From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Kerry James Marshall’s retrospective at the Royal Academy presents the visitor with any number of surprises. Chief among them is the emphatically academic hang, in an arrangement that wouldn’t look out of place in the grander galleries of the Louvre or the Prado. It confronts us with mostly symmetrical arrangements of paintings, some immense in scale, smaller ones grouped in tidy batches, with little deviation from a form of display entirely foreign to contemporary painting. It also follows an almost entirely chronological course, addressing 11 major cycles of the artist’s work and swerving the ‘thematic’ mix-and-match strategy deployed in so many recent mid-career retrospectives. As if the point couldn’t be made any louder, it opens with a selection of paintings depicting studio settings and museum galleries much like the one we find ourselves in, filled with Black visitors; they’re grouped together under the title ‘The Academy’.

You’re left in no doubt that there’s an agenda here, one that follows the wider arc of Marshall’s career. His oeuvre, in the simplest of tellings, can be read as a monumental effort to assert the presence of the Black figure in the story of Western art, using painterly idioms taken from that canon. He has sustained this mission for four decades, in the process becoming the closest thing contemporary painting has to a canonical figure himself, and is deservedly seen as a godfather to a generation of African-American figurative painters who followed him.

Yet while his art can’t be completely dissociated from questions of race or art-historical reference, understanding it exclusively through those prisms seems reductive, if not downright daft. What that reading misses is the sheer oddness of Marshall’s vision, and the inventive visual gambits he deploys in order to mediate it.

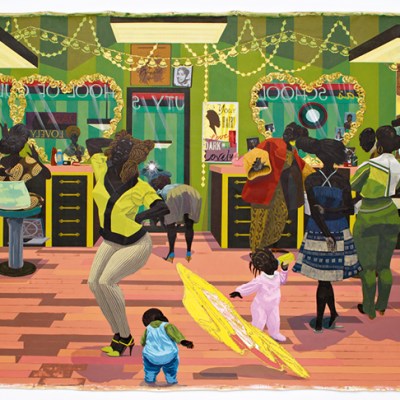

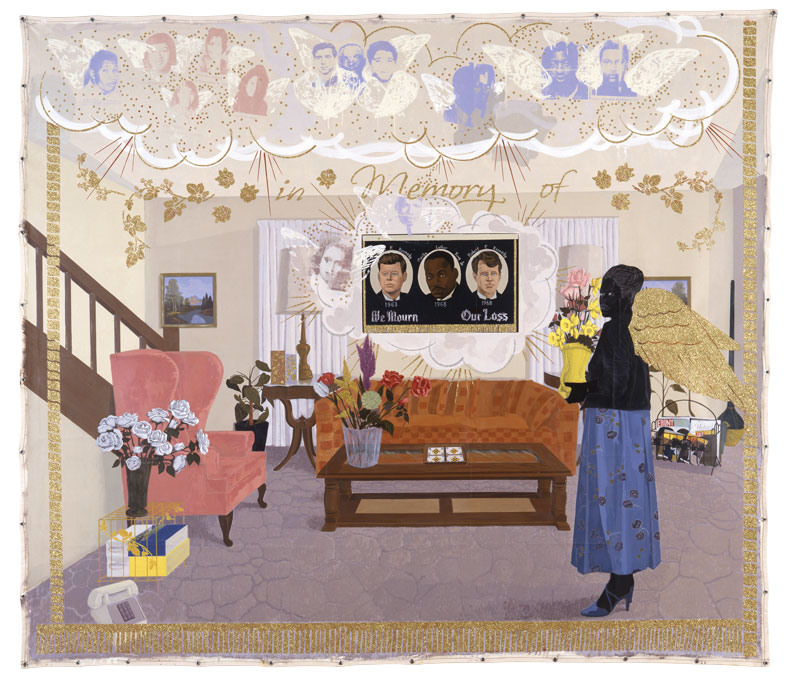

As the show’s title suggests, Marshall has a particular interest in the once-privileged genre of history painting, a mode he has been repurposing and occasionally subverting since at least the 1990s. The most arresting examples on display here explore grand historical narratives through microcosmic settings, rendering them on unstretched canvas at heroic scale. Consider the barbershop – an emblematic space of ‘sanctuary’ for the African-American community in Los Angeles – imagined in De Style (1993), in which a calendar hanging on the wall indicates the date of Rodney King’s beating at the hands of the LAPD; or the domestic scenes in the Souvenir series (1997), all of which are decorated with homages to deceased heroes of the Civil Rights movement – some diegetic (wall hangings with a distinctly home-made touch); some less anchored in realism, captured as clouds of text or screen-printed images hovering at the upper fringes of the pictorial space.

It could all come dangerously close to gimmickry – or worse, agitprop – were the artist less firmly wedded to keeping things interesting. Look at that barbershop again, past the direct, confrontational gaze of the four male figures within, and your eyes meet what should be a chaos of painterly reference, snaking lines and consumer product labelling: the laminate floor has the scratchy texture of an amateur woodcut, jarring against the neat arrangement of cabinets and furniture in primary colours.

Mondrian is very much in the picture here, as the title implies, in competition with a profusion of painted and collaged imagery that would have sent the Dutch artist into fits. Meanwhile, the tangled stems of a houseplant rhyme with an unruly black ceiling pipe, a line on a walk rudely interrupted by a dual-headed fitting. Few details in the composition feel obvious or, in some instances, anything more than incidental, but the parts add up to a barnstorming whole.

This approach is, at times, overwhelming. Marshall’s paintings of the mid 1990s introduce a number of motifs that push the compositions into almost whimsical territory: the Warhol-esque blooms and Disneyfied bluebirds swarming across the foreground of Watts, 1963 (1995), an idealised and unusually self-referential vision of the Los Angeles housing project where the artist lived in his youth; or, in Past Times (1997), the Snoop Dogg and Temptations lyrics spilling from a portable radio like the speech scrolls in Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque Triptych. Past Times – think Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe but transplanted to a Southside Chicago park – just about holds the attention through some less obviously attention-grabbing details: the exquisitely rendered pebble-dash coating a municipal bin, say, or an arc illustrating the swing of a golf club. Watts, 1963 communicates something altogether more mysterious, messy impasto caked over the prim lawn and neat facades of the housing. Here is a lament for utopian ideals of post-war living.

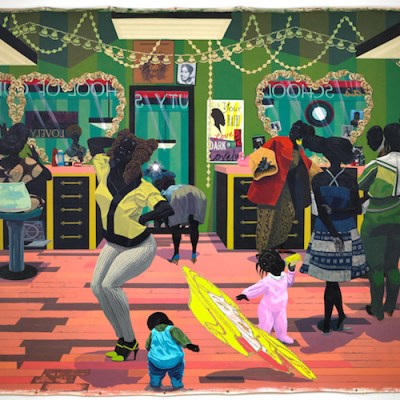

More recently, Marshall has reined things in, but outbreaks of the bonkers still keep surfacing. School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012) brings us back to the salon, but this time the patrons and clientele are women. If the way these figures are dressed doesn’t seem entirely naturalistic, small wonder: Marshall, according to an essay by Madeleine Grynsztejn in the superb exhibition catalogue, designed them himself, making actual garments with a Singer and modelling them on dolls he used as references for the composition. It reinforces the painting’s already palpable sense of realism bleeding into full-on irreality: it variously contains a series of glitter-edged, heart-shaped mirrors, a likeness of Disney’s Sleeping Beauty warped to the dimensions of the hovering skull in Holbein’s The Ambassadors and even a faithfully transposed poster for Chris Ofili’s 2010 retrospective at Tate Britain. Overhead lighting casts strobe-like rays as one woman breaks into a spontaneous dance.

Marshall can be solemn, portentous, improbable, joyous and slyly funny, sometimes within the space of a single canvas, mixing registers and messages to the extent that his paintings escape any simple, narrative reading. The Academy may have been an aspiration, but he is far too interesting an artist to be confined to it.

‘Kerry James Marshall: The Histories’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 18 January 2026.

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.