Success and fame, if they come to an artist at all, usually arrive by one of two routes. Either their work suddenly captures the moment, chiming with current cultural trends or concepts; or else an artist’s career is marked by more gradual progression, as their influence slowly grows and they themselves shape the discourse around them. In the case of Kerry James Marshall, though, it’s both of these at once. In just the past couple of years, his reputation has soared – both critically and commercially – to the extent that he is now widely regarded as one of the key artists of our time (Art Review magazine has ranked him number two on its latest annual ‘Power 100’ list of art-world influencers). And certainly his paintings, exploring themes of black identity and visibility, couldn’t seem more relevant or urgent – particularly in the context of his native US, where movements such as Black Lives Matter have forced such issues to the fore. Yet, if there’s been a shift in cultural awareness, then Marshall himself is also partly responsible. For more than 35 years his paintings have taken as their subject the representation of black figures – how they have been marginalised within the Western pictorial tradition, reduced to bit players within the mainstream narrative of art history. Indeed, ‘black lives matter’ could be regarded as the organising principle of Marshall’s project: an assertion that, contrary to what tends to be found on the walls of the world’s great museums, it isn’t only white people who are worthy subjects of art. His work is a way of subverting the racial bias – the white supremacy, you might even say – inherent to Western art.

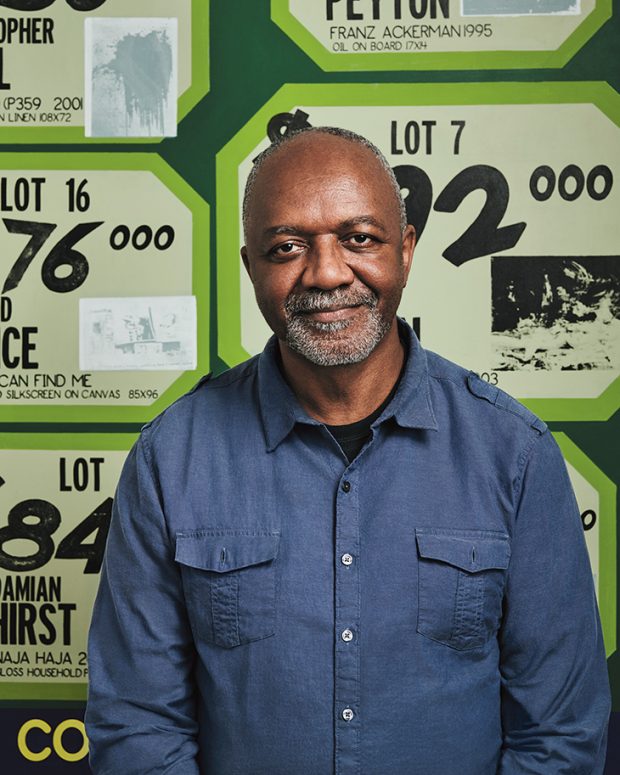

Aged 63, Marshall seems to relish his sense of mission, the self-imposed responsibility of creating what he has previously called a ‘counter-archive’ of paintings of black subjects. ‘Part of what I’m doing in my work is about attending to this absence of black representation in the historical narrative,’ he tells me. ‘But the question is always then, when you put black people in a picture, what should they be doing?’ It’s a bright October afternoon, the day before a show of his new paintings opens at the London branch of the international gallery empire owned by David Zwirner (incidentally ranked top in Art Review’s list), and Marshall and I are seated on the top floor of the Georgian townhouse that serves as the gallery’s premises. An expansive speaker, at once easy-going yet meticulous, he explains how there are certain tropes of blackness, various negative stereotypes that often dominate media narratives, which he refuses to pander to: ‘I don’t do pictures in which the figures are abject in any way. I don’t do pictures in which the figures are traumatised in any way. I’m trying to create a certain kind of normalcy; a kind of everyday-ness, a commonplace-ness – a sense of simple presence.’

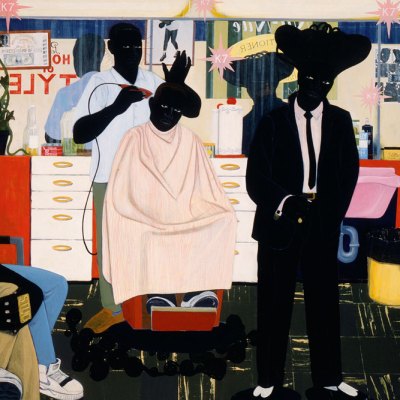

This sense of black people doing normal things, going about their daily lives, has become one of the hallmarks of Marshall’s work over the years. Often executed on a grand, mural-sized scale, his paintings depict intimate moments or elaborate scenes of activity, leisure, and communality. Barbershops, nightclubs, parks, domestic interiors, romantic meetings, family or community get-togethers: the sorts of tableaux Marshall offers up are those in which his subjects exist on their own terms. ‘I’m always concerned,’ he says, ‘that the figures in the work seem self-possessed, that they don’t exist there as a sign of anything.’ So they’re not there to fulfil a role, I ask, they don’t signify difference or otherness? ‘Right,’ he says. ‘Part of my project is to escape this kind of imperative that everything you do as a black person is always about lack. That there’s never a moment in which you have simple pleasure – where you’re just there, where you’re just simply being. And your being is not fraught with all these other layers of historical meaning.’

At the same time, his project is also about recognising the inherent contradictions of such an aim. After all, any attempt to subvert the category of blackness, to erase its sense of particularity or historical difference, is, simultaneously, to somehow reaffirm it, to pay it special attention – this in a way is the irresolvable paradox, the inescapable bind, of identity politics. Marshall acknowledges this in his work, even as he portrays his figures in everyday situations, by making their blackness more extreme, pushing the skin tones towards what in past writing and interviews he has called a ‘rhetorical blackness’. ‘That rhetorical black,’ he explains to me, ‘is the way we describe each other as people. Most people will automatically say, “Black people aren’t black, they’re brown”. But then, if you use that rhetorical figure of blackness, why not make it concrete, artistically? So that’s what I do. But I do it in such a way that it doesn’t become a reduction, it becomes rich and expansive. That’s really been of critical importance to me – the development of that black figure as a device.’

Marshall’s figures, then, aren’t any shade of brown, but are literally black – a deep obsidian, made even more darkly scintillating when set against the rich panoply of bright colours he typically employs for the rest of his scenes. In fact he uses several different types of black for skin tones, he tells me, starting with ivory black, carbon black, and iron oxide black, then mixing them with other hues. The point is, the various shades are all subtly different from each other, in the same way, for instance, that a selection of blues might be different. ‘If black is a colour, then you should be able to treat it chromatically the same way you’d be able to treat any other colour in a picture, chromatically,’ he says – so that his paintings, on one level, formally embody an ideal in which black is simply a colour designation, like any other, with no greater cultural significance.

‘If you looked at the palette I was using you’d think, “Well, that’s black, black and black next to each other.” And they don’t look so different. But when I use them in a painting next to each other, the differences become more apparent. Because the iron oxide black is inherently red. And if you stack that on top of carbon black, it obviously looks red. Or I’ll mix in cobalt blue, a chrome oxide green, an earth tone like raw umber or yellow umber. What I’m doing is changing the temperature, from cool to warm and warm to cool. And I use those to do what functions as modelling in the figures, even though I’m not doing modelling in the classical sense, I’m simply creating a set of patterns that help to give the figures some volume.’

It’s fascinating listening to Marshall talk not only about the ideology of painting and the politics of representation, but also about painting on a technical level. Or rather, it makes you realise how, for him, the two aspects are inseparable. His ambition has always been to achieve an expertise and proficiency to match the Old Masters whose paintings hang on museum walls, for his paintings to pass muster alongside the revered classics that make up the canon – because that, precisely, was the only way to contest the canon, to rewrite the master narrative of Western art history and pay attention to black subjects who were mostly marginalised or invisible. Not that his paintings necessarily look anything like works from the past: ‘I’m not interested in emulation, I’m not trying to paint in the same style,’ is how he explains his approach, ‘but to do the equivalent, nowadays; to apply the same kind of logic’. The idealised, classical poses of the grand manner, various bits of rococo ornamentation like something from Fragonard, the convention of using an artist’s studio as the setting for a painting – Marshall knowingly adopts such motifs like a sort of demonstration of credentials, a way of lending authority to his artistic argument. The main lens through which his work is often viewed, and how he himself describes it, is as an updated form of history painting – that most elevated of genres, according to 18th-century academic theory, in which moments of historical significance, as well as other types of narrative, are portrayed. Marshall’s project is a way of centralising black experience within history, a sort of claiming of history.

It’s possible to trace this historical preoccupation back to events Marshall has himself witnessed. Born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1955, during the beginnings of Civil Rights unrest, he was nine when his family moved to South Central Los Angeles – to Watts, initially, where the era-defining riots were shortly to erupt. Later, he lived close to the headquarters of the Black Panther Party. It was in Los Angeles that the desire to become an artist was kindled, on school trips to the County Museum to view works by painters such as Veronese, then through studies at the Otis Art Institute where he became influenced by the social-realist work of Charles White (1918–79). Marshall continues to champion White, he tells me, and recently wrote the catalogue foreword to a retrospective of his mentor’s work. Although at points in his career Marshall has branched out into other media – including sculpture, photography, and installation – a sense of social significance, of exploring how a historical moment disperses through everyday, lived experience, remains central.

Among his best-known pieces, for instance, is his suite of monumental Garden Project paintings from the mid 1990s, which riff ironically on the tradition of idyllic pastoral scenes, portraying figures picnicking on grass or laying flower beds within the grounds of various public housing projects – the sorts of developments that were the products of 1930s utopian thinking, but which by the time Marshall’s paintings were made, were more associated with poverty and high crime rates (boarded-up windows can be seen in the background). In other works, the historical implications may be less overt, the compositions less formal – yet there’s always a sense of narrative, of a representative moment being staged. School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012) depicts a scene in a busy beauty salon, the female figures posed and magnificently embellished with all the accoutrements of contemporary fashion, while a strange, stretched shape in the foreground functions as an anamorphic image – a device inspired by Holbein’s The Ambassadors – of a blonde, white woman, like some jarring invasion from another reality, a parallel standard of beauty.

Such works by Marshall, with their colossal size (sometimes more than 10 feet wide), teeming detail, and numerous art-historical references, are nowadays routinely, and rightly, referred to as masterpieces – a designation that would seem to indicate a kind of fulfilment of his project. Certainly, that was partly the implication behind titling Marshall’s widely acclaimed museum retrospective, which toured to widespread acclaim in 2016–17, ‘Mastry’ (the name was also derived from his epic superhero comic saga, Rythm Mastr [1999–ongoing], as well as punning on the history of American slavery). And his magisterial status carries over into the commercial world, too, if the auction sale last year of one of his Garden Project works, Past Times (1997), is anything to go by – its price of $21.1 million set a new record for a work by a living African-American artist (the buyer, it was later revealed, was hip-hop impresario Sean Combs).

The price tag, however, isn’t something Marshall feels particularly comfortable discussing, it seems to me. Or perhaps he’s disappointed the work was offered for sale at all. It had been owned by a municipal authority in Chicago, where Marshall has lived since the 1980s, and was on public display there. Certainly, a few weeks after our interview, a minor controversy erupted when the city of Chicago attempted to sell another publicly owned work of his, only to withdraw the sale when Marshall made his objections known. ‘Withdrawing the work was the right thing to do,’ states Marshall in a follow-up email. ‘Municipalities should not be exploiting their artist citizens for short-term gains.’

The challenge of producing new work after his retrospective is something he admits, during our interview, to finding daunting. ‘The problem with retrospectives is, how do you start up again? Because a retrospective seems like a kind of ending. But you know I’m not so old!’ he laughs. ‘I think I’ve got a lot more in me. So the question for me is: how do you begin again, so that it doesn’t seem redundant? So that it’s not like you’re simply going back to things you’ve done before?’

The show just about to open when we meet seems full of fresh directions. Titled ‘History of Painting’ – a play on Marshall’s reputation as a history painter – it seems to interrogate the various functions of painting, stripping away the sense of mystery and authority that the practice accrues for itself. Only one piece is on a large scale: Untitled (Underpainting) (2018) is a diptych depicting parallel views into a museum, where tour guides are giving talks to school groups – an alternative vision of how the coded language of art appreciation is taught, and to whom (all the figures in the crowded galleries are black). What makes the painting dramatically different from previous works is its technique: it’s essentially monochrome, done in shades of umber like an unfinished Renaissance piece that never had top colours added. For Marshall, it represents a personal link to the theme of pedagogy: ‘I’ve always been interested in unfinished underpaintings, like Leonardo’s St Jerome in the Wilderness – that’s how I learned how paintings were constructed, from those sorts of works.’

Other new paintings are even more of a departure, in that they move away from figuration completely. Though it would be a mistake to regard his arrangements of dancing, colourful lines and shapes as abstractions, he tells me – they’re more like a statement about what painting, at its most fundamental, consists of. ‘They’re fairly straightforward, and kind of rudimentary. It’s the rudimentary application of paint to a surface that arrives at a configuration that seems satisfying,’ he says, laughing again. Yet, as we discuss these works, his language can’t help but recall his strictures for how black people should be portrayed: ‘I was trying to make something where there’s no subtext, where the paintings simply are what they are. They have a kind of sufficiency, just being what they are.’

Most intriguing, though, in light of his stratospheric auction prices, and perhaps the only sort of response to them he truly feels like making, are a series of paintings where auction-lot sales figures – $420,000 for a Frank Stella, $628,000 for a Roy Lichtenstein – are presented like supermarket advertising flyers, bright and dazzling. Again, despite the fact the paintings contain just text and colours, they feel characteristic of his work as a whole, eye-catching and alluring, yet also measured, multilayered, offering the long view. ‘They’re not critiques of the art market,’ he insists, ‘they’re not just statements about the prices. They’re examinations of what the proper subjects for paintings can be. What happens to paintings can be as much the subject of paintings as anything else. One of their purposes, at this stage of history, has become simply to be exchanged in the marketplace. Somebody paid such and such amount for such and such a work on such and such a day – so in a way, that’s history painting too!’

From the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.