Since its inception, flash photography has been a subject of much interest to practitioners, especially to those usually (and derisively) called amateurs. Ever since Henri Cartier-Bresson disparaged the use of flash, it has held lingering negative associations for supposedly ‘serious’ photographers. Manuals advising on how to avoid those tell-tale reflections on shiny surfaces confirm the idea that the use of flash needs to be discreet if it is not to draw attention to its own vulgarity. The goal of flash technology for most of its users has been to make it possible to photograph subjects for which there is insufficient ambient lighting, and to do so in a way that makes itself as invisible as possible in the final product. Catering for this group, the literature on flash photography and its history (with some notable exceptions) has focused on technical advances that have made this goal possible.

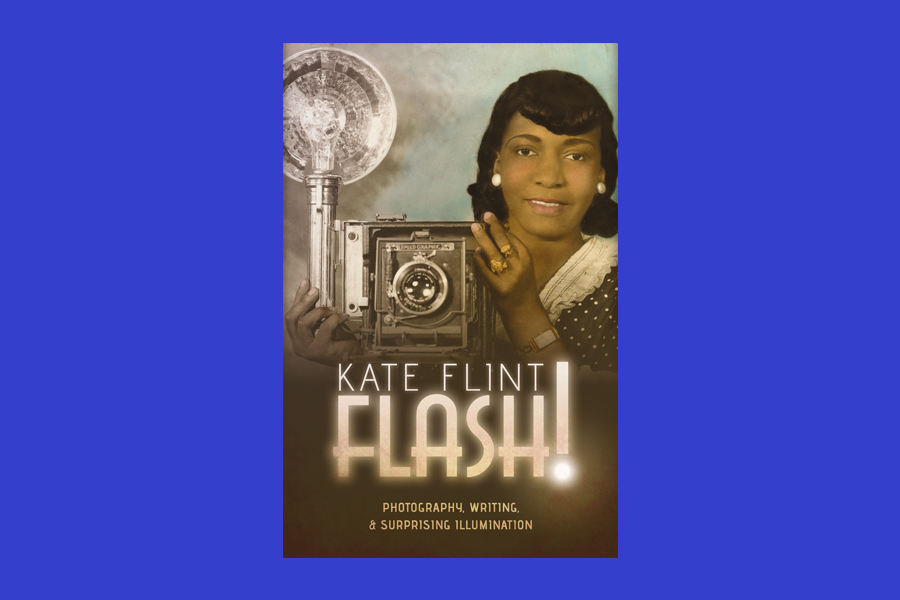

In Flash! Photography, Writing, & Surprising Illumination, Kate Flint approaches the subject rather differently. Looking less at photographs themselves and more at the discourse around flash (and its representations), Flint focuses on the experience of ‘flashing’, or being ‘flashed’, the distinctive features of the aesthetics of flash, and the cultural connotations of flash photography. Thus the cultural field is broadened out so that it covers not just specific technologies and the images they have helped to create – sometimes in unexpected contexts – but also the effects of those technologies and images on the imagination, on metaphor and on language. Some of this is more graspable instinctively than evidentially – a chapter on ‘flash memory’, for example, is suggestive rather than convincing. Sometimes, too, the range of metaphors and thematic associations take on a life of their own, leaving the reader far from the flash photography that is the book’s main thread – hence discussions, for instance, of the superhero Flash Gordon, of the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins and his use of the imagery of flashing foil, or of descriptions of nuclear explosions.

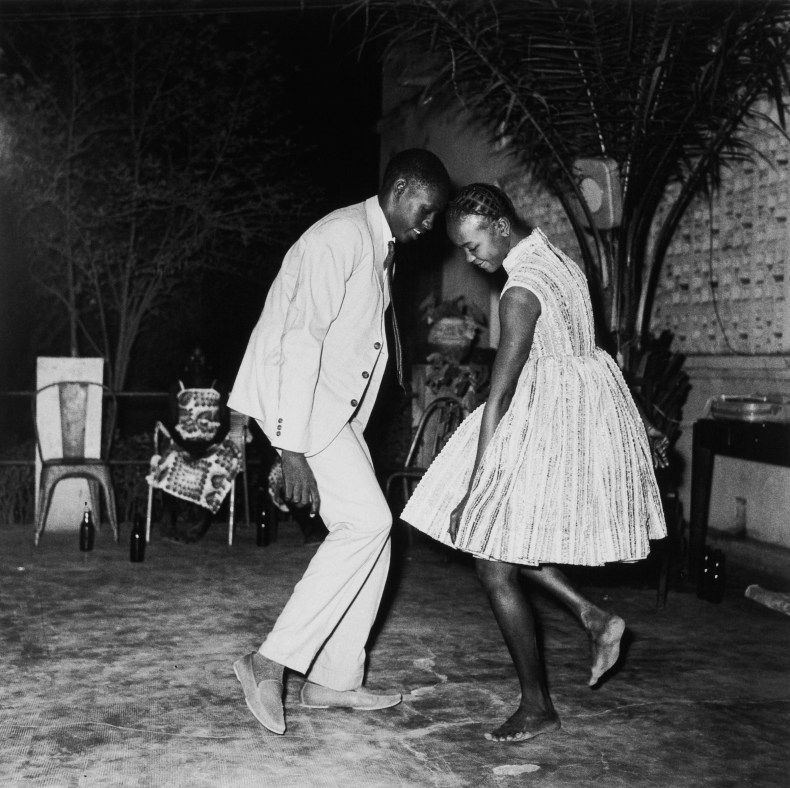

Nuit de Noel (Happy Club) (1963/2008), Malick Sidibé. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © Malick Sidibé

One effect, though, of Flint’s expanded field is to expose some unexpected constellations and intersections, notably that between flash photography and African American visibility. The book examines, for instance a magazine – also called Flash! – from the 1930s, which described itself as ‘a journal of negro affairs’. Flint shows how this publication harnessed the imagery of flash to further its end of highlighting African American contributions to public life, and also itself used flash photography to its own advantage in the representation of its readership.

Flash! also offers an opportunity to reflect on the various changing meanings of flash photography in an Anglo-American context, and how what had been an exciting (if dangerous) set of experiments, with analogies with the sublime effects of lightning, had become by the end of the 20th century a ubiquitous technology associated with the vapid glamour of celebrity and the intrusiveness of the news photographer. Weegee (Arthur Fellig) is the obvious point of reference here, and Flash! considers his role in the creation of flash photography’s lasting associations.

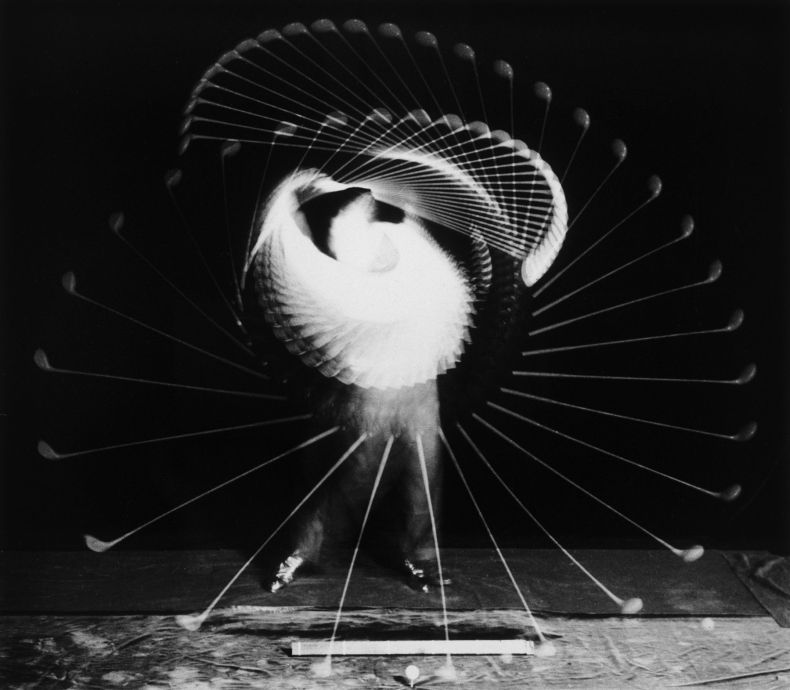

As Flint points out, Weegee’s work and persona were indivisible from developments in flash technology that coincided with his career. Flash! never ignores the changing technologies that underpin the cultural history that is its main subject. It pays close attention not only to enduring and commercially successful apparatuses like the flashbulb, but also to the many dead ends and short-lived solutions that litter the history of flash photography. This is a history – as Flint points out – of tinkering and improvisation as well as mass production, like the history of photography in general. At times a sort of hilarity breaks out in Flint’s narrative – perhaps inevitably, given the slapstick potential of flash powder delivered via a pistol, flares that routinely set fire to curtains and clothing, or smoke condensers made from old crinoline hoops. The levity has spread to the index, too, with the cute entry ‘cat, photographing a dropped’.

Bobby Jones with a Driver (1938), Dr Harold E. Edgerton. Bobby Jones with a Driver, (1938); © 2018 Estate of Harold E. Edgerton

It has to be said that Flash! is generically somewhat unstable. The book’s attention-grabbing title (the more complex subtitle is printed in tiny letters on the cover) and cheesy typography promise something which is slightly at odds with the author’s declared purpose, as though it cannot decide whether it is aimed at a general or an academic audience. The text itself adopts a more academic tone in some parts than in others, where it is padded out with large numbers of anecdotes that often seem to be repeated for effect rather than taking their place in the thread of an argument. Thus we hear how the contemporary Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto put up an altar in his darkroom to which he can pray ‘daily for trouble-free developing’; how an intrepid news reporter tried to photograph the Loch Ness Monster by night but got a photo of Boy Scouts instead when they set off his trip wires; or how Charles Bronson later regretted playing the lead role in the TV series Man With a Camera in the late 1950s when he realised (in his own words) that he was ‘playing second banana to a flash-bulb’ (the series was sponsored by a flash-bulb manufacturer).

Flash photography has its poignant and mysterious aspects, as Flint acknowledges, whether in the hands of an ‘amateur’ or an art photographer; but these are less well displayed in anecdotes or literary sources, and better embodied in the images themselves.

Flash! Photography, Writing, & Surprising Illumination by Kate Flint is published by Oxford University Press.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.