This jaw-dropping panoply of the American commercial press is from the collection of one man, Steven Lomazow, M.D., amassed over the last 40 years and focuses particularly on early American magazines, and the teens, twenties and thirties of the 20th century. It’s not just collecting – it’s securing Volume 1, Number 1 of practically every magazine, noteworthy or crazy, that ever appeared on North American soil. The New England Journal of Medicine, Scientific American, the New Yorker, Mad, Ms., Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly and the beautiful Holiday. Artists include Maxfield Parrish, Howard Chandler Christie, Charles Dana Gibson and even Alberto Vargas. The first American magazines appeared in 1741. By 1860 there were over a thousand titles in print, ballyhooing and cajoling Americans to repent, reform, learn, expand, and do everything faster and faster. The amazing energy of the United States is all here – educationalism, advertising, news, religion and quite a lot of hooey. As is pointed out in the excellent catalogue, magazines built American communities, and fashioned their mores and prejudices.

The deadly serious early journals have a grand, reserved, essentially European look: mournful engraved figures adorn their covers, as if weighed down by the awful information inside. The Mystery of Living (‘Health, Wealth, Time and Morals’) – could anything better sum up the American 19th century? Its cover is gladdened by a tidy woman at a simmering stove, surrounded with flowers, vegetables, numerous dead animals, a very large trout and some lobsters. Truly, the way forward was to be found in these pages. Information often came wrapped in the flag, accompanied by allegorical figures, decorative young ladies, or eagles. On the cover of Lady’s Magazine: and Repository of Entertaining Knowledge, the ‘genius’ of the magazine is shown giving Liberty a copy of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

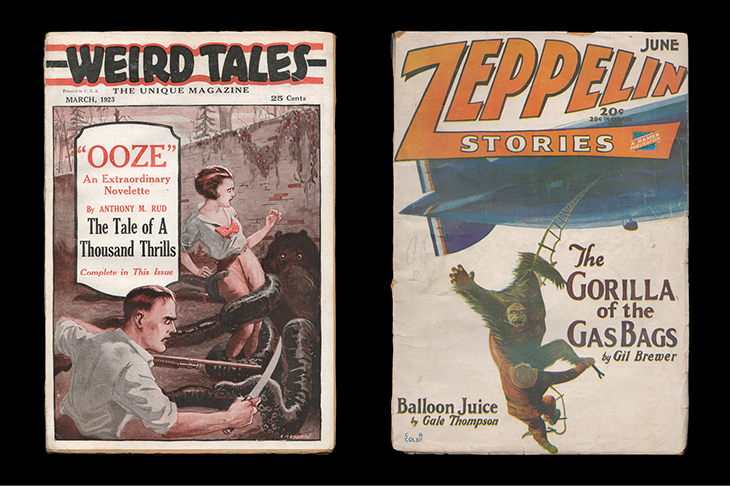

Left: Weird Tales: The Unique Magazine, vol. 1, no. 1, March 1923. The best-known fantasy and horror magazine during the golden age of pulps; right: Zeppelin Stories, vol. 1, no. 3, January 1929. Collection of Steven Lomazow

Entertainment became big business with pulp magazines devoted to crime, science fiction, westerns and general seething salaciousness. Black Mask, probably the most renowned pulp of them all, offers Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon complete. There’s a lovely copy of Weird Tales, one of the most successful lurid pulps, featuring a story called ‘Ooze’, which would no doubt repay study (the fact that you can’t just grab these magazines and start reading them might drive you crazy). A kind of bear-octopus has got hold of a girl and her handy fella’s trying to kill it with a rifle and a sword at the same time. Palmy days.

Publications for children began early in American periodical history (with Little-Pig Monthly), and – gulp – here is the first issue of the ubiquitous and demoralising Highlights for Children. Its slogan, ‘Fun with a Purpose’, is a phrase to make any eight-year-old shudder. This fabulously stupid and annoying magazine made every trip to the dentist doubly awful.

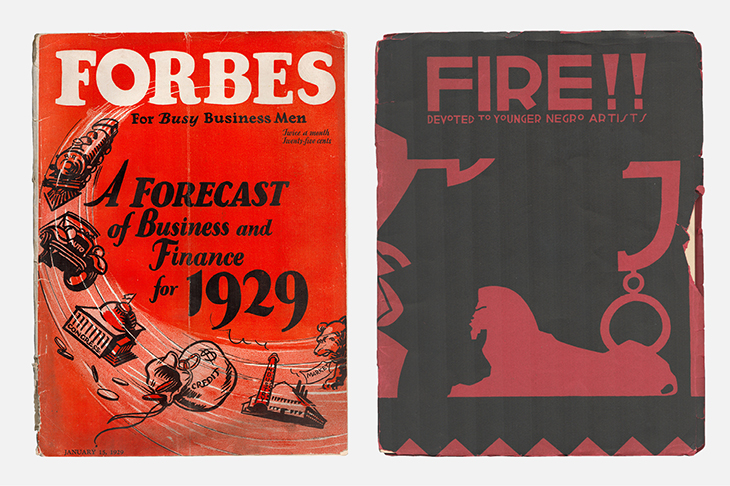

Left: Forbes, vol. 23, no. 11, January 15, 1929. In January 1929, Forbes predicted a banner year for the stock market; right: Fire!!: A Quarterly Devoted to Younger Negro Artists, vol. 1, no. 1, November 1926. Collection of Steven Lomazow

Here too is the history of the African-American press. The Crisis, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois, still thrives today. There also was Fire, an organ for young Black artists with contributions from pretty much everybody in Harlem. And as Black American life became, in some senses, richer, magazines of popular interest and even tittle-tattle appeared: Ebony, cornerstone of the giant Johnson Publications empire; Bronze Thrills and Tan Confessions.

There were parallel worlds of magazines, notably among the marginalised. There were magazines for mill girls, flappers, and several for hobos, one exhorting them to buy war bonds. Temperance publications abounded, from the beginning of the republic (The Cold Water Magazine), but later there was Repeal, decorated with the Liberty Bell, fighting for all who wanted beer. There was at least one periodical given over to fiction about zeppelins.

Left: The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races, vol. 49, no. 4, April 1942; right: Douglas Airview, vol. 13, no. 1, January 1946. The cover contains the first published image of Norma Jean Dougherty, later known as Marilyn Monroe. Collection of Steven Lomazow

Inside an issue of the Pennsylvania Magazine of 1776: the only magazine publication of the Declaration of Independence. The Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage, a pretty sober-looking little thing of 1855, printed, for the very first time, the rules of ‘base ball’. Seems simple enough. How about Douglas Airview, a journal devoted to post-war commercial aviation, the duty of getting yourself on a plane? Here they are, these dressed-up 1946-type people, relaxed and actually happy, flying. You wouldn’t believe the leg room. The Berkeley Barb was perhaps the most influential of all the counterculture press in the San Francisco Bay Area of the 1960s. We used to read it for the ‘Dr HipPocrates’ column– a real education in the effects (we hoped) of free love and LSD.

Left: Repeal: A Monthly Magazine Devoted to National Prohibition Reform, vol. 1, no. 1, September 1931; right: Mother Earth, vol. 1, no. 1, March 1906. An anarchist literary and political monthly edited by Emma Goldman. Collection of Steven Lomazow

On the cover of Emma Goldman’s magazine, Mother Earth, a naked couple lean against a tree. At its roots lie a number of broken shackles. The man holds out his hands to the coming dawn. What’s the matter with that? But for wanting to emancipate people and resist war, Emma Goldman was stripped of her US citizenship and deported.

Americans used to hunger for information and knowledge. To think of all these magazines whirling across the country and into the mailboxes of farmers, teachers, inventors, children, housewives, cooks, fly-fishermen and baseball fans for 200 years… Now all they have is the internet. What happened to American progressivism, once envisioned and proselytised with all this insight, grace and gusto?

‘Magazines and the American Experience: Highlights from the Collection of Steven Lomazow, M.D.’ is at the Grolier Club, New York, until 24 April.