After about an hour of interviewing Kiki Smith in her as-yet-unfinished three-storey studio in a former train depot in a quiet rural town in upstate New York, I finally muster the courage to ask the question I have been dying to ask since we sat down to talk. ‘What are those blue dots on your arms?’

‘Oh,’ she says, seeming suddenly a bit shy, ‘these used to be stars, but now they’re dots.’ Evenly spaced along the backs of her arms and legs, the stars are, she explains, in imitation of the Egyptian goddess of the sky, Nut, whose body stretched across the earth and was covered in stars. According to legend, Nut eats the sun every night, and it exits her digestive system in the morning.

I can’t imagine a more perfect symbol for this artist, whose oeuvre is intimidatingly broad in scope and style. There seems to be no medium that Smith hasn’t tried and mastered: she is an expert draughtsperson, a renowned printmaker and a sculptor who has worked with every imaginable material, including beeswax, found objects, paper, glass, and bronze (for which she does her own casting, before a foundry makes the final work). She has also made videos and installation work. Moreover, her source material will make your brain hurt with its breadth and reach: she delves deep into folklore from all over the world, as well as fairy tales and religious icons. Most of the images she pulls from this archive are feminine. Smith has reclaimed ancient tales about womanhood and respun them to reveal that the virginal innocents were never as powerless as they seemed, and that the bitter, resentful crones who sought to murder their young and pretty rivals were themselves victims of the patriarchy. Thus she has portrayed Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother wearing red cloaks and emerging from a wolf carcass with complete calm in the mesmerising lithograph Born (2002), and has herself appeared in a series of photographs from 2000 as a sleeping witch. The work that I always think of when somebody mentions Kiki Smith is her set of sly Sirens and Harpies figures – mythical creatures that are part woman, part bird. These small bronze statues not much bigger than crows were displayed in Central Park, perched on boulders, during the 2002 Whitney Biennial.

Kiki Smith photographed in her studio in upstate New York in August 2019. Photo: © Nina Subin

Smith, who is astonishingly prolific and has maintained a steady, active and visible career since the 1980s, seems to be poised for renewed interest due to the swell of the #MeToo movement. Now, in 2019, with her work as resonant and relevant as ever, Smith is enjoying significant exposure in Europe, with a recent exhibition at the Belvedere in Vienna that originated at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, as well as separate shows at Modern Art Oxford (28 September–19 January 2020) and the Monnaie de Paris (18 October–9 February 2020). She recently donated all of her printed works to the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, which honoured the gift with an exhibition earlier this year. Over the summer, she had an exhibition at Dakis Joannou’s Deste Foundation project space in a former slaughterhouse on the island of Hydra, overlooking the Aegean Sea. For this space, she made two series of flags – gorgeous indigo-hued banners and milk-white pennants featuring drawings of constellations – that fluttered in the wind on a pathway leading to the building. In the building itself, she installed windows made of pink glass from Germany. In a review on Artforum.com, Lauren O’Neill-Butler described the effect of the pink glass against the setting sun: ‘I saw new colors.’

As we chat in a sitting area on the sunlit top floor of Smith’s new studio, we can hear the sounds of construction – drills, jackhammers, the beeping of trucks – while workers put the finishing touches on this space, building custom work tables on wheels that can be easily manoeuvred, and repointing the brickwork on the exterior. I had expected Smith to be formal, since her work is so grave, but she is thoughtful, wry, and warm, open about certain aspects of her personal life (on menopause: ‘It is like being kneecapped with a baseball bat’) and circumspect on others (on who her husband is: ‘He is a husband’), and especially evasive when asked to talk about her work.

Born (2002), Kiki Smith. Courtesy Scala/Art Resource, New York; © Kiki Smith

Smith resembles the folkloric figures she often depicts, with long wavy hair, now elegantly grey, and an ethereality that comes through in the musical lilt of her voice and her graceful, deliberate movements. One of the artworks hung on the walls near us is by a former student of hers; Smith is passionate about printmaking (which is why the show at the Pinakothek was of great importance to her), and has taught it at NYU Steinhardt and Columbia for years. ‘All my work comes from printmaking,’ she says. ‘This comes from my father’s work, turning models this way and that way, and seeing how pieces turn from one thing to another. A lot of my work is very repetitive like that: making a print, then a drawing, then a sculpture. You just keep turning it and turning it and it just keeps revealing some nuance. You can just have a spark or a thread of something and just keep watching it change, and bring up new meanings of things.’

Smith seems completely comfortable despite the flux of moving her studio from her home in the East Village. More than one writer has commented on the easy integration of Smith’s work and life; the way that her New York home and her persona seemed to complement her art – at one point, 30 live doves and finches flew freely around the place. She speaks fondly of growing up in an artistic family. Her mother, Jane Lawrence, a celebrated soprano, and her father, Tony Smith, a pioneer of minimalist sculpture, found ways to unite their careers with their family life. Lawrence was pregnant with Kiki while she was on tour in Europe, and timed a visit to Nuremberg to give birth in the US military hospital there. Smith was raised in suburban New Jersey, where she and her two sisters helped her father make paper maquettes for his muscular geometric bronzes while sitting at the kitchen table. ‘I know people who really struggled for the permission just to be artists,’ Smith says. ‘I think coming from a family of artists, you’re not in any kind of struggle with that. There may be other kinds of struggles, but there is no struggle with whether it’s something legitimate to do.’

Untitled (Five Seated Paper Girls) (2007), Kiki Smith. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Kiki Smith

Smith didn’t finish art school; she went to Hartford in Connecticut for a year and a half, and applied to the School of Visual Art in New York – but never checked to see if she got in, for fear that she had been rejected. By her own account, she was a poor student in high school, and at one point began training to be an industrial baker, before realising that wasn’t her calling. She also studied to be an EMT (emergency medical technician). When asked how she decided to become an artist, her answer is inspiringly simple: ‘I lived with someone who said if you want to be an artist, just be an artist. Being an artist is one of those things that is a self-proclaimed activity. There is no qualitative aspect to it at all, so you’re very free.’

The night before our appointment, I text a curator friend who has worked with Smith in the past, asking if she had any advice or suggestions for our interview. ‘If you can, let her draw while she is talking,’ she suggests. Armed with this knowledge, I ask Smith if she would like to draw while we speak, but she demurs. ‘That’s because I was premenopausal. When I was premenopausal, I was working all the time. Like every second of the day, I had to be doing something. After I’d been beaten through menopause, I’m more slow.’

Such earthy honesty is in keeping with an artist for whom bodily function and dysfunction have long been an interest, and who has made works such as the ground-breaking Tale, from 1992. It portrays a woman on all fours, cast in pallid beeswax, with a long trail of a black substance resembling shit streaming from her backside. The female body in Smith’s work is often subject to mutilation and dismemberment, as well as transformation (as in Sirens and Harpies). Animals began appearing with greater frequency in the early to mid 2000s, with works such as Born (2002) – a bronze sculpture in which a doe seems to give birth to a grown woman – melding female and animal figures. Smith has long used crows in her work, including a stunning floor-bound installation of more than a dozen dead crows from 1995 (a flock of crows is called, fittingly, a ‘murder’). It is a breathtaking work, in that it makes you feel like all the oxygen has been depleted from the room – a shrewd diagnosis of our era of dire ecological peril. In an indirect way, Smith often seems to be equating environmental injustice with violation of human rights, particularly those against women. There is an implicit finger pointing at an unfair hierarchy propped up by the patriarchal system, in which men are at the top, and women, children, and the natural environment inhabit the lowest rungs.

Born (2002), Kiki Smith. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Kiki Smith

Political concerns have never been far from Smith’s mind, but she is the last person to facilitate such – or any, for that matter – interpretation of her work. Not that she is deliberately obscuring her politics. Her breakout work was a multimedia piece that she created with her friend David Wojnarowicz for her first solo show, ‘Life Wants to Live’, at The Kitchen in 1982. Smith painted lurid tabloid headlines about women who killed their aggressors in acts of self-defence. The installation also included recordings and images from CAT scans, X-rays, and stethoscope exams made as she and Wojnarowicz beat each other. While the work was about domestic abuse and resilience in the face of violence, it seems strangely prescient (as is so often the case with Smith’s work), foretelling the Aids crisis and the complete absence of empathy and assistance from the US federal government. In 1988 Smith’s sister Beatrice died of an Aids-related disease, as did Wojnarowicz in 1992, so Smith was personally affected by the way Aids ravaged the New York art world. Her response was to push deeper into figuration. Nancy Spero was a key influence. Smith has said in the past, ‘When I first saw Nancy Spero’s work, I thought, “You are going to get killed making things like that; it’s too vulnerable. You’ll just be dismissed immediately.”’

Smith notes that figuration is common in contemporary art these days, but when she was starting out in the 1980s, it was not so widely accepted. At that time, Smith participated in the art collective Colab (short for Collaborative Projects Inc.), which gave priority to the success of the group over the individual, and staged interdisciplinary exhibitions such as the ‘Times Square Show’ in an erotic massage parlour. During the ’80s and early ’90s, performance art, identity politics, and conceptually inflected art were far more prevalent than figurative painting or sculpture, which means that Smith has long been a bit of an outlier. The relatively recent embrace of figuration isn’t the only societal shift that has affected the reception of her work. After she was first invited to participate in the Venice Biennale’s Aperto section, a showcase for younger artists, the invitation was withdrawn upon further consideration that Smith was in fact too ‘old’ for the exhibition. Smith laughs off this humiliating and stupid decision with admirable nonchalance. In any event, she was invited by Jeffrey Deitch to participate during the next Aperto, in 1993, which turned out to be a landmark show (she was also included in the Biennale in 2017). ‘I didn’t get to show until 10 years after my male peers. If you can outlive most men, all of a sudden you can be venerated.’

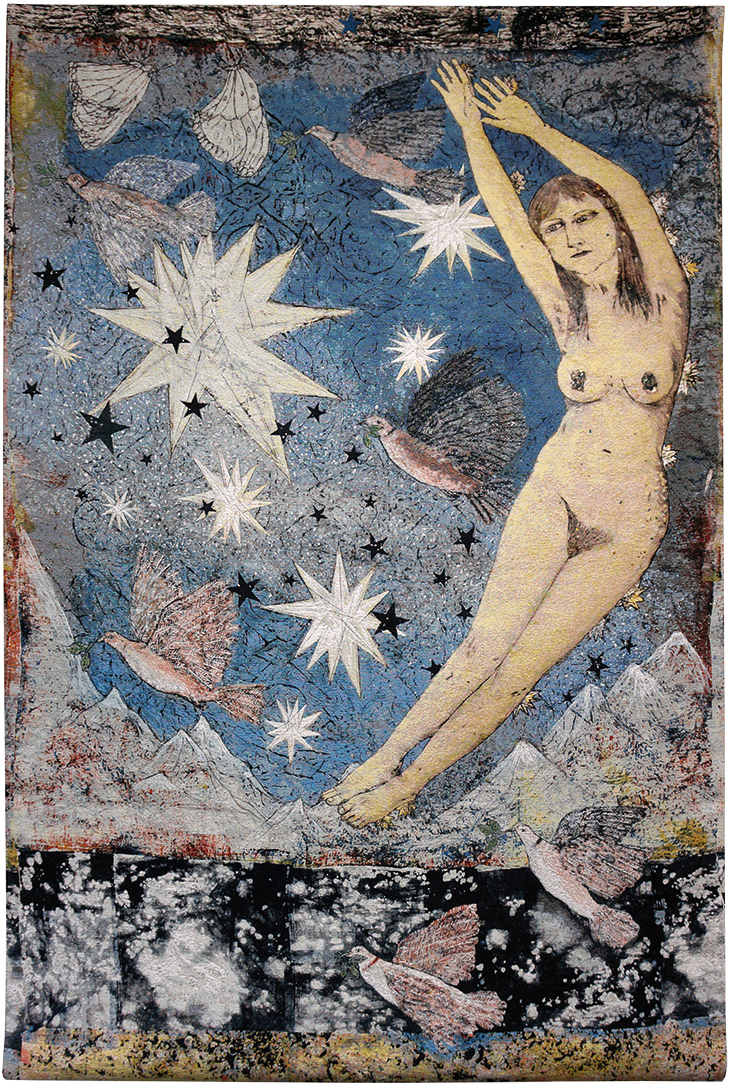

Sky (2012), Kiki Smith. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Kiki Smith

The next incarnation of Smith seems looser, and even more mystical, if such a thing were possible, because of her openness to incorporating colour in her work, a shift that happened for her when she started making tapestries, around 2011. Smith creates designs from collaged paper at scale – usually ten feet high – and then sends them to Magnolia Editions in Oakland, California, which works with a weaving studio in Belgium where they are fabricated on a computerised loom. The earliest tapestries feature a nude woman enmeshed in a natural landscape. In Sky (2012), a woman floats over craggy mountains, keeping company with birds and stars in the vivid blue-grey heavens. A tapestry titled Congregation (2014) is composed of a nude woman seated on the branch of a tree, a network of lines connecting her eyes to those of a nearby deer, bat, and squirrel. The background resembles an ikat textile, with intersecting white and blue shapes, and there are subtle hints of rich colour, such as scarlet and emerald green, on the lower half of the work. ‘I used to say that I want my work “like a New England tombstone”,’ she says as she describes her decision to include colour in her work. ‘Colour seems too personal, self-expressive to me – too scary.’

Since Smith is hardly someone who has shied away, at any point, from trying something new, it is hard to take this at face value. She channels Nut, after all, the goddess who devours the sun for her nightly supper. I use the final minutes of our interview to ask this artist, who has lived through some serious political upheaval in her lifetime, what she thinks of our current moment of global turmoil. She pauses before saying that the thing that seems the worst now is ‘this seething hatred everywhere’. But there is some cause for optimism. ‘It always seems like there are ways the culture is expanding and ways it is contracting. Sometimes I think in the contraction, where it’s trying desperately to contract, it’s because those paradigms are over with already, the shift has already happened. The fightback against progress is, to me, an indication that the battle has already been lost.’

‘Kiki Smith: I am a Wanderer’ is at Modern Art Oxford until 19 January 2020; ‘Kiki Smith’ is at the Monnaie de Paris until 9 February 2020.

From the October 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.