This weekend I took receipt of a new bookshelf, which I’d swapped with a friend in exchange for a ratty old sofa for which I had neither space nor use. This in itself is an innocuous statement: but really, you should have seen my bedroom. It had become utterly impassable. Ziggurats of books blocked all paths, the floor was carpeted in old press releases and towers of exhibition catalogues (c. 2005–16) made getting into bed an Olympic sport.

The piles of art writing had ceased to give me any pleasure whatsoever. Art had not only taken over my life, it was actively obstructing it.

Bookshelf installed, I began to sort through the ruins of my library. Aside from other people’s writing, there was a complete record of my own, vaingloriously preserved, efforts. One of the first things I came across was my first published article – a review of a Damien Hirst show at the Serpentine in 2006. I quite liked it, it seems. Plus ca change.

*

Next up was a catalogue for a brilliant Robyn Denny show put on by the Laurent Delaye gallery in 2013. Since then, Delaye has given up his Savile Row space in favour of mounting site-specific shows. It’s a bold move for a commercial gallery, but so far it’s paid off handsomely. The latest one – at the Embassy of Brazil just off Trafalgar Square – opened last Thursday, and I can’t recommend it enough.

The show is devoted to a series by photographer Jason Oddy, who travelled to Algeria in 2013 to document the monumental university campuses Oscar Niemeyer built in Algiers and Constantine between 1968 and 1975. Though largely forgotten now, these masterpieces – which the architect behind Brasilia counted among his favourite projects – are still in use, albeit in urgent need of renovation.

The Rectorate II, Houari Boumediene University of Science and Technology, Bab Ezzouar, Algiers, Algeria (2013), Jason Oddy.

The government in Algiers had asked Niemeyer to submit plans for various public projects that it hoped would show off a new, progressive image for Algeria after almost a century and a half of French colonial domination. Arguably, Algeria was even worse off than many other African countries post-Independence. The French had not only conquered and divided it, but since 1870 had propagated the myth that this vast nation was actually an integral part of France. In the 1950s a bloody guerrilla war had broken out, but it was only in 1962 that Algeria was granted its freedom. No wonder the government was keen to establish a new national identity. Niemeyer took to the project enthusiastically, though sadly many of the designs he made – including a mosque with an inverted dome – remain unrealised.

Oddy’s photographs of the two university complexes are like snapshots of a fallen civilisation. Beautiful curved concrete is all but abandoned to nature, and you can almost hear the echoes of the wind resounding through the deserted lecture halls. On the rare occasion that you can distinguish figures in these pictures, they are fleeting, ghosts of an altogether more optimistic past: namely, the era prior to the outbreak of Algeria’s apocalyptic civil war in 1991. This is a show that has it all, and sends a shiver up the spine even on the warmest spring evening.

Bloc des Salles de Classes IV, Houari Boumediene University of Science and Technology, Bab Ezzouar, Algiers, Algeria (2013), Jason Oddy

*

Next in my clear-out came a stack of Lisson Gallery literature. I’ve seen some highs and lows there, but on balance, it’s always been my favourite of London’s blue chip galleries. In part, this comes down to location: there are two first rate second-hand bookshops within five minutes’ walk, and I once saw a man walk a goose up Bell Street on a leash. Beat that, Gagosian. Anyway, now is a good time to visit.

‘John Latham: Spray Paintings’, installation view at the Lisson Gallery.

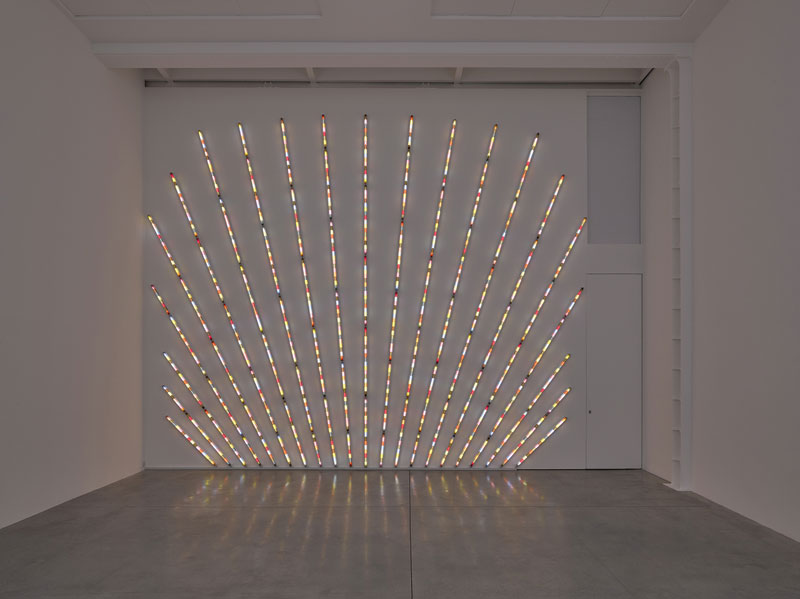

The Lisson’s John Latham exhibition is a treat. I can’t think of any show I’ve seen in the past five years that better evokes just how radical and exciting a period the 1960s were for British art – it’s certainly better than the Tate’s survey of British conceptual art, at any rate. Spencer Finch’s show at Lisson’s second gallery is also great fun. Optical trickery aside, who could resist the opportunity to see Martian colour recreated within a white cube? Not me.

Spencer Finch, ‘The Opposite of Blindness’, installation view at Lisson Gallery. © Spencer Finch. Courtesy Lisson Gallery. Photography: Jack Hems

*

Back to the books. I was on the brink of giving up when I dug out a London property guide published in 1971. This really was an object to make the mind boggle: Islington, for example, is described as an area ‘easily seized on by a pioneering core of young artists.’ This is a statement to which the reader of 2016 can respond with nothing but a grimace. My own suburb is summed up as ‘beginning to look interesting.’ Forty-five years on, I can assure you that the authors were delusional.

In a roundabout way, my point is that by the time the next London Diary appears, the city will have gone to the polls to decide its new mayor. Whoever it chooses will have to make some incredibly bold decisions if they are to correct the faults of their two predecessors – and I strongly suspect that they won’t. Perhaps it’s just the effect of the latest addition to my library (Rowan Moore’s Slow Burn City) but I’m pessimistic as to how far any incumbent of the mayoral office can distance himself from the rapacious march of property development.

Since the office was established in 2000, London has physically changed almost beyond recognition – in no small part due to new powers granted to the mayoralty in 2008, which allowed the incumbent to call in and overturn local council decisions on planning applications of strategic importance. In my view, we have lost too much to an unsympathetic construction boom. If this – and the price rises and social exclusion that logically follow – are the price of progress, perhaps it’s time for a period of stagnation.