Léonce Rosenberg was one of the most influential and divisive dealers of the interwar period. Many could not forgive his willingness to profit from the auctions of stock seized from the German-born dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler after the outbreak of war in 1914. Kahnweiler’s forced exile in Switzerland allowed Rosenberg to put many of his rival’s stable of painters under contract and present himself at the forefront of cubism; he opened a gallery, L’Effort Moderne, in January 1918. Cultivating a dynamic, aggressive, even aristocratic mode of masculinity, reinforced by his admiration for England and English business, Léonce’s passionate belief that the art dealer should also be a patron, actively involved in the artistic process, was poles apart from his more discreet and commercially savvy brother, Paul. An idiosyncratic thinker, Léonce Rosenberg also sought to propagandise on behalf of cubism, which he understood in reference to long trends within French art and the development of civilisations. In the memoirs of the painter Gino Severini, Rosenberg sometimes ‘acted like a missionary preaching his own esoteric religion’.

A fascinating demonstration of Rosenberg’s cult of modern art can currently be seen at the Musée Picasso in Paris, in an exhibition that reconstructs the contents of the dealer’s apartment at 75 rue de Longchamp in the 16th arrondissement. Rosenberg’s house was a total work of art, a vast decorative scheme that was also a key document in the history of interwar modernism. The decorative scheme began in earnest in 1928, but Rosenberg’s interest in how art could inhabit domestic space had a longer gestation. The first to exhibit Mondrian in Paris, in 1921, Rosenberg had been fascinated by the De Stijl movement, with Theo van Doesburg coming up with designs for a proposed hôtel particulier. If this functionalist villa was never built, the way in which Rosenberg combined modern art with classic French style was no less remarkable. For, in contrast to dealers who chose to live among their past acquisitions, Rosenberg commissioned entirely new works for the space. All of these were delivered and installed in only 15 months. While the resulting ensemble was a useful opportunity for artists to promote themselves, for the dealer, it was a way of demonstrating his authority as a new breed of ‘amateur’. In an intriguing twist, Rosenberg paired his modern pictures with his collection of furniture from the Empire, Restoration and Louis Philippe eras and objets d’art; a photograph of his daughter Madeleine’s bedroom reveals that Max Ernst’s Fleurs de neige (1929) was hung immediately above a 19th-century porcelain basket of fruit and flowers. While the furniture is largely missing from the exhibition, the overall design conveys the distinct character of each of the 11 rooms and the lengths to which Rosenberg went to create resonances and harmonies across potentially clashing pieces.

Léonce Rosenberg in the storeroom of L’Effort Moderne, c. 1913–21. © Fonds Rosenberg RMN/© ADAGP, Paris, 2023

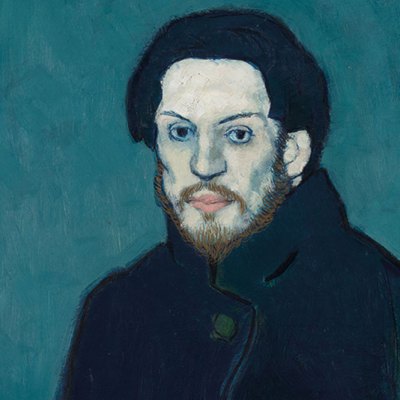

The Musée Picasso is in many ways an ideal setting for this show, even if Picasso’s own relations with Rosenberg were stormy. There is no hint of these tensions in the elegant, linear portrait drawn by the artist in 1915, in which Rosenberg posed in front of the very first Picasso canvas he purchased, Harlequin (1915; now in MoMA). Within a couple of years, Rosenberg’s clumsy attempt to assert control over his artists’ collaborations, and unwillingness to meet Picasso’s soaring prices, led them to fall out. In the catalogue, curator Juliette Pozzo argues that the grotesque pair of Managers that Picasso created for the ballet Parade in 1917 was modelled partly on Rosenberg, of whom he famously exclaimed ‘Le marchand – voilà l’ennemi!’

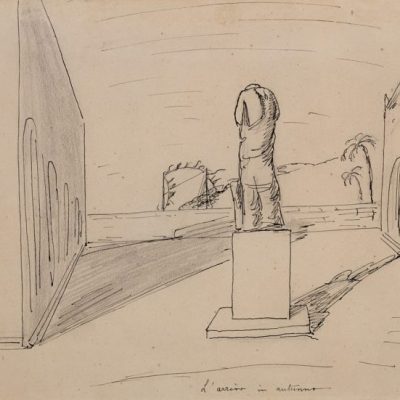

To adorn his apartment, Rosenberg instead called upon Picasso’s peers, both famous and now forgotten, each working in their own idiom. The so-called hall des gladiateurs was dominated by Giorgio de Chirico, from whom Rosenberg requested 11 paintings on antique themes. After his return to Paris in 1925, de Chirico was the height of fashion and the dealer evidently loved how these archaic scenes complemented the neoclassical furniture; he even compared their effect to Gobelins tapestries. Combat is a riot of oily, muscled bodies, human and equine, with enervated poses and grotesque expressions, both stagey and deflated. Another declension of the classical tradition was found in Madame Rosenberg’s bedroom, for which Francis Picabia executed a series of Transparences, in which the contours and silhouettes of ancient figures were superimposed upon each other to create a beautiful but unstable palimpsest of mythological quotations. If the deities invoked in the titles and the metamorphic visual effects make one think of Ovid, Picabia’s paintings, according to co-curator Giovanni Casini, represent a deliberate emptying out of the classical tradition, voiding it of ideological substance to create a fluid repertoire of forms.

Combat (1928), Giorgio de Chirico. © ADAGP, Paris, 2023

If these large-format works make an immediate impact, the minor masters are just as powerful, whether in the audacity of their palette or the parodic glee of their compositions. Severini’s panels are a case in point: four of the original six produced for the bedroom of Rosenberg’s daughter Jacqueline, they juxtapose at disorientating scale and in technicolour hues the ruins of Roman monuments with the diversions of commedia dell’arte figures. Even stranger is the trio of works by Jean Viollier, a contributor to the Bulletin de l’Effort Moderne from 1925 whose art was shaped by Surrealism. In Viollier’s naive take on the Last Judgement, the familiar medieval iconography of Christ, saints and sinners is rendered camp by the addition of industrial machinery and a small figure peeping into view atop a ladder. Rosenberg’s taste cut across not just different French movements and tendencies – such as the Abstraction-Création of Albert Gleizes, the decorative panels of Fernand Léger and the allegories of Jean Metzinger – but also embraced many artists from further afield. He installed the cubist sculptures of the Armenian artist Yervand Kochar in the vestibule and asked Ecuadorian artist Manuel Rendón Seminario for nudes to decorate his bedroom.

Rosenberg did not have long to enjoy his creation, which was unveiled at a grand soirée in June 1929. Ruined by the Wall Street Crash, he was forced to move out of the apartment in 1932 and sell parts of his beloved collection. The curators have done a real service to art history by reuniting much of it for this exhibition, an eclectic, vibrant and ludic snapshot of French modern art at the crossroads.

Pavonia (1929), Francis Picabia. Musée Picasso, Paris. © ADAGP, Paris, 2024

‘Léonce Rosenberg’s apartment: De Chirico, Ernst, Léger, Picabia…’ at the Musée Picasso, Paris, until 19 May.