From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Lee Ufan is a citizen of nowhere, a habitué of in-between spaces. Born in what is now South Korea in 1936, he moved to Japan when he was 20 and studied European philosophy. (Decades later, he’d resettle in Paris.) The paintings and sculptures he began making after pivoting to art in the mid 1960s, as seen in the opening room of this 1968–2023 retrospective, which brings together around 50 works, might suggest a different kind of interzone: to Western eyes, at least, they seem like Asian takes on American stylistics. Landscape I and II (both 1968/2015), widescreen colour-field canvases in fluorescent orange and pink, recall late 1960s post-painterly abstraction and West Coast finish-fetish fizz. But Lee’s understanding of modernity was modulated by the fact that when Japan ruled over Korea from 1910–45, his country was subjected to a fierce modernisation plan. For Lee, this fused modernity irrevocably with colonialism, indicting modernist art in turn. He wanted an approach to art that didn’t privilege the domineering auteur, imposing their subjectivity. Yes, Lee was the maker of these paintings, but their spaciousness was in the interests of partial self-erasure.

For much of Lee’s practice since then, this has meant paring back noisy excesses of self-expression. He creates situations that encourage the viewer’s active negotiation, particularly through attentiveness to materiality and implicit order. (If you don’t sign up for that and take the work with luxuriant slowness, Lee’s art can underwhelm.) Here, the stakes quickly become apparent in a selection of his Relatum sculptures, also begun in 1968, by which time Lee had become part of the Tokyo-based group christened Mono-ha or ‘School of Things’ for their interest in mixing industrial and natural materials and techniques. Relatum – The Avalanche (1970/2023) is a propped stack of rectangles in cool grey steel, each the dimensions of a mid-sized canvas, arranged as if sliding down a wall and spreading across the floor at precise angles, title and form suspending the work between culture and nature. Grasping the metaphor and the work’s visual dynamism quickly, the viewer is left with a leisurely, weirdly gratifying perusal of each sheet’s individuated patina, its thing-in-the-world specificity.

Relatum – Silence Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin. Photo: Jacopo La Forgia; courtesy Studio Lee Ufan; © the artist/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Relatum – Silence (1975/2023) introduces a conversation that will repeat: the nature/culture meeting of steel and stone. Here, a pair of curved steel sheets are pinioned against the wall by a mottled grey rock; another sits beside it as a backup. Amid the arrangement’s playful drama, the work’s paired textures serve as a constant eye refresh. In this sense, Lee’s work does share the same impulse that drove the American minimalists: to make the viewer home in on materiality in an almost psychedelically intense way. It’s just that in Lee’s universe, each thing must find its opposite, the work suspended between forces.

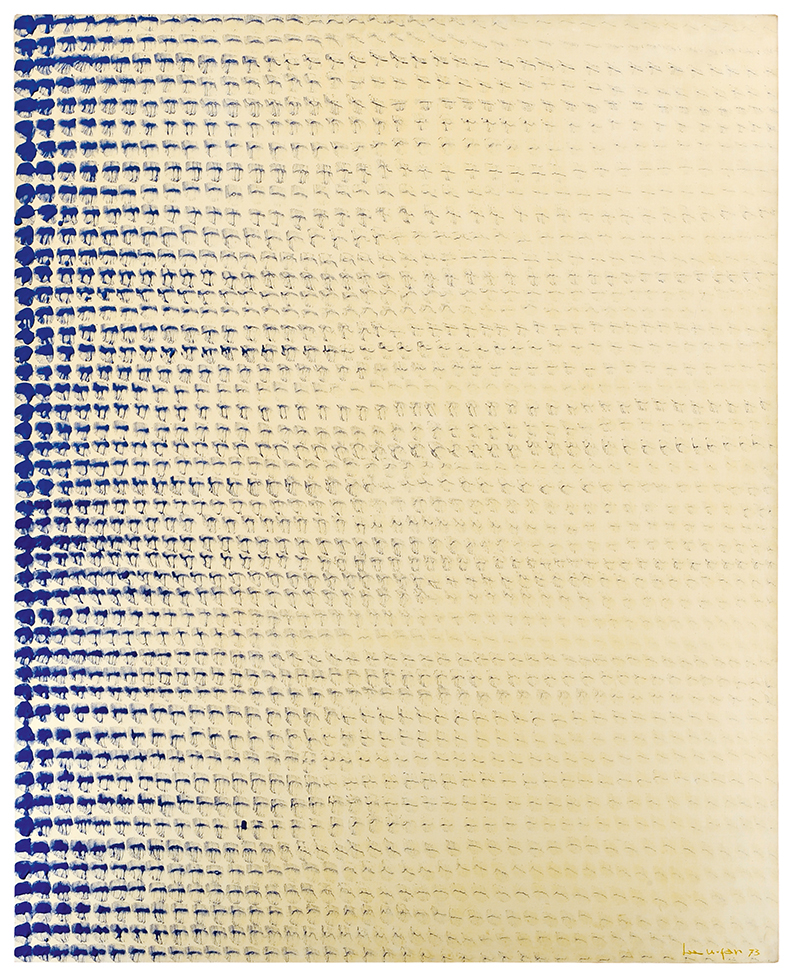

That’s even more apparent in his twinned painting series From Point and From Line, dating from 1975–82. In each of the From Point paintings, Lee appears to have dipped the end of a small squarish brush in either blue or orange paint – complementaries, though never sharing a canvas – and then repeated a single brushmark horizontally across a warm ground until the paint runs out. Sometimes one line of marks strides increasingly quietly across a single panel; sometimes there are battalions of them, the result intensely rhythmic. As you move in, granularity asserts its virtues. It’s evident that Lee is using a mineral pigment that sparkles pleasingly as it catches the light, and that he’s mixed it with adhesive. As the brush marks thin out into nothingness, a square of clear shininess progressively takes over until it’s all that remains. (If you want to read these works as pertaining equally to the pragmatics of painting and to mortality, go ahead.) In the From Line paintings, meanwhile, Lee arranges rows of dragged brushstrokes that peter out into nothingness; they look, surprisingly thrillingly, like tiers of rockets all going off at once.

From Point (1973), Lee Ufan. Courtesy Gallery Yonetsu, Tokyo; © the artist

After this, Lee appears to have wanted to bring nature and culture together not only within sculpture but also within painting: the With Winds canvases from 1988–91 equate flurries of grey brushstrokes with eddying gusts. As the series goes on, though, he seems to have hit on the idea that a painted mark might be both breezy and sculptural. To these eyes at least, it doesn’t work. The paintings, while retaining a clear intention of balance between brushstroke and pale background, turn leaden, inert. When Lee reboots his practice in the early 2000s with the Dialogue paintings, the results offer more to admire: here, he populates acres of white space with gradated columnar forms that suggest a brush carefully loaded with one colour plus white dragged across the canvas, moving from grey, blue or red to white. All Lee’s interests in form and emptiness, and his immense sense of balance, are on display. Even so, again, the canvases come off as thesis statements.

Relatum – The Narrow Sky Road (2020/2023), Lee Ufan. Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin. Photo: Jacopo La Forgia; courtesy Studio Lee Ufan; © the artist/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

If such works suggest an artist who once suspended himself between painting and sculpture but increasingly teetered towards the latter, it’s notable that, in this display at least, Lee’s three-dimensional work never falters. A highlight of the exhibition is a new Relatum installation given its own walk-in room, the floor carpeted with chipped white stones. Crunching towards the centre, you reach a long length of mirrored glass, like a rectangular pool in a Japanese garden, across which two big rocks mutely observe each other. At the mirror’s far end, and invertedly reflected, is Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Velvet Beret (1634, borrowed from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin where, Lee being his harmonising self, a second rock installation sits in front of another Rembrandt). Count the ways in which everything in this work is equalised by everything it’s not: sculpture and painting, abstract and figurative, Western and Eastern, past and present, cultural and natural, directing you to the floor then bouncing you on to the ceiling, as human as our greatest portraitist and as cold as stone. A system of mutual heightening, it brims with abstract feeling but finally says only what a viewer brings to it. It’s Lee Ufan and Rembrandt, and Lee Ufan and you, all somehow equal partners.

‘Lee Ufan’ is at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, until 28 April.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.