British art after Brexit | More peculiar timing for a sale devoted to British art is hard to imagine. Christie’s 250th anniversary ‘Defining British Art’ evening sale took place on 30 June, when the whole nation was still struggling to define what it was.

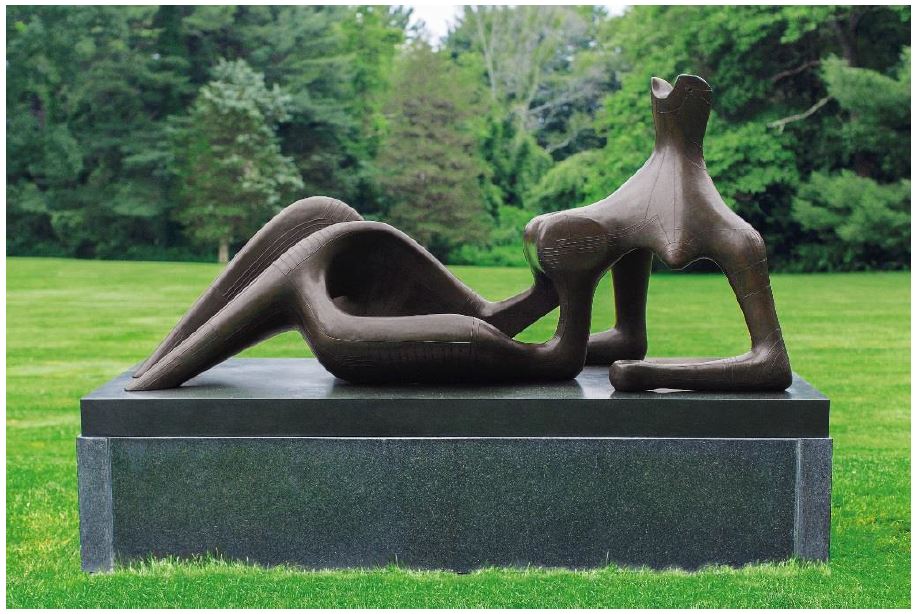

At the sale, which spanned four centuries of British art from Stubbs to Bacon, bidding felt as unpredictable as a day in British politics. In keeping with market demand, one might have expected post-war and contemporary works to fare better than older pieces. Yet the top 10 results included works dating from 1778 to 1968, led by a record price for Henry Moore, whose monumental Reclining Figure: Festival fetched £24.7 million. Lucian Freud’s Ib and her Husband unexpectedly failed to sell at £16 million, while determined bidding on a 1950s Alfred Munnings of H.M. the Queen and Aureole in the Paddock at Epsom before the Coronation Cup surprised the room. It sold at £2.1 million, aided by its regal subject.

Reclining Figure: Festival , by Henry Moore, fetched £24.7 million at Christie’s. © Susan Young

A cautious atmosphere belied a solid sale, with 87 per cent of 31 lots sold and eight auction records set – for Frank Auerbach, Lynn Chadwick, Frederic Lord Leighton, Henry Moore, Samuel John Peploe, Bridget Riley, David Roberts, and Thomas Daniell. The £99.5 million total was the highest of the week and would, conceded Jussi Pylkkänen, Christie’s Global President, ‘probably never happen again in a British art sale’. He thought it ‘an indicator the market has really found its feet’ after Brexit.

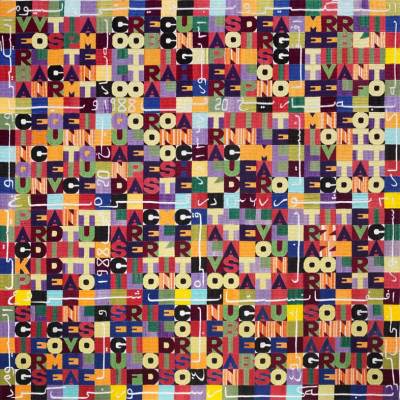

The sale saw bidders from 32 countries, and strong Asian interest. Elaine Holt of Christie’s Hong Kong bought Auerbach’s Head of Leon Kossoff (for a record £2.66 million) and Study for a Tree on Primrose Hill (£566,500) and Riley’s Untitled (Diagonal Curve) (£4.3 million). Seven lots were subject to third-party guarantees, among them Constable’s View on the Stour near Dedham (sold at £14.1 million, though with only two bids). Five of the guarantees had been negotiated in the past three weeks, since the catalogue went to press, as vendors grew understandably nervous; many had been persuaded to consign by the one-off nature of the sale.

Helena Newman headed the Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Sale on 21 June – but there were no works by women artists in the sale.

Women on the rise | On 21 June Helena Newman became the first woman to take a London evening auction since Melanie Clore in 1990, at Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern sale. Yet it included no works by female artists. A boost for women artists came in the same room a week later, however, at the auction house’s contemporary evening sale, when Jenny Saville’s Shift (1996–97) soared over a £1.5–2 million estimate to sell at £6.8 million – a record for any British female artist at auction. This gargantuan painting, exhibited in ‘Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection’ in 1997, was bought by Liu Yiqian and his wife, Wang Wei, of Shanghai’s Long Museum. The Saville will be the centrepiece of the museum’s upcoming ‘She’ exhibition of women artists. As one observer quipped, the couple seems to ‘hold up the art market at the moment’.

Jenny Saville’s Shift (pictured, right) fetched £6.6 million (with fees) at Sotheby’s contemporary sale last night. Photo: Sotheby’s

Cautious optimism | Auctions can by turns be sharply affected by wider events or exist in a surreal bubble: the latter was true of the Sotheby’s sale, which demonstrated how the top end of the market can march on, apparently unscathed by domestic politics and economic uncertainty. Its success was a tonic to the preview opening of the Masterpiece London fair the following day (until 6 July) where exhibitors and visitors dusted themselves down after the shock of Friday’s referendum result and were in rosy mood.

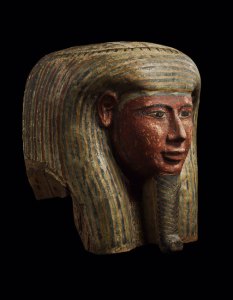

Mummy Mask from Western Thebes (c. 760–525), was sold for $500,000 at Masterpiece London. Courtesy of Ariadne Galleries

‘There’s an optimism,’ said Andrew Duncanson of Stockholm design gallery Modernity, whose numerous sales included a 1920s long case clock by Jens Jakob Bregnø for £100,000. ‘We’re already seeing the effects of the pound’s collapse against the dollar; more Americans are buying.’ Other early sales included Ariadne Galleries’ Egyptian Mummy Mask, Late Period (c. 664–525 BC), for $500,000 US dollars.

‘Maybe it’s that old adage that when things are uncertain, people see art as a refuge for cash,’ Emma Ward of London dealer Dickinson observed. New York-based art adviser Mary Hoeveler echoed the thought: ‘People seem to seek the art market in times of instability. The question is what will happen long term for Britain as the art centre of Europe with importation and taxes. I’ve heard convincing arguments both for and against.’

A new arrival in London | After months of speculation, Salzburg and Paris contemporary art dealer Thaddaeus Ropac has confirmed his purchase of Ely House on Dover Street, Mayfair, former home of antiques dealership Mallett. The Stanley Gibbons Group, Mallett’s parent company, sold its lease of the five-storey 18th-century building along with an adjacent property for £2.5 million in May. Ropac’s gallery will open in spring 2017 in the former Bishop’s Palace, after a ‘sensitive’ renovation by New York architect Annabelle Selldorf. It will be led by Polly Robinson Gaer, who joined Ropac from Pace last year. Pre-empting Brexit questions, Ropac said he had ‘no doubt that London will continue to be one of the most vibrant and quintessential art centres in the world’. Quietly impressive, the discreet Mayfair townhouse has become an object of desire for top-rung international contemporary art galleries. Michael Werner and David Zwirner’s premises are a case in point. Could a trophy staircase be the new street frontage?

Mayfair courts new visitors | It is the season for London art galleries to be at their most welcoming as London Art Week (until 8 July) and Brown’s London Art Weekend (1–3 July) hope to tempt newcomers and established clients alike past the buzzer. The longer established, Old-Master-focused London Art Week features concurrent exhibitions throughout Mayfair and St James’s, including Agnew’s focus on The Crucifixion by Paolo Uccello and the Weiss Gallery’s 30th anniversary exhibition of Cornelius Johnson. Brown’s London Art Weekend extends to contemporary galleries, has more participants (some but not all are involved with LAW too) and is more event-focused – think gallery tours and talks, such as Abby Hignell and Maeve Doyle’s ‘Women in the arts’ tour and champagne brunch on Saturday 2 July (12–3pm).