From the January 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I first saw Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s work in early 2012 at the New Museum in New York. I remember, looking at a smallish, square oil painting, the darkness of the paint and the gleam of a grin. The brushstrokes were rough but elegant; they reminded me of Manet, except that there was something forced about the grin that struck me as strange. The exhibition was called ‘The Ungovernables’. There had been riots in London the previous summer and it seemed to me that these dark paintings contained a political message. In the past decade, looking at Yiadom-Boakye’s work I have come to think of it differently.

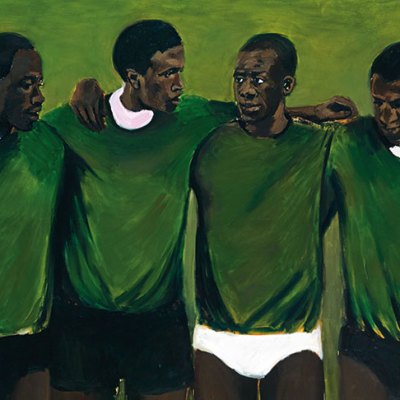

This is particularly true of Man Science, which was created for her solo exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery in London in 2012, the year before she won the Turner Prize. It’s a large-format work – the kind of size that we might be more used to seeing reserved for history paintings – but its subject is three young boys in the shallows of a body of water. There is something provisional about it and the figures could be three studies of a single boy. Yiadom-Boakye paints people who don’t exist, or who exist as figments of her own imagination. This painting, in turn, represents three boys involved in imaginative play: one runs his hands in the water; another skulks in the foreground; the last holds his arms back, as if becoming a bird.

The more time I spent thinking about her work, the less confident I felt that I understood it. Her 2014 exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York was accompanied by a poem that referred to ‘What the Owl Knows’. I began to see the wisdom of protecting the privacy of her own imagination, of acknowledging that being content with ambiguity in art is part of the viewer’s job. Mystery is everywhere in Yiadom-Boakye’s work and we should meet her respect for it with our own.

Man Science (2012), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Photo: Marcus Leith; courtesy the artust/Corvi-Mora, London/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © the artist

These days, what I notice in her work is more formal: the red robe of one sitter that looks like the red of a cardinal in a painting by Velázquez; her interest in necks, and ruffs and necklaces that cut across them; the presence of certain animals as ornaments; more than anything, the relaxed elegance of her young men. Her backgrounds are often dark, rendering her figures outside of time and place. The diffuse brown background in Man Science reminds me of the idiom ‘in a brown study’, meaning a state of deep thought. That’s what we are seeing: three children consumed by their own inner lives. There is something brooding about it but we don’t know what is about to happen. The flatness of the represented space makes the scene vertiginous, as if the water could break down over us.

I now think of Yiadom-Boakye’s titles as short poems, red herrings or Rorschach tests. ‘Man Science’ sounds to my ears like a critique of Enlightenment science and all its mistaken ideas about race. But who knows? Maybe it’s about learning how to swim. The painting always makes me think of the heaving Atlantic Ocean in the film Moonlight (2016), where a father teaches his son to swim. And William Wordsworth’s couplet: ‘see the children sport upon the shore, / And hear the mighty waters rolling evermore.’ If we resist the wish to explain, all our associations become private ways of making sense of the pleasure that the work gives – and we can see these children for the mysteries that they are.

From the January 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.