In Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, published to justified acclaim last year, there’s a short, stark stanza written in memory of the many unarmed black men such as Eric Garner and Michael Brown who have been killed by US police officers in recent years:

because white men can’t

police their imagination

black men are dying

It’s a line that emphasises racism’s relationship with fantasy and myth, and how the internalisation of stereotypes can have violent, deadly consequences.

Rankine’s poetry, especially that doubled-edged phrase ‘police their imagination’, feels particularly pertinent to Kara Walker’s new exhibition at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London. The show is filled with references to contemporary race relations in America, and one of the first works on display is a small, poignant drawing on graph paper entitled An Unarmed Black Man. Yet, Walker’s new work is certainly not a sombre or restrained memorial to lives lost. Rather, it gives full expression to wild fantasies concerning racial stereotypes and American history. In fact, we might call it a show about unpoliced imaginations.

Four Idioms on Negro Art #2 Graffiti (2015), Kara Walker. Courtesy the Artist, Sikkema Jenkins & Co. New York and Victoria Miro, London © Kara Walker

These fantasies centre on the black body, which Walker exposes as a site for diverse fears and desires, speculations that intertwine sex, violence, death and the legacies of slavery. One large watercolour shows a moonlit orgy – or is it a rape? – featuring a cop in full riot gear wielding his baton with a skull under his boot. Another work in the same series places naked pole-dancing black women amidst police guns and protesting figures, a murky scene perhaps inspired by the tear-gas clashes that took place in Ferguson, Missouri last summer.

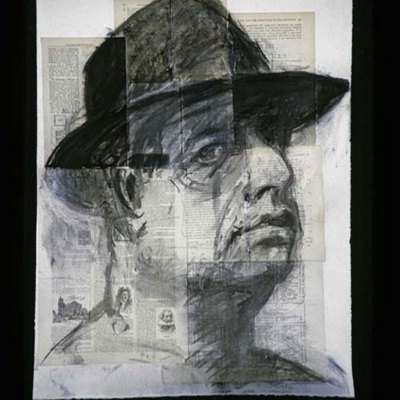

Walker’s privileging of a cartoonish style containing racial caricatures, with particular nods to folk art, graffiti and primitivism, is designed to draw attention to how forms of representation are linked with wider social assumptions. Her own position in the debate remains ambiguous, however. On a list of dichotomies sketched on paper – which posit an educated and masculine notion of conceptual art against a lower class, unskilled and feminine aesthetic – Walker notes, ‘That’s me!’ next to both inventories.

‘Kara Walker | Go to Hell or Atlanta, Whichever Comes First’ installation view at Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Kara Walker

Upstairs at the Victoria Miro, there’s a more sustained focus on history and memory. Dominating the far end of the gallery is an extraordinary photographic wallpaper piece, completed in collaboration with Ari Marcopoulos, depicting Stone Mountain in Georgia. Stone Mountain is an enormous granite monolith and carved into its side is the largest bas relief sculpture in the world – ‘a grand, hubristic, fascist enterprise’, according to Walker (who lived near it as a teenager), featuring two Confederate Generals alongside Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States during the American Civil War. The site has been controversial for many years, not least because it served as a rallying point for the Ku Klux Klan, though the inevitable theme park now present – a true Dismaland – is keener to promote pumpkin festivals and laser shows than mention the contested memories evoked by the sculpture. By contrast, Walker and Marcopoulos’s massive reproduction of the mountain stresses the size of the related historical issues, as well as the scale of racial conflict still evident in American society today.

In a series of small pencil drawings and watercolours adjacent to the wallpaper, Walker reimagines Stone Mountain. In some instances, she blots out the Confederate sculpture, as if attempting to erase the history that underpins it; in others, she makes it a more explicit site for white supremacist fantasies by adding giant burning crosses, racist slogans and a memorial to Dylann Roof (the alleged murderer of nine African-Americans in a South Carolina church in June).

The Jubilant Martyrs of Obsolescence and Ruin (2015), Kara Walker. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Kara Walker

More historical fantasies can be seen on the other side of the room in The Jubilant Martyrs of Obsolescence and Ruin, a stunning example of Walker’s characteristic silhouette narratives in cut-out paper that unfolds across the length of the gallery wall. It’s a grotesque story full of swords and saws, bucking horses and severed heads, all played out by characters straight out of a cartoon version of the Civil War.

Walker’s cut-outs also provoke comparison with the silhouettes and assorted itinerants travelling around the incredible eight-screen projection by William Kentridge, More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015) – the highlight of his current show at the Marian Goodman Gallery in London. In the powerful new work of both artists, hellish and farcical scenarios are filled with energy and animation – indicating, perhaps, a refusal to police either historical memories or their own imaginations.

‘Kara Walker: Go to Hell or Atlanta, Whichever Comes First’ is at the Victoria Miro Gallery until 7 November 2015.