It is 16 years since Frieze burst on to the London art scene, grabbing the attention of the international art world and spawning a galaxy of satellite fairs, shows and other events, including its own progeny, Frieze Masters. New to this year’s main edition is a themed gallery section focusing on the legacy of radical feminist artists and the galleries that supported them, curated by Alison Gingeras, a supplement to Frieze’s classic mix of emerging gallerists and artists alongside the lions of the contemporary art business. Judging by the line-up of the latter, all bodes well for Regent’s Park this autumn (5–8 October).

As would be expected, several gallerists show work by artists currently in the spotlight – from Alicja Kwade, wreathed in glory after the Venice Biennale (kamel mennour), to the Unfinished Installation by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, courtesy of Sprovieri. There is also a less expected whiff of Venice and Damien Hirst’s ‘Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable’ – and indeed the Royal Academy’s 2012 survey ‘Bronze’ – about Hauser & Wirth’s thematic offering: ‘Bronze Age c. 3500 BC–AD 2017’. This ‘faux’ presentation juxtaposes artefacts on loan from UK museums and private collections with ‘ancient’ pieces, many of them purchased from eBay, as well as bronzes by the likes of Fausto Melotti, David Smith, Marcel Duchamp, and Subodh Gupta.

Invariably, Frieze Week auctions see many of the biggest sales. Christie’s London’s Post War and Contemporary Art evening auction on 6 October features a concentration of British painting and a group of artists who helped revive a medium long declared dead. Offered here is Peter Doig’s characteristically brooding, dreamlike Camp Forestia of 1996, in which a Canadian log cabin gleams against a starry, inky sky and its uncannily perfect reflection in the still waters of the lake below is separated by a line of snow-covered, lime green grass and a small human figure (estimate: £14m–£18m). There are figures and reflections, too, in the icy Mount Royal (Lac des Castors) painted in 1998 by Hurvin Anderson, Doig’s pupil at the Royal College of Art. Inspired by a photograph sent home by the artist’s sister who had emigrated to Canada, it shares qualities of memory and displacement (estimate: £400,000–£600,000).

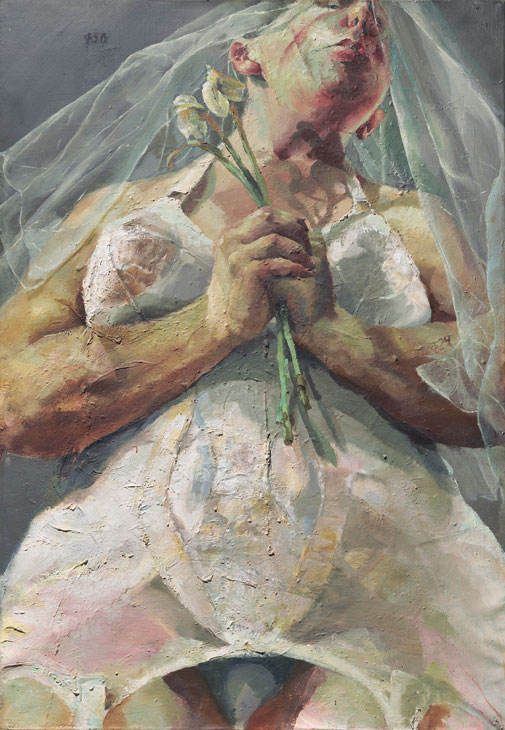

The Bride (1992), Jenny Saville. Christie’s London (£1m–£1.5m). Christie’s Images Ltd 2017

Jenny Saville’s The Bride was also painted during her final year, at the Glasgow School of Art in 1992. After her graduation show, every work on display was tracked down and bought by Charles Saatchi who offered her an 18-month contract and exhibition. Great mounds of female flesh compressed into picture planes that barely confine their bulk dominate these early paintings but, as the artist once said, it is the neuroses bursting through the ample folds that interest her. ‘I’m interested in the physical power a large female body has – a body that occupies a lot of physical space, but also someone who’s acutely aware that our contemporary culture encourages her to disguise her bulk and look as small as possible.’

Although far from obese – unlike most of Saville’s subjects – this bride is still full of a visceral, painful self-loathing as she stands apparently inspecting herself in her substantial corsetry. The paint surface is almost sculptural in its lush impasto and creates a beauty at odds with its theoretically ugly subject matter. Last June at Sotheby’s London, Shift, the artist’s painting of monumental nudes of 1996–97, sold to the prominent Chinese collector Wang Wei for a record £6.8m. This canvas comes to Christie’s London with expectations of £1m–£1.5m.

In the final phase of his career, Philip Guston, once described as the ‘high priest of the abstract expressionist painting cult’, returned, outrageously, to representation. It was a treachery akin to Picasso’s move from the elegant realism of the Rose period to analytical Cubism, which Apollinaire memorably described as ‘carrying out his own assassination with the practised and methodical hand of a great surgeon’. For Guston, American abstract art had become a lie, ‘a sham, a cover-up for a poverty of spirit. A mask to mask the fear of revealing oneself’. After this change of heart around 1968, however, his vocabulary might have become cartoonish and explicit but its meaning remained enigmatic.

Odessa (1977), Philip Guston. Sotheby’s London (£2.5m–£3.5m). Image courtesy Sotheby’s

Certainly the meaning of Odessa (1977) is far from apparent. Its subject resembles a monolithic temple of a structure apparently emerging from the sea, its squat columns like hairy legs, its lintels the soles of solid, heavy boots. Is this a nostalgic, symbolic reimagining of the Russian city from which his parents had fled, a homeland and refuge he never had, or an allusion to the neat piles of boots stacked in Nazi concentration camps? The auction record for Guston, the abstract work To Fellini (1958), stands at $25.9m. Odessa, offered at Sotheby’s London’s 5 October Contemporary Art evening sale, is estimated at £2.5m–£3.5m.

Not all the best items are to be found in London. Cheffins of Cambridge offers two signed and previously unrecorded pencil drawings by Alberto Giacometti. This double-sided sheet, authenticated by the Fondation Giacometti, presents studies of four heads on the recto and a standing female nude on the verso. They belonged to the splendid antiques dealer Eila Grahame whose Kensington Church Street shop always offered the unexpected (12 October; estimate £40,000–£60,000).

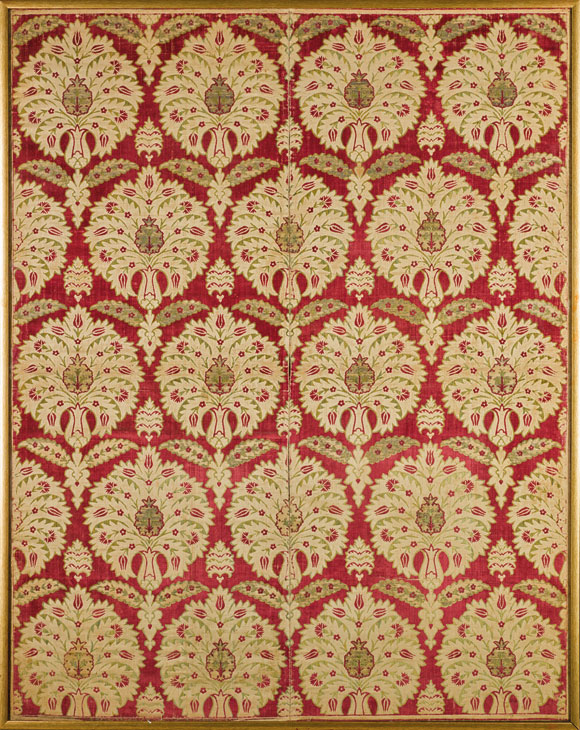

Çatma (late 16th century), Bursa or Istanbul. Sotheby’s London (£80,000–£120,000). Image courtesy Sotheby’s

Not all works are modern or contemporary either. October also sees Islamic Week in the London salerooms and galleries. Textiles steal the show at Sotheby’s. From the collection of the decorator Serge Brunst comes a large, late 16th-century Ottoman voided silk velvet and metal-thread çatma panel ornamented with carnations (£80,000–£120,000celebr). Testimony to the Indian passion for pearls is a magnificent coat probably made for a young prince, its gilt-metal appliqué work and embroidered flower-form panels filled with fine Basra seed pearls (£150,000–£250,000).

PAD London – once known as the Pavilion of Art and Design and as a civilised antidote to the user-unfriendliness of Frieze – returns increasingly to its design roots, not least after the defection of some exhibitors to Frieze Masters. Not only 20th-century and contemporary design but also jewellery, antiquities and tribal art are firmly in the frame with the Frieze crowd. Not to be overlooked are those works which fall at the intersections of art and design, craft and sculpture, such as the extraordinary wood pieces by Ernst Gamperl (Sarah Myerscough Gallery; £5,000–£20,000); and the forged and cast steel or silver of Junko Mori (Adrian Sassoon, £4,500–£44,000).

From the October 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.