A streak of light stealing through a crack beneath a closed door. Tadpole-like raindrops wriggling down four window panes. Lois Dodd’s paintings, which capture the ordinary in an extraordinary way, are currently on view in a small exhibition at Modern Art in east London – the artist’s first survey outside the US.

New Jersey-born Dodd has lived and worked on the East Coast for the past 70 years. She studied textile design at Cooper Union from 1945 to 1948, after which she spent a year doing a little painting – but mostly ‘looking at other art’ – in Italy. Upon her return she co-founded an artist-run space on 10th Street called Tanager Gallery, which was frequented by figures such as Alex Katz and Willem de Kooning. It was during this time – while the art world was swinging towards the gestural marks and colour fields of New York’s Abstract Expressionists – that she shifted her attention entirely to painting, albeit in a very different style.

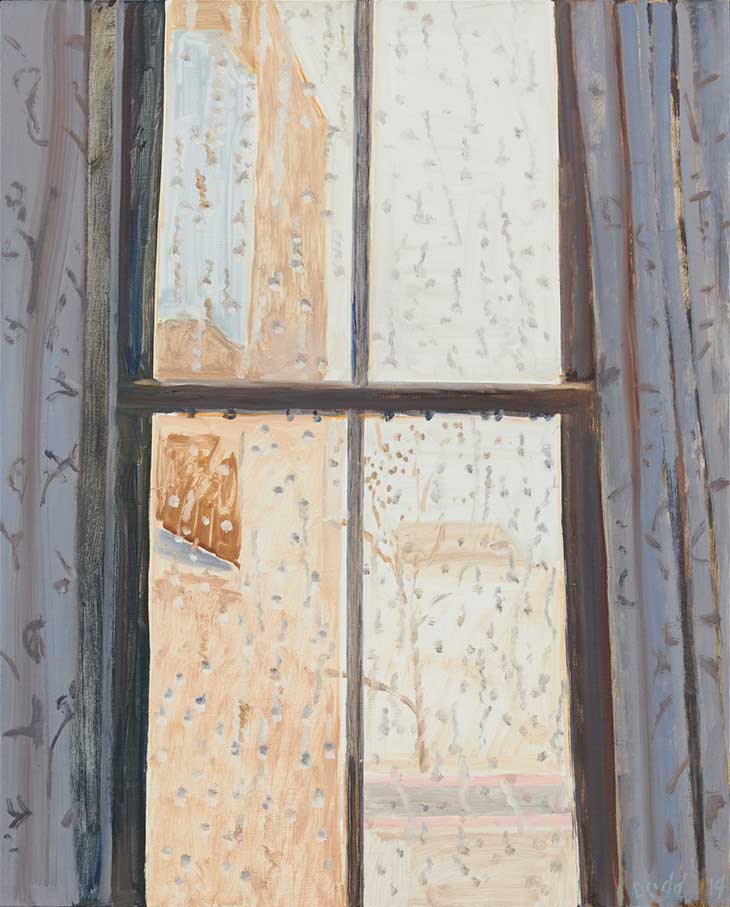

Rainy Window, NYC (2014), Lois Dodd. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy Modern Art, London and Alexandre Gallery, New York; © Lois Dodd

In the summer of 1951 Dodd made her first visit to Maine with Katz, from whom she learned to paint en plein air. Together with him and his first wife, Jean Cohen, Dodd and her then-husband, the sculptor Bill King, bought a house on the coast. In her paintings, she began to capture the surrounding woodland and vernacular architecture – clapboard houses and barns with dormers and sash windows. When Katz and his second wife, Ada, bought her out in 1964, she acquired her own place in Cushing, a seaside town an hour or so’s drive to the south.

Standing Swimmer (1966), Lois Dodd. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy Modern Art, London and Alexandre Gallery, New York; © Lois Dodd

Standing Swimmer (1966) is the earliest of Dodd’s 20 works on show at Modern Art, and it’s markedly different from the rest. A mass of fertile green and saffron yellow stretches across the canvas, which centres on a nude with jelly-like flesh and outstretched arms – on the brink of a dive, perhaps. Dodd created it during a brief period that veered towards pure abstraction. Squint and the swimmer merges with the shapeless forms around her, part of a patchwork landscape.

The show picks up again a decade later, by which time Dodd had found her style – a flat figuration achieved through thinly applied paint. She moved away from depicting people and yet – like Edward Hopper’s freshly vacated paintings – almost every work reveals a trace of life. Washing has been hung out to dry in Red Curtains and Lace Plant (1978), while someone has left the door ajar in Front Door Cushing (1982). Stare for long enough at Headlights and Hillside (1992) and you’ll find yourself wincing in anticipation of a startled bunny leaping out in front of a car. A figure does appear in Burning House, Night, with Fireman (2007), which features a firefighter with a hose. But our hero blurs seamlessly, unheroically, into the background as the licking flames – a riot of lavender, rusty orange and yellow – steal the show.

Red Curtains and Lace Plant (1978), Lois Dodd. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy Modern Art, London and Alexandre Gallery, New York; © Lois Dodd

Dodd’s paintings pay homage to the elements, framing them through an open door or in a pane of glass. Three-quarters of the canvas in Front Door Cushing is taken up by a pared-back greyish-blue interior, but it’s the wedge of expressionistic zingy green foliage outside that garners our attention. In Falling Window Sash (1992) the muddy-green clapboard is offset by flashes of blue sky reflected among leafy branches in the glass, the frame of which echoes the edges of the canvas. There’s a sense of voyeurism here, as in Dodd’s other window paintings, our eyes straining for a sneak peek of a private life. But Dodd keeps us guessing. There may be a light left glowing in one of the rooms of the houses she paints against an inky night sky, but that’s all you can see – a small slice of yellow-white. Though true-to-life observations, Dodd’s paintings are far from illusionistic. She reels us in with what appears to be a flawless finish, then shakes things up with a conspicuous mark. A daub of greenish-black on a lemony petal of the otherwise unblemished Yellow Iris (2006), for example, and the marks of a bristle brush in Blue Bottle and House Eve (2016).

Front Door Cushing (1982), Lois Dodd. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy Modern Art, London and Alexandre Gallery, New York; © Lois Dodd

Now aged 92, Dodd continues to document both the natural and man-made world around her, from those clapboard houses in Cushing to the Delaware River in New Jersey and urban details scavenged from Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She had her first museum retrospective just seven years ago – a show that opened in Kansas City then travelled to Maine – and this survey at Modern Art introduces her to a new audience across the pond. Lucky for us, because we could all do with a little of her world in our lives – clean-cut and candid, filter-free. In paint Dodd encourages an appreciation of the everyday because, as she once remarked, ‘it’s such a kick, really, seeing things’.

‘Lois Dodd’ is at Modern Art, London, until 24 August.