Digby Warde-Aldam surveys the London art scene…

Now that we are gearing up for the General Election – and may well be in for a coalition with the Scottish nationalists – the ugly question of ‘English Identity’ has raised its head once more. Implicit in this fatuous argument is the idea that the English regions have a culture with a capital ‘C’ that is implicitly separate from that of the Welsh, the Northern Irish and the Scots. Nonsense. But if we do, what is this august tradition? Is it John Major’s ‘long shadows on cricket grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs’. Not for me, thanks.

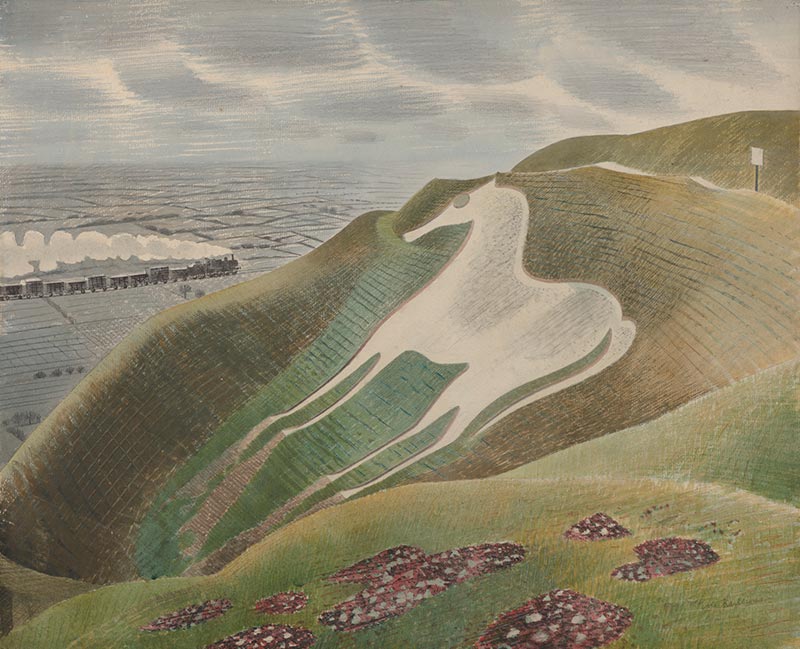

As for art, our painters have traditionally looked beyond these shores for inspiration. Looking at the work a lot of England’s greatest artists – Turner springs to mind – you often get the sense that they wished they were elsewhere. To be brutally honest, the English landscape can’t really compete with France and Italy in the romantic excitement stakes, and it takes an imaginative painter to celebrate rural England without coming across as parochial. But for an all too brief period, Eric Ravilious was just such a painter.

God, could Ravilious paint. With his deceptively unconfrontational paintings, he captured the polite but unignorable weirdness of this country. He was a surrealist without needing to resort to surrealism. The mad landscape and contemporary possibilities England afforded him were ammunition enough. He depicted scenes that other painters wouldn’t have given the time of day, noticing the strangeness and beauty of everyday objects and views that others wouldn’t give the time of day. You can see this bonkers, brilliant and utterly unique vision of this country on show at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (until 31 August), and I strongly urge you to do so.

Ravilious’s view of England made me long to take a train journey out of London. So I stole an afternoon and headed to the Fry Gallery in Saffron Walden to see a show by one of his students, Kenneth Rowntree (until 25 October). Rowntree’s early paintings are exciting, to be sure – even in his most conventional work, his use of perspective is unexpected and often dizzying. But it was only when he was appointed Professor of Fine Art at Newcastle University (and thus, a colleague of Richard Hamilton) that he really escaped the shadow of his tragically-deceased tutor. From the late ‘50s onward, Rowntree was on fire, dipping into modernism without ever bowing to faddishness.

Ravilious’s view of England made me long to take a train journey out of London. So I stole an afternoon and headed to the Fry Gallery in Saffron Walden to see a show by one of his students, Kenneth Rowntree (until 25 October). Rowntree’s early paintings are exciting, to be sure – even in his most conventional work, his use of perspective is unexpected and often dizzying. But it was only when he was appointed Professor of Fine Art at Newcastle University (and thus, a colleague of Richard Hamilton) that he really escaped the shadow of his tragically-deceased tutor. From the late ‘50s onward, Rowntree was on fire, dipping into modernism without ever bowing to faddishness.

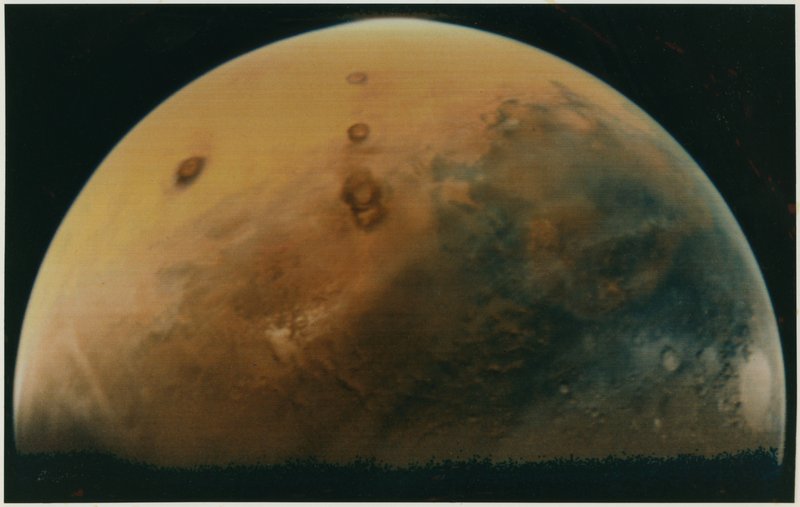

The trip made me wish I could get out a bit more. I’m currently stuck at my desk, and my confinement is such that, when I got the slow train out to Hoxton to Daniel Blau’s gallery last week, I felt like an astronaut taking a first spacewalk from a shuttle. Not inappropriate, given the exhibition’s subject matter.

The current show (until 15 May) presents a revelatory selection of colour images of the USA’s first forays into Space. They give an idea of quite how precarious these adventures were: the astronauts and their equipment look fragile, and their spacecraft rudimentary. One of the earliest pictures here, from 1965, shows the blue curve of the Earth, foregrounded by astronaut Ed White clutching a camera as he floats outside Gemini 4. I stared, and got a sudden hit of vertigo. Go. You’ll be starstruck.

Coming back to Earth, I was invited to a press screening of a film called Woman in Gold, in which Helen Mirren plays Maria Altmann, an Austrian Jewish woman whose family were the original owners of Gustav Klimt’s masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, a painting looted by the Nazis. The film tells the story of Altmann’s extraordinary battle to claim it back from Vienna’s Galerie Belvedere, where it ended up after the war.

Coming back to Earth, I was invited to a press screening of a film called Woman in Gold, in which Helen Mirren plays Maria Altmann, an Austrian Jewish woman whose family were the original owners of Gustav Klimt’s masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, a painting looted by the Nazis. The film tells the story of Altmann’s extraordinary battle to claim it back from Vienna’s Galerie Belvedere, where it ended up after the war.

I’ll be honest with you: it really isn’t very good. Helen Mirren’s Mitteleuropean accent would’ve been rejected by the producers of ‘Allo ‘Allo! as too camp. I winced at actor Ryan Reynolds’s portrayal of Altmann’s lawyer – he looks awkward trying to play ‘awkward’, which, perversely, is about as convincing as Cecilia Gimenez’s ‘restoration’ of that Jesus fresco. The staff of the Galerie Belvedere, meanwhile, are shown as cackling pantomime villains, as morally defunct as the Nazi goons who confiscated the painting in the first place.

So, nuanced it isn’t. But more perversely still, I actually rather enjoyed it. Watching really terrible films for free is one of life’s stranger pleasures. And for all its failures, Woman in Gold keeps the own-brand suspense consistent throughout. If you see the DVD in a charity shop, pay no less than 48p.

Related Articles

Small Wonders: The Fry Art Gallery