From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1923, at the start of their collaboration on what would become The Adventures of Prince Achmed, Walter Ruttmann asked Lotte Reiniger, the film’s creator, director and chief animator, why she was making a fairy tale – what did it have to do with the year 1923? ‘Nothing at all,’ she told him. ‘And why should it? I’m here, living in the year 1923, and I have the chance to make this film, so naturally I’m going to do it. That’s all it has to do with the year 1923.’

The exchange encapsulates the paradoxical nature of Reiniger’s films. She was a pioneer, inventing both the aesthetics and the techniques of a new art form, the silhouette film, in which figures cut from card or thin lead moved across often gorgeous backgrounds, story and emotion conveyed not through words or facial expression but through gesture and exquisitely observed details of outline (many of the figures and backgrounds themselves are today held in the Stadtmuseum Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg). According to her friend Hans Richter, an artist and experimental film-maker associated with Dadaism, she ‘belonged to the avant-garde as far as independent production and courage were concerned’; and in the Berlin of the 1920s and ’30s, she had friends and colleagues among the avant-garde, working at the experimental film house the Institut für Kulturforschung (Institute for Cultural Research) and counting Bertolt Brecht and Lotte Lenya among her friends. But she showed none of the desire to capture the zeitgeist, search for meaning, propagate a political message or start an artistic movement that you expect to find in the avant-gardiste. It’s not quite true that, as Richter claimed, the spirit of her work was Victorian – it’s more unbuttoned and subversive than that; but it does look back, to classical ballet, commedia dell’arte and, throughout her life, fairy tales. Watching her romantic, ethereal animations, I’m reminded of the critic James Wood’s observation on P.G. Wodehouse: ‘His innocence is rare; but even rarer is the combination in his books of muscleless play and serious, intensely controlled literary talent.’

Background designed by Lotte Reiniger for The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Stadtmuseum Tübingen

She is known now mainly for Prince Achmed, though for decades it was unseen and all but forgotten. Its claim on our attention rests partly on its primacy: released in 1926, it is the oldest surviving animated feature (Quirino Cristiani in Argentina made two earlier films that are lost) – Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs didn’t come out until 1937. But it is also simply a remarkable film. The story is an orientalist concoction of ingredients from the Thousand and One Nights, in which Achmed, son of the caliph, is carried away on a flying horse conjured up by a wicked sorcerer, to land in the magical island of WakWak, where he falls in love with a princess disguised as a bird, battles a giant serpent and demons, and is helped by Aladdin – whose own story is told in flashback – and the sorcerer’s enemy, the witch of the burning mountain. In the end, evil is defeated, Achmed marries his princess, and Aladdin marries Achmed’s sister. The magic of the story lies less in the somewhat silly plot than in the visuals. The backgrounds are a monochrome fantasy (though not black and white: the modern restoration of the film, available on a disc issued by the British Film Institute, restores the original tints, deep blues and warm yellows): palaces with elaborate Islamic filigrees and ogee curves, forests of tropical ferns – it’s hard to grasp how such minute detail could be produced by one woman working with her scissors. The same fineness of line is seen in the sharply delineated characters: the wicked magician with his spiky nose, chin and elbows, his talon-like fingers and malevolent, rolling eye; the rounded, earthy savagery of his witch opponent; the slender beauty of the princesses – and the feathery costumes of Achmed’s beloved and her maidens in their bird guise – and the youthful smoothness of the heroes. Several sequences in the film have an ecstatic beauty, some of it due to the experimental techniques of her collaborators, Ruttmann and Berthold Bartosch: the sorcerer dancing and gesticulating around amorphous swirls of black that become the magical horse; the caliph’s birthday, the screen alive with tiny figures, warriors and acrobats, the caliph himself carried in a richly ornamented litter slung between two elephants; Achmed’s uncontrolled flight through a storm and across a starry night sky; the bird princess and her maidens landing to bathe in a pool by night; the battle of the sorcerer and the witch, in which they shapeshift into lion, scorpion, snake, eagle; Aladdin’s summoning of a giant, blurry genie…

Still from ‘Harlequin’, directed by Lotte Reiniger and originally released in 1931. Munich Stadtmuseum. Photo: INTERFOTO/Alamy Stock Photo

Reiniger was only 26 when Achmed was released – to applause and some commercial success, particularly in France. She carried on producing films almost to the end of her life – around 60 of them, two thirds of which survive; nothing else she produced matches it, in scale or sheer beauty, and she was never again such an innovator, though her films became more technically accomplished, her characters moving with more grace and precision. While her films only fleetingly had mass appeal, they can still delight and enchant: my personal favourites would include the poignant erotic comedy of Harlequin (1931); the feminism-tinged take on the Pygmalion story in Galatea: the Living Statue (1935); Thumbelina, one of a number of short fairy tales she made for television in the 1950s, with its cast of grotesque frogs and refined butterflies and fairies; and her marvellously coloured Christmas story The Star of Bethlehem (1956), in which decidedly non-canonical hordes of devils erupt out of an abyss to harass the Magi on their journey.

Silhouette art existed long before Reiniger: a number of Asian countries have their own longstanding shadowpuppet traditions, such as the wayang theatre of Java, in which figures of wood or leather are manipulated with rods behind a thin fabric screen, backlit. In Europe, shadow puppets became popular in the 18th century – the galanty show in Britain, the ombres chinoises in France; shadow plays were still a popular feature of the cabaret at Le Chat Noir in Paris in the 1890s. Reiniger took an interest in these older forms, visiting Greece to see the satirical Karagiozis shadow theatre in the 1930s, and publishing a book, Shadow Puppets, Shadow Theatres and Shadow Films, when she was in her seventies; it is not clear that she knew anything of these traditions when she started to make her own shadow plays, as a child. The art of cutting silhouette portraits had become popular in Europe in the late 18th century, in part influenced by the physiognomist Lavater, who insisted that the outline of the face was the most reliable indicator of character. Hans Christian Andersen, whose fairy tales provided the basis for a number of Reiniger’s films, was famous for his dexterity as a silhouette artist. Reiniger was, by her own account, gifted in several artistic directions, but it was her brilliance at cutting silhouettes that stood out: many people commented on the speed and virtuosity with which she snipped out the most elaborate figures. For her films, she cut out the different parts of a figure to be articulated and joined them with wire, hammering the joints flat; leading characters would require several figures at different sizes, to create long shots and close-ups. Heads and legs were always in profile, bodies seen front on, like ancient Egyptian drawings; but there is rarely any sense of strain or artificiality as they move. She studied motion closely, visiting the zoo to get a sense of how animals moved and getting down on all fours to imitate them, insisting that the animator had to feel their movements from the inside. For filming, the figures were laid out on what she called her Tricktisch, or trick table, which had a glass screen cut into the middle of it, a rack containing layers of scenery painted on glass to create an illusion of depth (Disney seems to have copied this notion), a light source below and a camera and secondary light source poised above. The processes of stop-motion animation were already well established: photograph the scene, move the figures infinitesimally, photograph; but Reiniger’s ability to see the entire scene, to produce multiple competing movements, is stunning – look at the parade of soldiers and the juggling acrobats at the start of Prince Achmed. Silhouette films turned out to be an artistic cul-de-sac; but how they pulse with life and wonder.

Lotte Reiniger (1899–1981) at work in 1934, Paul Mai. Photo: Paul Mai/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Reiniger was born in Charlottenburg, Berlin, in 1899. In her teens, she trained as an actress, playing spear-carrier roles in the theatre and selling silhouette portraits of the actors to make a little money. The actor-director Paul Wegener – something of a hero to the young Reiniger – employed her to make silhouette titles for the film Rübezahl’s Wedding (1916), which he co-directed with Rochus Gliese. When real rats turned out too unpredictable to work with for Wegener’s 1918 version of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, Reiniger made animated wooden ones to swarm after the piper. Through this connection she met Hans Cürlis and Carl Koch, who invited her to join the newly founded Institute for Cultural Research; and out of this came her animated short The Ornament of the Loving Heart in late 1919. Out of it, too, came marriage to Koch, who until his death in 1963 was her main collaborator. She proceeded to make an animated advert, The Secret of the Marquise, featuring figures with Marie-Antoinette hair and dresses who owe their beauty to Nivea cream. More short films followed, including the amusing, Andersen-inspired The Flying Coffer and a notably savage Aschenputtel (Cinderella), in which an ugly sister slices off great chunks of her foot to squeeze into the slipper. Work on an animated sequence for Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924) came to nothing; but Louis Hagen, a banker who had sunk some of his money into reels of film stock, offered to back a full-length feature, giving her both the film and a small house to work in. The result, Prince Achmed, took her and a staff of five (including her husband, Ruttmann and Bartosch and the composer Wolfgang Zeller) three years to make.

More success followed. Though a feature based on Hugh Lofting’s Dr Dolittle stories was unfinished, enough was completed to offer three episodes, which became a popular hit in Germany: watched now, they seem crude after Prince Achmed, and entertainment value is severely diminished by the caricatured African characters. She and Koch worked with Gliese on a live-action film about a troupe of shadow-puppeteers, The Pursuit of Happiness (1930), with a cast that included the great French director Jean Renoir (a friend since the Paris premiere of Prince Achmed) and Bartosch; but after a late attempt to convert it from silent to sound film, the result – long lost – was reportedly a mess.

Papageno and Papageno (1971), Lotte Reiniger. Stadtmuseum Tübingen. © DACS 2021

With the rise of Hitler, Reiniger and Koch tried to leave Germany and, unable to get permanent residence elsewhere, spent much of the 1930s wandering Europe, together and separately. Reiniger spent time in London, making films for the GPO Film Unit – The Tocher (1938), a charming Highland fantasy-cum-fairy ballet with a score adapted from Rossini by Benjamin Britten, and The HPO (1938 – it stands for ‘Heavenly Post Office’). This last is interesting as an early experiment in colour, featuring a cast of cherubs made of white outlines on a background of blue sky rather than the customary silhouettes; it has a score by Brian Easdale, who went on to work with Michael Powell on films such as The Red Shoes (1948) that sometimes seem close in sensibility to Reiniger. Koch, meanwhile, became Renoir’s assistant and co-writer, working closely with him on masterpieces such as as La Grande Illusion (1937) and La Règle du jeu (1939), as well as his patriotic revolutionary epic La Marseillaise (1938), for which Reiniger produced a brief satirical shadow-play. Reiniger and Koch were together in Italy when the Second World War began, working on Renoir’s projected film of Tosca, which in the end Koch directed. They stayed for a while with another of Renoir’s assistants, Luchino Visconti, but in 1943, after the Allied invasion and German occupation, returned to Berlin to care for Reiniger’s mother.

In the late 1940s they moved to north London, taking British citizenship, and Reiniger began a productive, if perhaps less creative, phase – remaking a number of her earlier films in versions aimed more clearly at children: her Cinderella of 1954 leaves out the foot-slicing. She stopped work almost entirely for some years after Koch’s death; but in the 1970s she was to some extent rediscovered, appearing at film festivals and making several more short films – notably a ravishing-looking version of the medieval French romance Aucassin and Nicolette (1975), commissioned by Canada’s National Film Board. She moved back to Germany, dying there 40 years ago, in 1981.

Since then, her reputation has grown steadily, aided by rediscoveries and restorations of her early work – many of the negatives were destroyed in Berlin at the end of the war, and the prints that survived were of variable quality; but clear, sharp versions of many works can be found on discs issued by the BFI and on YouTube and Vimeo. She has been adopted at times as an emblem of marginalised women film-makers, passed over by the patriarchy. There is certainly some truth in that picture: in his ‘psychological history of German film’, From Caligari to Hitler (1947), the cultural theorist Siegfried Kracauer patronised her brutally – her films were ‘just the right thing for small town people and salesgirls with warm hearts and nothing else. In a tiny realm of her own, Reiniger swung her scissors diligently, preparing one sweet silhouette film after another.’ For a start, this overlooks the subversive streak in Reiniger’s early work: in The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) – in which a series of Chinese citizens desperately try to avoid being caught with the apparent corpse of the Emperor’s favourite, Ping Pong – the relationship between Ping Pong and Emperor has an undeniably homoerotic tinge. In Galatea: The Living Statue, after Pygmalion’s statue is brought to life she refuses to submit to his embraces, instead strolling naked through the city to a taverna, where she gets riotously drunk and dances on the table. Reiniger’s take on Carmen eschews a tragic ending for the heroine: instead, she jumps into the bullring, where she wins over the bull, dancing with him and then, triumphantly, on his back. Still, it is true that on the whole she did not repurpose fairy tales à la Angela Carter, instead sticking to traditional narratives ending in marriage.

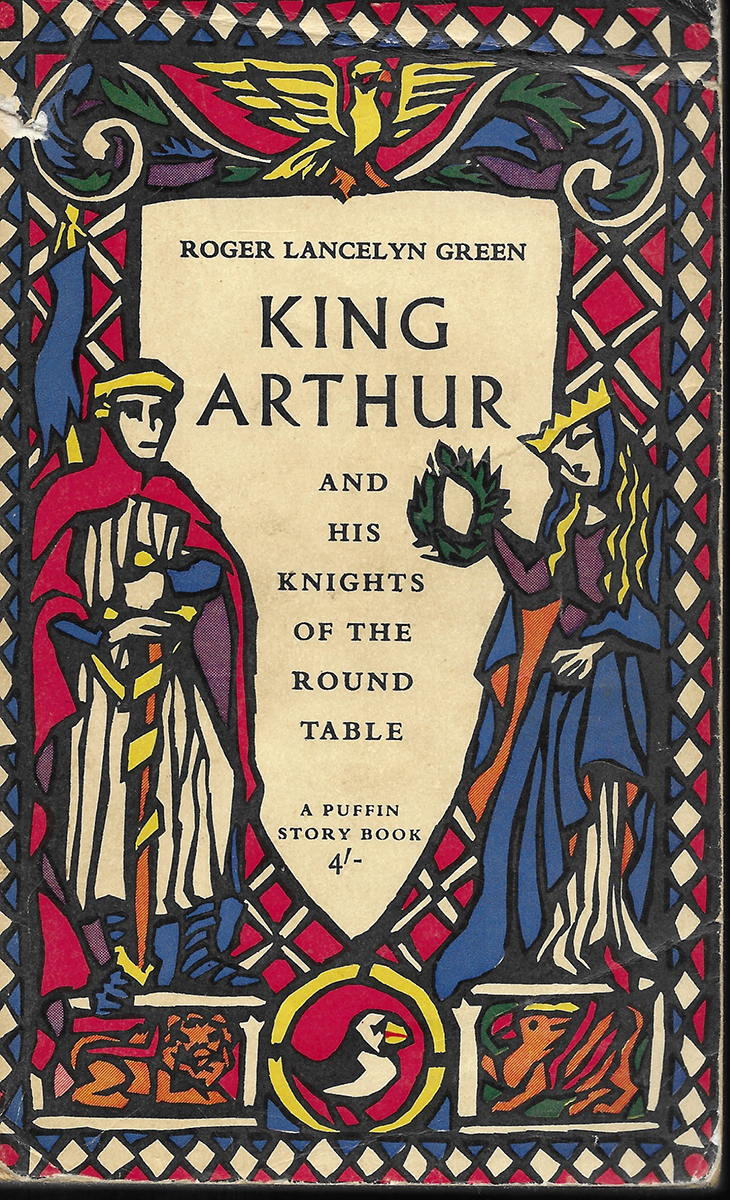

Lotte Reiniger’s cover design for Roger Lancelyn Green’s King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, first published by Puffin Books in 1953

But patriarchy isn’t necessary to explain Reiniger’s marginalisation: in sticking so firmly to silhouette art, in a world where Disney, with its colour and liveliness, had taken hold, she seems to have chosen to remain in a tiny realm. She restricted herself largely to pure black-and-white, too, though she left enough work – including the stunning stained-glass-style cover for Roger Lancelyn Green’s King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table (1953) – to show that she had a marvellous eye for colour.

It is possible, in any case, to overstate how far Reiniger was on the margin of things. You can see in the transformations of Prince Achmed the influence of Georges Méliès, the pioneer of cinema trickery; and her art of shadows has some kinship to the German Expressionist film-makers of the 1920s, Wegener among them. Renoir described her work as the ‘visual expression of Mozart’s music’. Music, usually classical, was central to her art: she would animate to match the music she had chosen as the score, often Mozart, and produced several opera-based shorts, notably Papageno (1935), which plucks the bird-catcher and his beloved out of The Magic Flute. But perhaps what Renoir meant was that like Mozart she created elegant beauty that can at first glance seem tame, but on closer examination reveals darker undertones. She sits comfortably alongside the musical neoclassicists – Stravinsky’s ballet Pulcinella premiered in 1920. Echoes turn up in surprising places: the shadowy figure on the horizon pursuing the children through a starry night down the Ohio river in Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) resonates with Prince Achmed – and Laughton worked with Jean Renoir. A whole British school of jerkily imperfect 2D stop-motion animation for children in the 1960s and ’70s – Noggin the Nog, Ivor the Engine, even Crystal Tipps and Alistair – surely owes something to her. More recently, there have been conscious homages by the French animator Michel Ocelot in films such as Princes et princesses (2000); in Lee Lennox’s wonderful end titles for the big-screen version of A Series of Unfortunate Events, in which the wicked Count Olaf is a ringer for the sorcerer of Prince Achmed; and in the ‘Tale of the Three Brothers’ in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 (2010). Maybe, too, the shadow processions in William Kentridge’s installation art bear her stamp. Her films are presented at festivals and art museums, and have inspired new scores by dozens of musicians – Prince Achmed has been accompanied by the American band Morricone Youth, the British band Little Sparta, and Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble, among others. Lotte Reiniger won’t stay in the shadows.

Still from ‘The Adventures of Prince Achmed’, directed by Lotte Reiniger and originally released in 1926 (duration: 65 minutes); shown here is a modern reconstruction with restored tints, based on a nitrate copy held by the British Film Institute, London. Image courtesy the Stadtmuseum Tübingen

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.