meeting with Julio Le Parc takes place online. On my screen the 91-year-old artist appears – just as he does in most portraits – clad in his trademark blue lab coat with an orange collar, a stack of pens and a compass in its front pocket. The clip-on shades of his glasses cast a slight shadow across his face, but I can see that he is smiling, evidently quite amused by this novel set-up. We speak in French – the second language of the Argentine artist, who moved to Paris in 1958 and since 1970 has lived in the suburb of Cachan, just outside the capital. It is here, in late March, that he is now sequestered as a result of the coronavirus lockdown, and which has also meant that the exhibition we are supposed to be discussing, a survey of new and historic work that was supposed to open in April at Perrotin in New York, has been postponed until at least the autumn.

Still, Le Parc continues to work (‘today, yesterday, the day before’) in the large, light-filled atelier that adjoins his family quarters. One of Le Parc’s assistants, Eduardo Berrelleza, has already given me a live video tour of this space. It’s practically a museum, offering a comprehensive survey of the artist’s six decades of experiments with colour, movement, light, space and perception. Blue and red mobiles, made up of hundreds of tiny squares of Plexiglas strung together with nylon thread, hang from the ceilings like disco balls. On the walls and stacked on shelves are the paintings, similarly joyful profusions of abstract forms – circles, squares, lines that curve and make loops, sometimes across multiple panels. On the tables there are sheets of paper: sketches annotated with words and figures, precisely planned maps to future projects. I ask Le Parc what he is working on right now. ‘Different things,’ he says, and then holds up a roughly A3-sized colour print-out of a familiar image: a grey sphere flecked with spongey red spikes and dots of orange and yellow. It’s a picture of the new strain of coronavirus, created earlier this year by medical illustrators at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Is he making some kind of sculpture? ‘No, a little video. Later, if it’s good, I’ll send it to you.’ Berrelleza assures me that this is not a joke; for the past two days, Le Parc has been working on a film based on the illustration – not a medium he is known for. Then again, Le Parc has never been afraid of venturing in uncharted directions; he describes himself to me as an ‘experimentalist’.

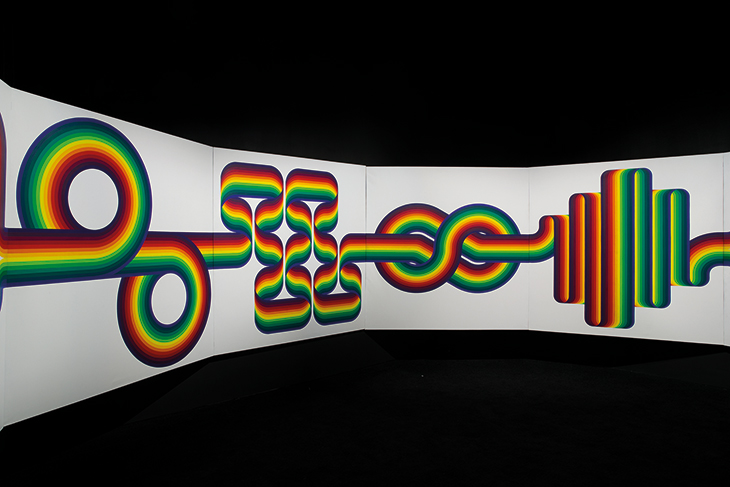

Alchimie 338 – Spirale des Carrés Sept Couleurs (2008–16), Julio Le Parc. Photo: Claire Dorn; courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

Born in 1928 to a working-class family in Mendoza, a city at the foothills of the Andes, Le Parc started working – as a newspaper delivery boy, at a crate-making factory – at the age of 13. The following year he moved with his mother and siblings to Buenos Aires where, after day shifts as an apprentice at a leather-goods factory, he took night classes in preparation for the entrance exams to the Escuela Preparatoria de Bellas Artes. He had no aspiration to be an artist at this point, he tells me via email a few days after we have spoken. But ‘As soon as they put an easel in front of me and I grabbed some charcoal and paper to draw a model, I realised that was what I liked doing.’ He was accepted to the school, whose teachers included Lucio Fontana, recently returned from Italy and developing the ideas about time and space that would feed into his Spazialismo movement. Spazialismo, along with the Concrete art movement that also emerged in the mid 1940s, had a strong influence on Le Parc – as did the politically charged atmosphere at the schools, where there were continual strikes and protests against the repressive regime of Juan Perón, elected as president in 1946. At one point, in what he has previously described as a fit of ‘confused’ teenaged rebellion, Le Parc quit his studies and went hitchhiking across Argentina, ‘liv[ing] a bit on the margins […] hanging out with anarchists and Marxists’. Eventually he returned to school (now the Escuela Superior de Bellas Artes), where he threw himself into student organising, a role that earned him a reputation among school officials as a troublemaker.

To Le Parc’s surprise he was granted a scholarship to travel to Paris in the autumn of 1958, which he designates as a sort of ‘Year Zero’ in his life as an artist. A major impetus for this journey was his encounter earlier that year with the work of the great Op art pioneer Victor Vasarely, in a solo exhibition at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires. The French-Hungarian artist presented a series of recent monochromatic works that had ‘a very strong visual impact’ on Le Parc. Within a few months of his arrival in France, Le Parc was joined by his partner (and later wife) Martha as well as other artists from his circle in Buenos Aires: Horacio García Rossi, Francisco Sobrino, Hugo Demarco. Both together and separately the men made visits to Vasarely’s studio, where in his dizzying canvases they felt they had found a pathway that diverged from dominant trends. ‘The analysis that I made and shared with the members of the group,’ Le Parc says, ‘was that the contemporary creation at that time was very elitist, very closed, adhered very strictly to what prevailed at the time: tachism, lyrical abstraction, Art Informel […] Within that whole panorama, the [role of the] spectator was completely absent, so we realised that this was a major theme.’

Rotación Translativa (1959), Julio Le Parc. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

The first works that Le Parc created in Paris – which even in the traditional medium of painting he describes as ‘experiences’ – were in black and white, and then also grey: precisely ordered gridded or linear arrangements of geometric shapes on cardboard and canvas. For Le Parc, the systems that governed these compositions were fundamental – a way of limiting the artist’s expressive role and creating as direct a relationship as possible between the artwork and the viewer. Gradually, he began to allow colour into the frame, progressively building up his palette: ‘I wanted to see what would happen if instead of using a small monochromatic range, I used a complete range like the rainbow, which starts with a colour, goes around and comes back to the same colour: yellow, green, blue, purple, red, orange and then yellow again […]. First with six colours, then 10, and then 12 and in the end I stuck with a range of 14 colours that enabled me to create more permutations.’ Since 1959, these 14 colours (along with black, grey and white) are the only shades that have appeared in Le Parc’s work. During my tour of the studio, Berrelleza shows me a colour chart on which each shade of paint is numbered from 1–14 and labelled with the name and number assigned by its manufacturers. One of these has recently been discontinued, so the studio is going to have to find a way to produce it in-house.

Série 14 E n °12 (1972), Julio Le Parc. Photo: Claire Dorn; courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

For an artist so concerned with systematisation and the fixing of parameters, Le Parc’s body of work is also deeply varied. In 1961 he cofounded the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) – a rebranding of the Centre de Recherche d’Art Visuel, formed the previous year – together with García Rossi, Sobrino, Demarco, and the French artists François Morellet, Joël Stein and Jean-Pierre Yvaral. In the decade that followed, whether working alone or as part of GRAV, Le Parc experimented with light and kinetic sculpture, installation and participatory art, while also writing texts exploring the theories that governed his approach – and made sense of all the variety. I ask him if there is one piece of writing that best encapsulates his thinking. ‘There was one I wrote by myself in the early ’60s – I tried to get it signed by GRAV, but it wasn’t possible.’ Berrelleza digs out the title for me later: ‘À propos de: Art-spectacle, spectateur-actif, instabilité et programmation dans l’art visuel’ (September 1962). The text is a challenging, highly theoretical read, in which Le Parc makes the case for artworks ‘that are made in the process of one’s looking at them’ and which ‘manifest instability in its most abstract form’. But it also relates clearly to his work of the time, particularly his series of ‘Continuels-Mobils’, the arrangements of plastic squares suspended with nylon thread, sometimes incorporating lights and motors, as well as his light-based ‘Continuels-Lumières’, which all make literal the notion of an unstable, constantly shifting work of art – and can be breathtakingly beautiful to look at.

Julio Le Parc at the XXXIII Venice Biennale, 1966. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

The installations and live events push Le Parc’s ideas even further. In 1963 at the Paris Biennale GRAV presented L’instabilité: Le labyrinthe, the first in a series of maze-like installations filled with different kinds of work: mobiles and kaleidoscopes, contorting mirrors, interactive games. Later, Le Parc would also create his own ‘Salles de Jeux’, equipped with things like ping-pong bats and balls and punching bags imprinted with the images of figures including ‘the artist’ and ‘the priest’. Since the 1990s, with the rise of a new generation of artists such as Carsten Höller and Olafur Eliasson who are interested in art as a participatory experience (what is sometimes called ‘relational aesthetics’), the influence of these earlier works has become increasingly clear. Some critics have been sceptical of the ‘fun-house’ approach, deeming it silly and superficial. But for Le Parc, nothing is ever just a game: he sees the ludic dimension as essential in encouraging the spectator to engage actively and critically with the work. This in turn, Le Parc has argued in the past, can have wider political implications: ‘If people on a low income, who occupy a subordinate position in terms of social life, work and family, can recover a bit of energy and optimism by visiting an exhibition […] they might be able to proceed in a different way in a different aspect of their lives with that acquired energy.’ He still has faith in this possibility, he tells me. ‘The problem is,’ however, ‘that contemporary art, in order to survive, is usually limited to viewers who are on the “circuit”, and to the arbitrators of value within the art world […] that is, critics, galleries, collectors.’ It was this same concern that in 1966 led GRAV to leave the gallery and step into the streets with Une Journée dans la Rue: a day-long project dispersed across sites throughout Paris, where passers-by were invited to sample a range of experiences – springing seats, distorting glasses – and fill out a questionnaire gauging their responses.

Photograph documenting Une journée dans la rue: dalles mobiles (A Day in the Street: moveable tiles), Montparnasse, Paris, 19 April 1966. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

Also in 1966 Le Parc was awarded the grand prize for painting at the Venice Biennale, where he had shown around 40 works in different mediums. Suddenly, galleries were taking an interest; he got his first solo show in Paris at Denise René that same year. All this attention began to overshadow the work of GRAV. And then there were the events of May 1968 – a collective uprising that seemed to suggest their work had grown obsolete. The people had been politically activated, their energies stoked. ‘I think that what we proposed was more or less confirmed by the May ’68 movement, both at the level of students and at the level of industry, of workers, of employees, of institutions, of strikes. The idea we’d been planning before […] of doing a tour in the style of Une Journée dans la Rue and taking it all around France… that was no longer necessary.’ Le Parc, meanwhile, found himself expelled (along with Demarco and others) from France for five months after being arrested for supporting the occupation of the Renault factory in Flins. Shortly after his return to Paris, which was thanks to a campaign waged by his friends and associates, GRAV signed and issued an ‘Acte de Dissolution’.

Modulation TD n °69 (1976), Julio Le Parc. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

After his expulsion – and the decision he took, on the basis of a coin toss, to decline a solo exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne in 1972 – Le Parc found that he had become ‘a bit of an enemy’ in the eyes of the cultural gatekeepers in Paris. ‘So for decades I was like a little pest they had to brush aside, and was forgotten, and relegated and practically disappeared, but that didn’t stop me from exhibiting everywhere, throughout the rest of Europe and Latin America.’ He became involved in collective projects, with other Latin American artists or with international anti-fascist brigades, in solidarity with liberation movements in countries with oppressive and dictatorial systems: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chile and elsewhere. All the while, Le Parc continued to produce his paintings and sculptures exploring the relationships between colour and form, from his new base in Cachan – notably with his Modulations series (1974–ongoing) and then with another painting series titled Alchimies, which he began in 1988 and is also ongoing. For these, he devised new methods of applying paint with airbrushes and spray guns that allowed him to create subtle gradations of colour and tone, resulting in illusionistic images of familiar motifs: round balls, cylindrical tubes, curving sheets. The latter series also incorporates quasi-pointillist streams and clusters of multi-coloured, closely spaced dots, evoking the immaterial properties of light and movement. He worked on discrete projects, too – such as La Longue Marche (1974), a monumental ten-panel set of white square canvases adorned with rainbow-striped ribbons that unfurl across more that 65 feet, which he has described as ‘a happy metaphor’ for the condition of being human: a long, wearying journey, fuelled by sheer persistence and leavened by optimism.

Installation view of La Longue Marche (detail; 1974) by Julio Le Parc in the Unlimited section at Art Basel, 2017. Photo: Claire Dorn; courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Julio Le Parc/ADAGP, Paris 2020

In the past decade institutional interest in Le Parc’s work has picked up again. Since 2014, he has had solo exhibitions at the Serpentine Galleries in London, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, the Met Breuer in New York and – just last year – at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes and CKK, both in Buenos Aires. He has not been content simply to ride this wave, or to limit himself to his existing range of materials. In 2017 he collaborated with his son Juan Le Parc on Alchimie Virtuel, his first piece using virtual reality (VR) technology. The work seeks to place the viewer ‘inside the painting’ – a culmination, one could argue, of his longstanding quest to create a fully immersive aesthetic experience. This was also a somewhat surprising move, given Le Parc’s insistence that he is not really interested in technology. ‘I always rejected the idea that because I used a motor or light, my art could be classified as “technological art”. Even the more advanced techniques I use nowadays, like virtual reality or mapping – I don’t think they are what define my work. They are techniques which can be useful to me and can help me to achieve certain results.’

Still, I want to know where this drive, to continue developing new techniques and conduct further experiments with them, comes from. In the short term at least, Le Parc’s studio is without its usual occupants (he has a team of some 12 assistants) but he is nevertheless revising plans for the upcoming exhibition at Perrotin, while also devising an online display to be shown by the gallery in the meantime. ‘I still have many projects yet to do,’ Le Parc says. ‘In any creative process, new ideas and new creations keep appearing, new little paths I follow, to carry on exploring.’

Julio Le Parc, photographed in his studio in Cachan in February 2020 by Claire Dorn

‘Julio Le Parc: In the Studio with Julio’ is available to view on the Perrotin website until 5 July.

From the May 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.