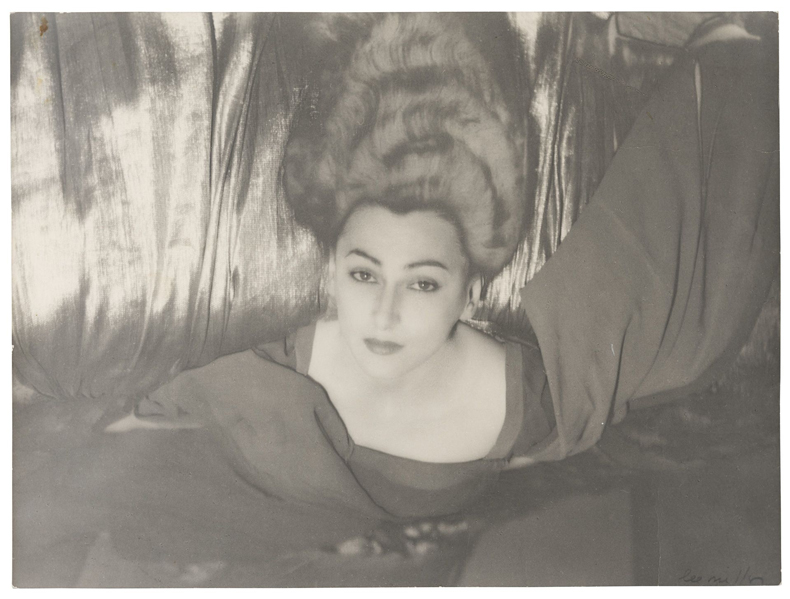

Among the Surrealist nudes and portraits that Lee Miller made in her twenties nearly a century ago, working alongside Man Ray in Paris, one photograph hanging in the ongoing retrospective at Tate Britain (until 15 February 2026) was discovered only recently. It is a photograph of Nimet Eloui Bey (c. 1930–32), a woman of Turkish Circassian descent who was exoticised in her day as ‘the first Oriental model’. Like Miller, she modelled for Man Ray and posed for Vogue magazine; a few years after the photograph was taken, her husband, Aziz Eloui Bey, left her to marry Miller. The real story here, however, is not the artwork’s links to Miller’s love life, but the fact that this vintage print was not previously known to exist.

Outside of Farleys House and Gallery, the Sussex home where Miller spent her later life with her second husband, Roland Penrose, exhibition-quality vintage prints are extremely scarce. She had just one solo show in her lifetime, which was not a commercial success, and the prints that she made for her New York dealer, Julien Levy, went mostly unsold. After she died, her son Antony and his wife Suzanna were rooting through the attic at Farleys when they stumbled across boxes filled with Miller’s negatives and prints; were it not for their discovery, her work might have forever slipped into the obscurity that she seemed to embrace after returning from capturing the horrors of wartime Europe.

This latest discovery in Paris is a striking portrait of Bey in repose, her head hanging from a bed but presented upside down so that her shock of hair appears to flow upwards. Employing a darkroom technique that Miller and Ray had recently pioneered, the image was solarised to give her locks a silvery glow. Hilary Floe, senior curator of modern and contemporary British art at the Tate, had first spotted the uncredited image in an obscure Surrealist publication, Le Phare de Neuilly, and felt sure it was by Miller – but without a print she couldn’t prove it.

Then, in November 2024, Fanny Schulmann and Adelaïde Lacotte from the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, to which the Miller retrospective travels next spring, were searching through Jean Cocteau’s archives at the Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris for material related to his experimental film, The Blood of a Poet (1932), in which Miller plays the role of a statue that comes to life. There, among his papers, is the photograph with Miller’s stamp on the reverse. ‘It was a real gift for the show,’ says Saskia Flower, an assistant curator at Tate who also worked on the retrospective, ‘especially as even Antony Penrose said he’d never seen it before.’

‘Vintage’ is the term usually given to prints that were made at or close to the time the negative was made, often becoming the master that the photographer would later match against. In Miller’s case, that means prints she produced herself in Paris and New York in the early 1930s, or those made under her supervision at British Vogue during the Second World War. ‘It’s about authenticity,’ says Zelda Cheatle, a curator and one-time gallery owner who was the first to show and sell Miller’s work after the attic discovery and help rebuild her reputation. ‘If the print was made when the negative was made, that’s how she wanted it represented. Someone else printing later is always making an interpretation […] A vintage print has presence, an emotional depth. Even people who think they can’t tell the difference can feel it. With a modern digital print, you might as well be looking at a book.’

Prioritising prints made by her own hand was a way of keeping Miller the artist at the centre of the show – which meant some detective work, resulting in the find in the Cocteau archive. But, remarkably, the Tate team also discovered vintage Miller prints much closer to home, uncovering two portraits of Eileen Agar, donated by the artist among a tranche of her own work. The exhibition also borrows from the Art Institute of Chicago and the Philadelphia Art Museum, who acquired vintage Miller prints through the holdings of Julien Levy, as well as from private lenders and the archives of Condé Nast, who gave the curators unprecedented access.

Vintage Miller prints might have been rarer still, says Ami Bouhassane, Miller’s granddaughter and co-director of Farleys House and Gallery. The materials pushed into the attic had been sitting for nearly 30 years under an open water tank. ‘I’m just glad it never leaked. They’d been crammed so tightly together that they sort of self-insulated […] It could have been much worse, she could have burned them. This is a farm, we always had bonfires, and it would have been easier than taking them up to the third floor. But on some level she wanted to keep them.’

The archive rarely sells any of its vintage prints. Only duplicates are ever deaccessioned, and then solely to fund conservation: the first, Exploding Hand (1930), was sold to the Victoria and Albert Museum in the 1980s so the family could afford acid-free envelopes for the negatives. In 2003, three wartime prints were sold to the Getty to finance a climate-controlled store. ‘Every sale has been about preservation,’ says Bouhassane.

The scarcity of vintage prints also reflects how photography itself was regarded in Miller’s lifetime. ‘There simply weren’t that many made,’ Cheatle says. ‘She cared about the printed page, not the print. She wasn’t Edward Weston crafting exquisite objects; she was producing images for Vogue.’ More crucially, she was not taken seriously as an artist. ‘She was a woman. She was considered a muse, Man Ray’s assistant, and wasn’t given credibility as a photographer. It’s taken decades for that to change.’ This is what lends the vintage prints their quiet force in the exhibition: at long last they return Miller’s artistry to view.

‘Lee Miller’ is at Tate Britain, London, until 15 February 2026.