From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Sometime not long ago, before the pandemic rendered such gatherings unconscionable, I met up with a few fellow critics for drinks at a friend’s house. At one point in the evening, during a boisterous discussion about artists’ personal politics, someone casually remarked that so-and-so was ‘definitely a misogynist’, and everyone roundly agreed before cantering on with the conversation.

I didn’t catch the name of the artist to whom they were referring, except that it was that of a woman. The next day, I couldn’t stop wondering about the comment, and about the consensus that had immediately formed in the room. (All present were men.) Who was this well-known female misogynist? How and why did her irrefutable misogyny manifest? Consumed by curiosity, I emailed a friend to ask if he remembered who they were talking about. He told me it was Lisa Yuskavage. Many months later, when Yuskavage picks up the phone at her second home on the North Fork of Long Island, I still cannot decide whether to mention this story.

Though I was never sure how to pronounce her name (which is Lithuanian, and rhymes with ‘savage’), I have known Yuskavage’s paintings since the late 1990s, when the New York-based artist, now 58, was enjoying growing market success and not a little critical notoriety alongside other figurative artists such as Elizabeth Peyton, Rachel Feinstein, Cecily Brown, Inka Essenhigh and John Currin (the odd man out, as a man). Images of Yuskavage’s work often appeared in art-school lectures or books about the complicated condition of third-wave feminism, under the rubric of which heterosexual women were owning their sexuality in a manner once scorned by traditional, academic feminists, and were reclaiming language, imagery and stereotypes that had previously been considered demeaning.

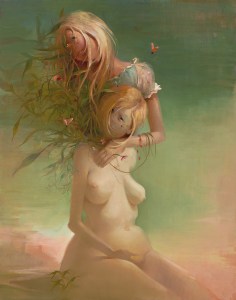

Kingdom (2005), Lisa Yuskavage. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Lisa Yuskavage

Yuskavage’s paintings, as you also probably know, almost always feature happily naked and amply proportioned female models, often with legs spread and nipples pointing upward at improbable angles. ‘Girls with women’s bodies […] women with girls’ faces,’ as Helen Molesworth puts it in the catalogue for the artist’s most recent museum show, ‘Wilderness’, which opened at the Aspen Art Museum last year and which travels in a modified form to the Baltimore Museum of Art next month (28 March–19 September). For many, Yuskavage will forever be the artist who used Bob Guccione’s 1970s Penthouse pin-ups as subjects for a series of paintings in the 1990s, devoid of the expected irony or political approbation.

‘I’ve always sensed that I’m the kind of artist that a lot of people think they know everything about,’ Yuskavage tells me. But even a cursory scan through three decades of her work reveals how limited such conceptions are. For a start, while the female figure dominates, by no means all are pictured in pornographic or even erotic contexts. Some, such as G. With Flowers (2003) or Kathy Draped (2001) or the recent The Psychic (2020), are naturalistic and tenderly handled portraits; others, like Rapture #2 (1993) or Manifest Destiny (1997–98), are fantastical and hyperbolic fabrications that outstrip George Condo or Robert Crumb. In the past three years or so, men have increasingly entered her compositions, as characters no less sympathetic and vivid than any of her women.

Rapture #2 (1993), Lisa Yuskavage. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Lisa Yuskavage

Two obvious challenges face any critic inclined to dismiss Yuskavage as misguided, misogynistic or somehow just plain bad. Firstly, there thrums an unmistakable fondness – admiration even – for the people in her pictures, even if she once described them as ‘half-retarded adolescents with their nipples popping out’. That’s just Lisa being Lisa, her friends would tell you. Whether drawn from life, or from found photographs, or from her imagination, you can see it in the realness of her characters’ faces, even at their most stylised; you see it in the glorious, proud beauty of their bodies, even as breasts sag or bellies swell more than the editors of Penthouse might have preferred. You see it in the seriousness and care with which she paints them: the gorgeousness of her colouration, her soft miasmas of light and her daring, taut compositions, as in the mysterious diptych Bonfire (2013–15). You see it most of all in the love – and there really is no better word for it – that the artist lavishes on every part of her canvas.

The second, closely related problem for naysayers is that Yuskavage is just so… good. If this sounds like an absurdly untenable judgement in today’s pluralistic art world, in her case it is as close to a solid fact as it is possible to get. She is a scrupulous student of her craft, researching source material deeply, working up preparatory drawings and paintings, and developing themes and motifs across multiple paintings. On her astoundingly exhaustive website, each work is cross-referenced with a handful of others, and tagged with a searchable taxonomy of categories and attributes.

Yuskavage is a painter’s painter, and a devotee of other painters, especially dead ones. Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini, Jacopo Tintoretto, J.M.W. Turner, Édouard Vuillard, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Philip Guston, even Marcel Duchamp, are just some of the countless artists whose lessons she has internalised. As ‘Wilderness’ co-curator Christopher Bedford has observed, Yuskavage deploys techniques such as sfumato – borrowed from Leonardo – in the interiors of her Northview series (1999–2005), and cangiantismo, developed by Michelangelo and widely used by Pontormo, in paintings such as Participants (2013) or Dude of Sorrows (2015). It is hard to avoid the sense that Yuskavage, in her seemingly boundless ambition, puts herself in competition with the Old Masters.

The Tongue Tondo (2018), Lisa Yuskavage. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Lisa Yuskavage

In conversation, Yuskavage can be both self-deprecating and assertive, circumspect and brassily unfiltered. When she first calls me, she’s out in the pitch-black Long Island night with her cockapoo. ‘Phillip, take a piss for God’s sake, it’s freezing out here!’ she yells at the dog, who is pickily selecting a spot to do his evening business.

She politely rejects my suggestion that what elevates her pictures of lowbrow subject matter is her masterful technique. ‘I actually think what makes me a good painter, if I am one – it’s not technical. Technical is all fine and good, but I think it’s the way that I construct a picture. The things that I do or do not put in it.’ Those decisions are made not via the hand, but in the mind; Yuskavage credits her analytical thinking in part to a 27-year course of therapy that she embarked on during a crisis early in her career, and which she ended just three years ago.

In 1990, four years out of her MFA at Yale, Yuskavage had her first New York show at Pamela Auchincloss Gallery, of paintings of abstracted female bodies retreating demurely into fields of rich colour. Outwardly, the exhibition appeared a huge success, but Yuskavage walked into her opening and realised she hated it. She sank into a deep depression and, for a while, gave up painting. She was saved by a therapist who was herself just completing her training, and so was very cheap. By talking analytically about herself, a couple of times a week, Yuskavage says, ‘I really hit on certain things. Part of what I understood was wrong, was how somehow at Yale, I became kind of embarrassed by my class.’ Having identified that embarrassment, she wrapped both arms around it, and did her utmost to replicate it for viewers of her paintings, regardless of their gender, sexual preference or background.

Taste, class and embarrassment remain central concerns within Yuskavage’s work. She grew up in Philadelphia, in the white working-class neighbourhood of Juniata Park. Her dad drove a truck delivering pies, and her mother was mainly a homemaker. They were supportive and proud, especially when she was accepted into the Tyler School of Art and then Yale. Yuskavage relates an anecdote from when her mother worked for a spell as a medical-records technician, and one day in the cafeteria pulled out a slide sheet of her daughter’s paintings, trying to encourage some of the doctors to buy them. Filling the awkward silence, her mother blurted out, ‘People think she was molested!’ Yuskavage continues: ‘Of course, Mom knows that I wasn’t molested, and she’s pretty certain that’s not the reason I was making the paintings, but they look at her and they say, “Actually that’s what I was thinking!”’

The Art Students (2017), Lisa Yuskavage. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Lisa Yuskavage

Why does Yuskavage make the paintings she does? It’s a question a friendly neighbour once asked her after innocently wandering into her studio. Yuskavage, flushed with embarrassment, couldn’t say. ‘I’m not gonna sit here and try to explain it because you’re gonna get bored.’ In most of her interviews she typically steers discussions towards how she makes her paintings rather than what she paints. ‘I don’t worry about it. I worry more about coming up with more interesting formal problems to solve. There is usually a thread that comes from earlier work. The work generates itself.’

Take, as an example, the painting that features on the cover of the catalogue for ‘Wilderness’. On a verdant plain, with mountains in the far distance, a young girl lies on her tummy, sucking contemplatively on a red lollipop, raising her splayed legs so the gusset of her blue panties is framed by her stripey socks. It is actually the left panel of a very large work, Triptych (2010–11), which began life as a study titled Safety Orange (2010), just 20cm wide. The tiny painting begat a large painting. Then Yuskavage heard a voice in her head: ‘There is more.’ Uh oh, she thought.

Triptych (2010–11), Lisa Yuskavage. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Lisa Yuskavage

The canvas ended up as part of a triptych well over five metres across. The central panel is dominated by a woman on her back; her head hidden, we see only the V of her raised legs and, between them, her vagina. (Duchamp’s Étant donnés, 1946–66, to which this figure so clearly alludes, is one of the first artworks Yuskavage ever saw.) If, as Yuskavage suggests, this is the id, and the lollipop-sucker the ego, then to the right appears the superego: on a distant hill, in long skirts and headscarves, unsmiling peasant women look on with hands clasped. These figures, which reappear in other paintings, are what Yuskavage latterly came to call her ‘Nel’zahs’. The name was suggested by her husband, the painter Matvey Levenstein, who recalled the ‘old babushka ladies with slippers on’ they encountered on their honeymoon to Russia, in 1992. ‘Nel’zah!’ Yuskavage was always being told, especially in museums, especially when she peered too closely at paintings. Usually she just smiled, confused, with her bright white American smile. She asked Levenstein, who was born in Moscow, what the phrase meant. ‘Just don’t!’ was his best translation.

‘I’ve felt it all my life,’ Yuskavage says, ‘whether it’s just my own personality or because I’m a woman or because I am an aspiring working-class person trying to get into the fancy art world or whatever, it’s just this kind of getting knocked back with the chorus of “nos”. But not willing to really heed them.’

I never muster the courage to ask Yuskavage if she’s a misogynist. The question seems so flat-footed after consideration of the artist’s subtle, intelligent and irresolvably complicated paintings. It would feel gauche, in bad taste. And anyway, she’s freely admitted as much in the past. In an interview with the painter Chuck Close in 1996, she said: ‘I have no interest in pointing the finger anywhere but at myself, and telling about my crimes. I am interested in making work about how things are rather than how they should be. I exploit what’s dangerous and what scares me about myself: misogyny, self-deprecation, social climbing, the constant longing for perfection.’

Certainly, both the artist and viewer are ensnared in whatever toxicity is implied in her subjects, but also, maybe, emancipated through Yuskavage’s treatment of them. ‘I don’t work from an elevated place looking down,’ she said in an interview in 2000. ‘If they are low, then I am in the ditch with them, and by painting them, trying to dig us out together.’

Might any of Yuskavage’s pictures be considered self-portraits? The question is not easily answered, even if she has, in the past, emphasised the gulf of difference, physical and otherwise, between herself and her subjects. And yet. It is often mentioned that Yuskavage worked as a life model while in art school. To my knowledge, she has only ever painted white women, because, I assume, she herself is white. Even if they are not her, exactly, they are her people, her kin.

Self Portrait (2017), Lisa Yuskavage. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Lisa Yuskavage

I ask about a painting from 2017, Self Portrait. A dark-haired nude woman poses in front of a camera on a tripod; looming behind her, ethereal but giant, is a man, also nude, his hands on her waist. Yuskavage is momentarily thrown by my reference to the painting, and then explains apologetically that she named it ‘on the fly’. The title is, in fact, brilliantly clever. The source image is from of a trove of slides Yuskavage acquired from Bob Guccione’s private collection. She professes a fascination for Guccione, who, she says, was a sophisticated photographer who understood light and reflection through studying paintings by Vermeer. ‘Nobody’s willing to talk about this because the high-lowness of this is so fucked up!’ she says. ‘If I was going to be Andrea Dworkin, I would say this was really bad for women. I just don’t make art thinking about what’s good for anybody or bad for anybody.’

Yuskavage discovered that in certain shoots, Guccione would photograph himself with his models. ‘He couldn’t help but put himself in the picture,’ she says. These unpublished slides set her thinking about her own authorship. On Self Portrait, which features a model named Lavinia, Yuskavage muses, ‘I’m the camera, I’m the paint, I’m the light, I’m Bob, I’m Lavinia, I’m all of them, I’m none of them. It’s a dream. It’s a painting. It’s all the same.’

Whether you think you like Yuskavage’s work or not, to take it seriously is to challenge profoundly one’s own preconceptions about the value of art, and the role and responsibility of the artist. What freedoms does the artist deserve? What personal virtues do we demand of her? And, by the way, since when was being an artist about being right or wrong? The more I spend time with Yuskavage’s painting, the more I feel exasperated by the contemporary art world, with its sanctimonious critical judgements based on banal moral orthodoxies. I don’t want what is good for me. And I don’t care about being right.

‘Lisa Yuskavage: Wilderness’ is at Baltimore Museum of Art from 28 March–19 September.

From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.