From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It’s fair to say that obsession is not exactly a rare trait among art collectors. What is rarer is to have collected as intensively, as widely, and in such prolific quantities as Karun Thakar: a full-time collector who has devoted himself to acquiring, conserving and exhibiting objects that range from Delft pottery plates to Tibetan painted chests. Depending on the classification of items, these number in the tens or hundreds of thousands. (Is a single Venetian trade bead, exchanged for enslaved people from West Africa in the 1500s, an individual piece – or is that the necklace on which it was later strung?)

Ashante gold ring with a design of beehives and hummingbirds, 19th century, Ghana. Photo: Desmond Brambley; © Karun Thakar Collection

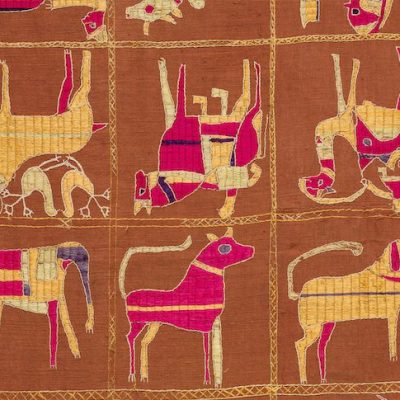

The largest proportion of Thakar’s collection is, however, made up of antique textiles. It is one of the most important of its kind in private hands. It is a collection defined by its eclecticism, including as it does Japanese boro textiles and kimonos, Indian chintzes, Ghanaian asafo flags, English smocks, embroidered Afghan costumes and more; the greatest number are from Asia and Africa. What, I ask him, is the thread connecting these apparently disparate areas of interest? ‘I see them as overlooked collections, made up of things that people have not traditionally collected – art that is seen as “folk”. They were made by ordinary working people, often by women,’ Thakar says. ‘Such objects have always attracted me.’

A corner of the living room with albino turtle shells, a painted temple hanging from Maharashtra, c. 1800, and a pair of 18th-century painted wooden heads from a temple in Gujarat. Photo: Ellen Christina Hancock

His very first acquisition, at the age of 10, was a tiny bronze statuette of Ganesh, purchased at a Delhi market, with pocket money. This piece now lives in the English dowerhouse-turned-inn that Thakar and his partner call home, where it is surrounded by dozens of other Indian folk bronzes. With so many and varied interests, why the focus on textiles? ‘To me, textiles are unique compared with any other art form, because we always have them touching our bodies. The garments I collect all have a human patina.’ It’s not hard to find a biographical explanation here. Thakar’s mother ran a tailoring business in Delhi, where he learnt to embroider, crochet and knit. ‘I suppose that stayed with me,’ he says. ‘I recently spent seven months repairing a French worker’s jacket with boro patches; I find it quite soothing.’ His house contains rails upon rails of folk dress from across the world – from embroidered Afghani veils, to kimonos of meisen silk that combine Western patterns with Japanese design. Thakar’s extensive collection of meisen kimonos, made with a weaving and dyeing technique popular in the early 20th century, is the subject of a book by the keeper of the V&A’s Asian Department, Anna Jackson, published in 2015.

The size of his collection – which he shares with the public through exhibitions, museum loans, books, a website and a popular Instagram account – might suggest that this is a well-staffed affair. The Karun Thakar Collection is, in fact, a one-man band, barring a few weeks’ assistance in the run-up to exhibitions. ‘People write to me saying, “Please could you put me in touch with the curatorial team?” Really, it’s just me,’ he says. ‘It’s a huge responsibility, especially when you’re caring for things like seventh-century Sogdian silks. And it’s just constant.’ Thakar has had a varied career that includes running a retirement home, monitoring racist attacks for a law centre and working in HIV/AIDS prevention among Black and Asian communities, but after the death of his brother in 1996, he turned to studying: first on an art foundation course, then on a fine art degree. He has devoted himself to collecting ever since.

Clothing rails filled with Mangala dresses made by the Pashtun tribe of Afghanistan and antique Turkoman coats of embroidered silk. Photo: Ellen Christina Hancock

Clothing racks and boxes of folded textiles fill a warren of attics in his home. Living rooms, bedrooms, guest rooms and studies brim with art; the basement is for conservation. Not for him the paranoid sterility of perpetual storage – Thakar lives surrounded by objects. I am astonished to hear that he does not keep an inventory. The knowledge of what an object is, where it came from, and where it is now is all held solely in his head. This caused consternation among a visiting group of National Trust curators who implored him to start making records. ‘I must have 10,000 objects photographed, but that’s not even scratching the surface,’ he says. The inventory will have to wait.

This summer, the boro jacket Thakar mended appeared in his exhibition ‘Japanese Aesthetics of Recycling’ at the Brunei Gallery in the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London. The show featured boro (‘mended’) textiles, including kimonos made from old tengui (hand towels), and noren (room-dividing curtains) patched together from advertising banners. It also included yobi-tsugi pottery pieced together from shards and kintsugi-repaired ceramics dating from the 10th to 19th centuries. In one remarkable example, a chunk missing from a grey-green dish is replaced by a vivid slice of red lacquer. The exhibition also included items made from washi paper: old ledgers repurposed to make storage bags, floor coverings and room dividers, or turned into shifu garments, woven from twisted and plaited paper yarn. These are humble objects, originally worn by fishermen or farmers. In both their aesthetic and the make-do-and-mend values they represent, these objects have a very contemporary appeal.

Earthenware jugs in the basement workroom, created over a 40-year period by Peter Smith (b. 1941), with a vessel below by Jason Wason (b. 1946). Photo: Ellen Christina Hancock

‘Japanese Aesthetics of Recycling’ was the latest in a series of shows at the SOAS gallery. Each aims to introduce the public to underexplored areas of textile history through Thakar’s collection. ‘These pieces often tell the stories of women,’ he tells me. ‘In the baghs show [‘Embroidered Gardens of Punjab: Baghs and Phulkaris’, 2021], there was a piece embroidered with the story of a married 16-year-old girl, murdered for having an affair with a priest. These stories are really important. Positions have shifted – both institutions and the public now want to see the art of the people, not just high art.’ The next exhibition at SOAS will likely focus on Afghan costume (‘All we hear about Afghanistan is linked with war – I’d like to introduce people to how amazing their embroidery is’), and there is a major exhibition on Indian chintz in the works. He is in discussion with several institutions for the latter; the V&A is keen to mount a joint show that pairs its holdings with Thakar’s, which is one of the largest private collections of chintz.

Chintz, the patterned cotton calico that emerged in Hyderabad in India and soon travelled to Europe, is a particular passion of Thakar’s. Historically, these patterns were woodblock-printed, painted, glazed or stained, usually on to a light-coloured ground. Such textiles became a favourite fabric among elites both in India and further afield. Thakar becomes voluble as we discuss chintz, giving a dizzying history of the trade in the material, taking in the various laws that governed its import, use and sale in European countries that feared its success would undermine homegrown industries. In 1717, Spain banned the import of calico – followed by a second ban in 1728 of the sale of European-made imitations. In Britain, the Calico Acts of 1700 and 1721 were similarly protectionist attempts to guard against India’s textile industry. The latter forbade ‘the Use and Warings in Apparel of imported chintz, and also its use or Wear in or about any Bed, Chair, Cushion or other Household furniture’. The first attested use of the adjective ‘chintzy’ was by George Eliot referring to cheap imitation chintz made in Britain. ‘“Chintzy” can be used in a very negative way – it’s often seen as grandmotherly. But fashion is cyclical,’ Thakar says. He’s not wrong: when designer Lulu Lytle and her company Soane Britain hit the headlines because of Boris and Carrie Johnson’s maximalist makeover of Downing Street, the press described the prime minister’s place as ‘a folksy, chintz-laden sinking ship’.

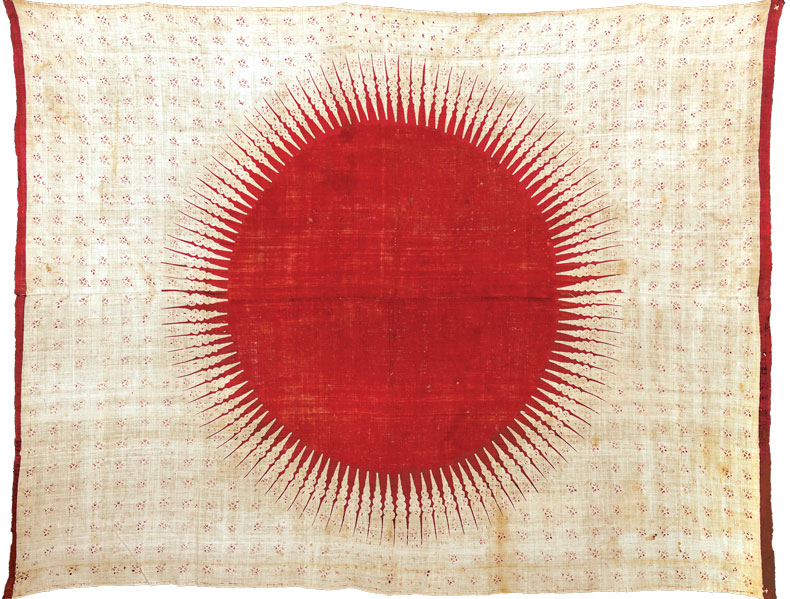

Ceremonial cloth with mata hari (‘eye of the day’) design, 18th or 19th century, Coromandel Coast, India. Photo: Desmond Brambley; © Karun Thakar Collection

Lytle is a long-term friend and collaborator, the only person Thakar has allowed to create new fabrics based on pieces from his collection. These include the chintzes, which have been reborn in patterns including ‘Coromandel Tulip’ – based on an early 18th-century sarong from the coast of south-east India, probably destined for Indonesian court use – and ‘Floral Lattice’, inspired by an 18th-century embroidered fabric, designed to appeal to the Western market. Though chintz is usually synonymous with fussy florals, examples in Thakar’s collection include more muscular designs. One example was the star of a recent exhibition at the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C.: an 18th-century ceremonial cloth bearing a radiating red sun, painted, resist- and mordant-dyed on the Coromandel coast for the Indonesian market. It’s a staggeringly beautiful design, which also graces the cover of Indian Cotton Textiles: Seven Centuries of Chintz From the Karun Thakar Collection (2015). This book is one of six he has worked on to date, each covering a different area of his collection. Number seven – out next year – is a collaboration with Stephen Ellcock, whose author bio describes him as ‘a renowned image-collector’. In contrast to Thakar’s more academic publications, the simply-titled The Book of Textiles will be focused instead on the formal qualities of the pieces.

As we speak, it’s impossible to ignore a magnificent painted textile hanging on the wall of his library: a 19th-century piece made in Ghana by Hausa painters, with a design of buildings and what Thakar calls ‘pseudo-Arabic’ religious text. He regards this work as ‘one of the most important to have survived [from the period]’. I’m lucky to see it: the precious textile is rarely on display. This outing is thanks to that recent visit by representatives of the National Trust. ‘It really needs to be in an institution – the Saudi museums want to buy it – but I’d like it to stay in London.’ This city, and British institutions such as the V&A and the National Trust, are close to Thakar’s heart.

The reasons for this are at least partly biographical. In his early teens, his family moved from Delhi to Nottingham – from a world of relative affluence and comfort to one of poverty and racist bullying. When he was 21, Thakar was assaulted by a group of skinheads, which required a period of sick leave. It was during this time that his then-partner began taking Thakar to National Trust properties. ‘People talk about how [National Trust properties] are inaccessible or whatever, but to me they’re safe havens,’ he says. ‘A few months later my mum found out I was gay, so the family didn’t want to know me. Comfort came from [visiting] those kinds of places.’ It’s unsurprising that he is now a passionate supporter of the charity. Thakar is talking to the National Trust about loaning objects for display at its properties. He is keen, for instance, to see rare 16th-century bed panels, made during the same period as furnishings bought by Bess of Hardwick, placed in Hardwick Hall.

To build such a collection, Thakar has made himself unpopular with dealers, he says, by going direct to the sources of their wares and offering London prices. ‘They say I ruined their businesses. But why should I give people overseas less than I would pay here?’ Much of his collection has been acquired directly in that way, in travels that have taken him across the world – Indonesia, Japan, West Africa, America, the Middle East – often travelling on a shoestring to save money for purchases. He is lucky to have bought items that were once unfashionable, but are now sought after. One case in point: six-foot-high African film posters painted on to 50kg flour sacks, which can today fetch tens of thousands of dollars. When Thakar was buying them, they were $50. The internet has changed his peripatetic habits. Contacts all over the world now Whatsapp him their wares instead. He cites Titi Halle of Cora Ginsburg gallery in New York and Francesca Galloway in London as two trusted dealers.

Though the collection is vast, Thakar is no jealous hoarder. He has donated items to several museums, including more than 100 to the V&A. In the United States, Washington’s Textile Museum has also benefited from his generosity. He has even made plans for the future of the collection after his death: it will be administered by a committee of friends. It matters to Thakar that the public life of these objects will continue after his stewardship ends. ‘It’s crucial to me that I share. I know people who just hide things, and only show them to so-called connoisseurs,’ he says. ‘I’m quite critical of these groups of elderly, mostly white men, just patting each other on the back.’

It’s precisely this desire to communicate beyond a rarefied circle – to foster a more expansive appreciation of these items and their histories – that led him in 2021 to establish the Karun Thakar Fund in collaboration with the V&A. From an annual budget of £40,000, the fund offers scholarships and project grants to researchers anywhere in the world who are working on Asian and African textiles and dress. Thakar has been delighted by the range of applicants; projects in Palestine, Ghana, Nigeria, Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States and India have all received funding. These projects are many and varied. ‘Some researchers from Eswatini, a tiny southern African nation, applied to study their national dress, and we’ve also funded a British college to buy Asian and African garments as study pieces – it took just £1,000 to make a difference there.’ He adds: ‘I’d love institutes with potentially bigger pots of money to use the fund as a model.’ If they do, the Karun Thakar Collection could have an afterlife even greater than the one its founder has already secured.

From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.