Last November this publication carried an interview with Kjeld von Folsach, director of the David Collection in Copenhagen, a private museum which in recent decades has specialised in collecting and exhibiting Islamic works of art. Despite current global tensions, von Folsach argued against self-censorship, remarking ‘we cannot allow our displays to be influenced by contemporary attitudes’. Presumably this way of thinking is shared by the Smithsonian in Washington, which has mounted a collection of more than 60 historic Qur’ans at its Sackler Gallery (‘The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts’, until 20 February). Given that news from the region in which the majority of these objects were produced repeatedly carries reports of artworks being destroyed, the exhibition offers a timely alternative perspective on the Middle East as a centre of cultural inventiveness.

Writing in the July 1981 edition of Apollo, Mahonri Sharp Young likewise enthused about the degree of creativity demonstrated over the centuries by members of the Muslim faith. Young had been to see ‘Renaissance of Islam: Art of the Mamluks’ then running at the Sackler’s sister institution in Washington, the Freer Gallery, and was clearly dazzled by the richness and complexity of the items on display.

His fascination was all the greater because of the circumstances under which the work had been produced. Predominantly of Turkic origin, the Mamluks were a caste of military slaves who from the mid 13th to early 16th century ruled over an empire that controlled Egypt, the Levant and what is now western Saudi Arabia: their first sultans were responsible for recapturing all territory in the area held by Christian crusaders.

The martial nature of Mamluk society might lead to a supposition that its members preferred wreaking havoc to engaging with creativity, especially since the regime was regularly punctuated by coup plots, uprisings and purges, as well as wars against neighbouring states. However, Young cited the 1981 exhibition’s curator, Dr Esin Atil, who commented: ‘The age of the Mamluks was the Renaissance of Islam and the culmination of its artistic genius.’

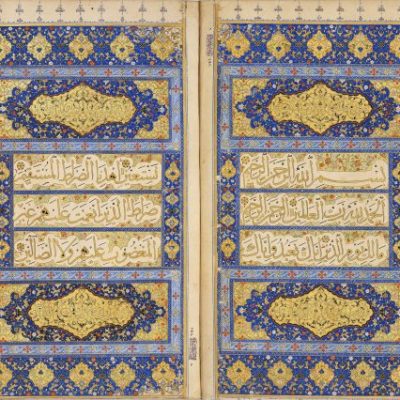

Single-volume Qur’an (1340–41), copied by Arghun al-Kamili, possibly Iraq, Jalayirid period. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul

Young could not fail to agree, observing that the majority of the exhibits had originally been made for public buildings, in particular religious complexes. Among them were elaborate metalwork candle stands and glass lamp holders, always inscribed with the same verse from the Qur’an: ‘God is the light of the heavens and earth, a likeness of his light is like a niche in which there is a lamp.’ The impact of their craftsmanship was widespread, with orders for goods made in Mamluk workshops coming from Western Europe. Specifically, wrote Young, ‘The influence of Mamluk metalwork was strong in Venice, which was in many respects an artistic outpost of Islam.’ Furthermore, ‘Venetian glass stemmed from the Islamic tradition, and it survived in Italy long after its manufacture had dwindled in Egypt and Syria…’

Perhaps the greatest effort and skill was reserved for the production of sacred texts. ‘The Mamluks,’ Young explained, ‘with the zeal of converts, donated a set of Qur’ans to each of the great religious foundations which were the characteristic institutions of their reign.’ Their speciality was the 30-volume Qur’an (corresponding to the number of days during the sacred month of Ramadan), as well as single volumes more than a metre high. Again he quoted Dr Atil’s declaration, ‘…the exquisite illumination calligraphy and bindings of Mamluk Qur’ans are unequalled in any other Islamic tradition of bookmaking’. As members of the Sunni denomination, Mamluks prohibited the depiction of sentient beings, thereby encouraging the development of calligraphy and abstract ornamentation for their religious texts, as can be seen in the current Sackler exhibition.

That so many ancient Qur’ans have survived when much else has perished is no coincidence. In the first place, every text incorporating words from the Qur’an is regarded as sacred and worthy of preservation. More practically both in Egypt and Turkey, from where most of the volumes now on show in the Sackler have come, government authorities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries scrupulously gathered up ancient manuscripts from mosques and other religious centres for safekeeping, thereby ensuring their future.

No culture or religion has a monopoly on creativity, or on spoliation, as a visit to some of England’s great medieval monasteries will testify. Young’s engagement with Islamic art in 1981 reminds us that as much as any other, the Muslim religion has enhanced our world.

From the February 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.