From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Just across the Thames from the Houses of Parliament and over the road from St Thomas’ Hospital there is a 320m-long wall, behind which hides one of the largest private gardens in London. The largest, at Buckingham Palace, belongs to the Queen; this one, attached to Lambeth Palace, belongs to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Big as it is, the garden is nevertheless half the size it once was; Archbishop Campbell Tait opened some nine acres of it for the benefit of the poor in 1869 and that site was formalised as the Archbishop’s Park in 1901. The other half, which dates back to 1197, remains the retreat of the archbishop. It is where the current incumbent, Justin Welby, takes his morning run and where a previous office holder, Rowan Williams, had a wigwam for private contemplation.

The garden now has a new addition. At the northern end, where Lambeth Palace Road kinks towards Waterloo Station, a nine-storey brick bastion – a modern-day nod to Morton’s Gatehouse, the Tudor entrance to the palace built in 1495 – now rises from the curtain wall. The building is the new Lambeth Palace Library, a mixture of storage, reading rooms, offices, seminar spaces, a lecture room and a conservation studio, that replaces the somewhat ramshackle provisions that had previously been in place.

A studio in the new building’s conservation wing. Photo: Hufton & Crow

One of the oldest public libraries in England, Lambeth Palace Library was founded after a provision made in the will of Archbishop Richard Bancroft upon his death in 1610. Its collection centres on the records of the archbishops of Canterbury as well as the Church of England archive, and represents the most important collection of religious books and manuscripts in Europe outside the Vatican. The items had previously been stored in 20 different sites within Lambeth Palace – taking over part of the Tudor entrance and the Great Hall – as well as incorporating the Church of England record centre at Bermondsey (in a former beer-bottling warehouse) and the Church Care library in Westminster.

Declan Kelly, Director of Libraries and Archives at the palace, describes the collection as ‘a bit of a cuckoo’ in the way that over the centuries the books moved in, colonised the rooms and ejected the original inhabitants along the way. The result was not just that spaces such as the Great Hall had ‘books, manuscripts and archives spread everywhere’ but that these purloined rooms were not up to the job. ‘Whenever it rained hard, I used to get worried,’ Kelly says. There was mould in some of the rooms, and comparisons with identical books held in Oxbridge colleges have shown that some 80 per cent of Lambeth’s collection has suffered pollution damage.

When the original collection was first housed in Lambeth Palace it was one third of a clerical three-part arrangement: eat, work, pray. There was the Great Hall for the first, the library for the second and the chapel for the third; together they formed a self-contained community around the archbishop (there is even a prison where John Wycliffe’s followers, the Lollards, were caged for heresy). The new library, the first new building at the palace site for 185 years, is dedicated simply to work, and the older buildings, freed of their books – and the temperature controls, structural strengthening and other restrictions that came with them – can regain their original purposes. The new tower meanwhile is an iteration of the various towers that successive archbishops built to leave their mark on the palace (its brick construction also suggests a fellowship with Tate Modern, further along the South Bank).

A new pond makes reference to medieval monastic fishponds. Photo: Hufton & Crow

The library (the cost of which, £23.5 million, has been met in full by the Church Commissioners) is the work of Wright & Wright Architects, who won the commission over the likes of bigger-name practices such as Zaha Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron partly for the way they pushed the building to the very edge of the site. The footprint is modest, occupying just three per cent of the garden, with the main building following – indeed incorporating – the boundary wall, and the conservation wing jutting into the garden as the bottom stroke of the letter L. It has windows looking north but a blank wall on the palace side, so the archbishop’s jogging privacy is not compromised. In the crook of the L is a new pond, a decorative reference to the fishponds of medieval monastic institutions, which turns the area into wetland nature reserve (already discovered by herons); Dan Pearson Studio has been tasked with the landscaping and planting around the building.

The other thing that recommended Wright & Wright was their expertise as library specialists. They have plenty of experience with historic settings such as the libraries at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge and St John’s and Magdalen in Oxford. And there is something of an Oxbridge college feel to the Lambeth Palace project. For Clare Wright, the leading architect, sensitivity to the site was a key part of the brief. The building sits on a once-in-100-years flood area, so in the event that the Thames Barrier fails, the books must be protected. Rather than being kept in a subterranean warren, they are stored between the second and sixth storeys in what are essentially sealed concrete boxes. This not only gives them four hours of fire protection but a stable environment in which the temperature and humidity are passively controlled by the concrete itself, with mechanical interventions taking place only when necessary – in winter, for example. In case of fire, the storage rooms and their 20,000 linear metres of shelving have a mist sprinkler system which sprays rather than douses the affected area, minimising damage. Elsewhere, rainwater is channelled into the pond; 50 per cent of the building’s electricity is generated by photovoltaic panels on the roof; and the building also shields the garden behind from the noise and pollution generated by the traffic on Lambeth Palace Road.

Externally there are few clues as to its purpose. Wright & Wright treated the library as ‘an inhabited wall’ and used three different types of brick (some 300,000 of them in total) to give the structure ‘a tweedy look’; there is a series of small brick crosses that climb up part of the facade – waggishly christened ‘bishop’s bond’ – and some banding; on the rear elevation recessed brickwork gives a grid pattern; and windows have a shadowed surround to give variety to what is a largely unadorned building, but that’s it. The street-facing windows are small, the entrance unshowy and the signage discreet.

At the top of the tower, however, the architects have built a light-filled lecture theatre, two sides of which have a deep viewing platform with Lambeth Palace itself the axis of one aspect, the Houses of Parliament the axis of the other. At night, when illuminated, the top storey acts as a lantern or the flame of a candle.

Internally, the founders’ intention that the library should be a resource for all has been strengthened: the public as well as readers can step in off the busy Lambeth Palace Road and find themselves in a lofty but not overbearing atrium with water and greenery in front of them. The transition from urban and noisy to rural and contemplative is both instant and striking. The new library also has an exhibition space for the first time so that some of the plums of the collection can be shown and their stories told. Historians interested in clerical history can head for the reading room, passers-by looking for a moment of calm and diversion can head for the vitrines and display spaces.

While construction began in the spring of 2018, the collection was only transferred to its new site in May this year. It was a lengthy task; the original 1610 collection numbered some 6,000 volumes and was thought by James I to represent ‘a monument of fame’ in his kingdom, while Peter the Great, on a visit in 1698, was astonished that there were so many books in the world. There are now 120,000 books, 4,600 manuscripts, 40,000 pamphlets, as well as maps, plans, deeds and photographs in the library’s keeping, with provision for up to 20 per cent more until digitisation catches up with modern archbishops’ record keeping.

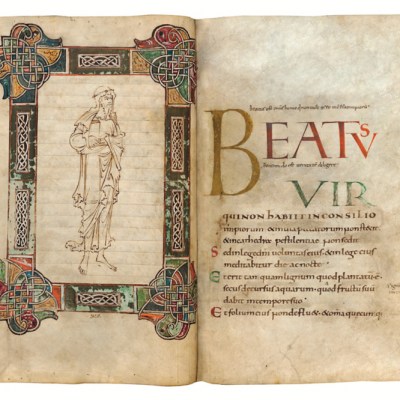

The earliest volume in the collection is the MacDurnan Gospels, a small illuminated volume probably made in Armagh in the 9th century. It includes assorted Celtic knot and diamond decorations and full-page illustrations of the four evangelists, as well as four miniatures of New Testament episodes taken from a 13th-century English psalter that were incorporated at a later date. Although it is not entirely clear how or when the volume entered the Lambeth Library collection, is has been in England since the early 10th century, when it was gifted to King Athelstan.

Portrait of Saint Matthew in the MacDurnan Gospels (ninth century), Armagh(?). Lambeth Palace Library, London

The volume is one of several with royal connections. Others include a book of hours that once belonged to Richard III and which was in his tent at the Battle of Bosworth, where he died. It includes a handwritten Latin note – thought to have been inserted by the king himself – on the calendar page for October, which translates as: ‘On this day was born Richard III, King of England at Foderingay [Fotheringhay] in the year of Our Lord 1452.’ Then there is a copy of Invicta Veritas, a book pronouncing on the indissolubility of marriage, written by Thomas Abel, Catherine of Aragon’s chaplain. Henry VIII bought up every copy of the book he could find to halt its dissemination, but this one he preserved, and wrote counter-arguments to Abel’s points in its margins. Deeper engagement did not lead him to respect the cleric: Abel was executed in 1540, two days after the architect of the royal divorce, Thomas Cromwell, had met the same fate. Elizabeth I’s prayer book is here too, as well as a copy of the execution warrant for Mary Queen of Scots – signed by Elizabeth after the original document went missing – that was saved for the nation in 2007.

Other books chart the path of Christianity as the language changed. There is, for example, the Lambeth Homilies, a collection of 17 sermons written c. 1200 in Old English when Middle English was the more common form. A manuscript of the 1350s, meanwhile, written in Anglo-Norman French, contains the words to a jeu parti – a debate on the themes of love, sex, wealth, and how a proper troubadour should behave – that was sung rather than spoken. An alternative to clerical Latin is evident in a rare copy of the Gutenberg Bible, written in English and dating from the 1450s. And while Minuscule 473, a Greek manuscript in which all four Gospels are transcribed on 309 parchment sheets just 28cm tall, came from Constantinople, St Alban’s Chronicle, written in the 15th century, probably had its illuminations produced in Bruges and details medieval English myth and history.

Detail from a page of the St Alban’s Chronicle, showing the killing of Edmund Ironside (late

15th century), England and Bruges. Lambeth Palace Library, London

For visual rather than verbal potency, the library holds both The Lambeth Bible, one of the most striking surviving Romanesque Bibles, made in England c. 1150–70, possibly for King John, and The Lambeth Apocalypse, an illuminated manuscript of St John’s Apocalypse dating from c. 1260 and including 78 half-page images. While the former is startling for its magnificence, the latter is notable for the imagination and vividness in which the Apocalypse is imagined – it is a church-wall Doom painting compressed in size but expanded in horror.

Page from the Lambeth Apocalypse, depicting scenes from the life of Theophilus of Adana (late 13th century), London (?). Lambeth Palace Library, London

Alongside such rarities is a vast amount of more workaday material relating to the Victorian church-building boom, including architects’ plans and stained-glass designs, and photographic records of the restoration and regeneration of church buildings that followed the destruction of the Second World War. We also find the correspondence of influential clerics, such as Hugh ‘Dick’ Sheppard (1880–1937), who as a Cambridge undergraduate was a member of the Bad Eating Club and famous for ingesting jelly through his nose, but who as vicar of St-Martin-in-the Fields was a tireless supporter of the area’s down and outs. As Declan Kelly says, although the library is digitising material as fast as it is able, there are rich pickings still to be found for any number of assiduous doctoral students.

The new library will also be home to a collection of prodigal-son books. In the mid 1970s the then librarian noticed a sizeable gap on the shelves, and on checking the card index to find out exactly what was missing, discovered that the relevant cards had disappeared too. Although both the police and antiquarian and rare-book dealers were notified, there was no sign of any of the books until 2011. Then, the new librarian, Giles Mandelbrote – still in charge today – was contacted by a solicitor with the story of a recently deceased client who had written a death-bed confession admitting that he had stolen the books and revealing their hiding place in a London attic.

The bibliomaniac was a former employee at the library who had used the fact that some 10,000 books had been destroyed by an incendiary bomb during the Second World War as cover: the volumes he took were assumed to have gone up in smoke. Mandelbrote had expected to find some 60 pilfered volumes; instead the cache contained 1,000 books, many of which had come from the library’s founding collection. Among them were an early edition of Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part Two, and Theodor de Bry’s hugely important illustrated chronicle of early European expeditions to the New World, America. Security at the new library will be rather tighter than in the 1970s.

Gloves given by Charles I on the scaffold to Archbishop Juxon (17th century). Lambeth Palace Library, London

Not everything in the Lambeth Palace collection is on paper, however. Among its selection of curious objects are the gloves worn by Charles I on the scaffold at Whitehall and a silver dagger that may have been made for the pope-burning procession in London of 1679 – a reaction to Titus Oates’s revelation of a fictitious Popish plot to assassinate Charles II. There are also two volumes of watercolours by John Bird Sumner (archbishop from 1848–62), the first of which was presented to the Library in 1917 by A.C. Benson, himself the son of an archbishop of Canterbury but best known for his lyrics to ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. The pictures are quietly accomplished but poignant souvenirs of how the nation’s leading cleric found his relaxation.

Perhaps the oddest item, though, is a tortoiseshell – all that remains of a creature that once belonged to William Laud, who as archbishop was a stout defender of Charles I’s royal prerogative and espoused a strictly uniform and hierarchical Church of England. Laud was arrested during the Civil War and beheaded in 1645, but his tortoise survived him, apparently making it to 120 years old before, in 1753, it too was executed – albeit accidentally, when a gardener dug it out of its winter hibernation and it died of frost shock.

The library holds Laud’s papers, including those found in his study when he was arrested, so it would be fitting to reunite the tortoise with the records of the man who once owned it. The animal may not have been as holy as many of the other rare items in the Lambeth Palace collections, but it was once an object of veneration and study too.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.