From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It’s 8.30 in the morning in the Valley of the Kings and, along with the temperature, anticipation is rising among our small group of journalists. We are at the entrance to one of the 62 confirmed royal tombs in these arid hills on the west side of the Nile, the necropolis of ancient Thebes. Since the 19th century the tombs have been numbered in order of their (re)discovery – ‘KV62’, the burial place of Tutankhamun, being the last to be uncovered, in 1922. This one, ‘KV57’, unearthed in 1908 by Edward Ayrton, was made for the pharaoh Horemheb (reigned c. 1319–1292 BC), who had been the boy king’s general. Only a handful of these tombs are open to the public at any one time; Horemheb’s has long been closed for restoration and conservation after flood damage, but we have been granted special access. A key is produced, padlock and chain are negotiated; the door is opened, a switch flicked in a fuse box, and a long descent illuminated.

We are here ahead of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition ‘Made in Ancient Egypt’ (3 October–12 April 2026), which focuses on the craftsmen (and occasionally women) responsible for the decorations and objects within these tombs. Two of the museum’s Egyptologists, Neal Spencer and Helen Strudwick (curator of the exhibition), are our guides, and why they particularly want us to see the tomb of Horemheb becomes clear once we reach the pharaoh’s burial chamber. First, though, like Hollywood-style archaeologists, we must confront some ancient tomb-raider deterrents. ‘Although we think of Tutankhamun’s tomb as an “intact” burial,’ Spencer explains, ‘it was actually robbed three times pretty soon after the burial took place, and then tidied up and resealed. Theft was rampant.’ The tomb of Horemheb, who ascended the throne only a few years after King Tut’s death, attempted to avoid that. After a vertiginous descent, long enough to contemplate what an extraordinary feat of engineering this was, we arrive at a chamber whose floor drops away suddenly – a surprise for any would-be robbers.

Happily there is a modern bridge to carry us safely across this well shaft and from which we can admire the decorations around the chamber: on the ceiling, yellow stars against a blue-grey ground, which continues down the walls, where the king, identifiable by his striped nemes headdress with rearing cobra, is shown making offerings to various deities associated with the underworld: Osiris, Horus, Isis, Anubis, Hathor. These figures, and accompanying hieroglyphs, have been carved in bas-relief and then painted – a new departure at this point in royal tomb decoration, where previously scenes had only been painted.

We walk through a door that had originally been bricked up, plastered over and painted – the intention being to make it seem like the end of the tomb (a decoy that failed even in antiquity). Descending further down, we finally reach the burial chamber. This might feel like an anticlimax if you’re a tourist looking for eye-catching Instagram material, for there is almost no colour here – but for scholars this is a gift of a room: the decoration is unfinished, the intended schemes sketched in black and red, with occasional sections starting to be carved out. (The mummification process for a pharaoh took 70 days; if the tomb was not completed by the time the sarcophagus was in place, too bad – it had to be sealed.) ‘What we can see,’ Strudwick explains, ‘is that an outline draughtsman would come in, probably working from an ostracon [a fragment of inscribed limestone or pottery] which would tell him what was meant to be here, and he would do the red lines, and then either the same artist or a different one would come in and overlay the black lines, and it’s the black lines that are then cut into the surface.’

Among the sketched figures is the ram-headed nocturnal form of the sun god Ra, travelling in his solar boat through the underworld until his ‘rebirth’ at dawn. The coils of a serpent form a protective shield around him as he travels. Snakes, in fact, are everywhere – forming horizontal and vertical borders, spitting fire, or lined up as repeated hooded cobras. These and other scenes are episodes from the funerary text known as the Book of Gates, which sets out the passage of a newly deceased soul with the sun god through the underworld towards resurrection. Knowledge of the necessary ‘spells’ at each of the 12 guarded ‘gates’ was ‘essentially a passport to the afterlife’, as Spencer puts it, and Horemheb’s is the first tomb to illustrate them. The fact that the artists involved in carving and painting these scenes by necessity had access to that knowledge gave them an unusual level of privilege (and literacy) – even if they never employed the Book of Gates in the decoration of their own tombs. ‘These texts are highly restricted,’ Spencer says, ‘and, until the end of the New Kingdom when you start having papyri with them, they’re not shown anywhere except Valley of the Kings tombs – even the queens of Egypt didn’t have this text in their tombs.’

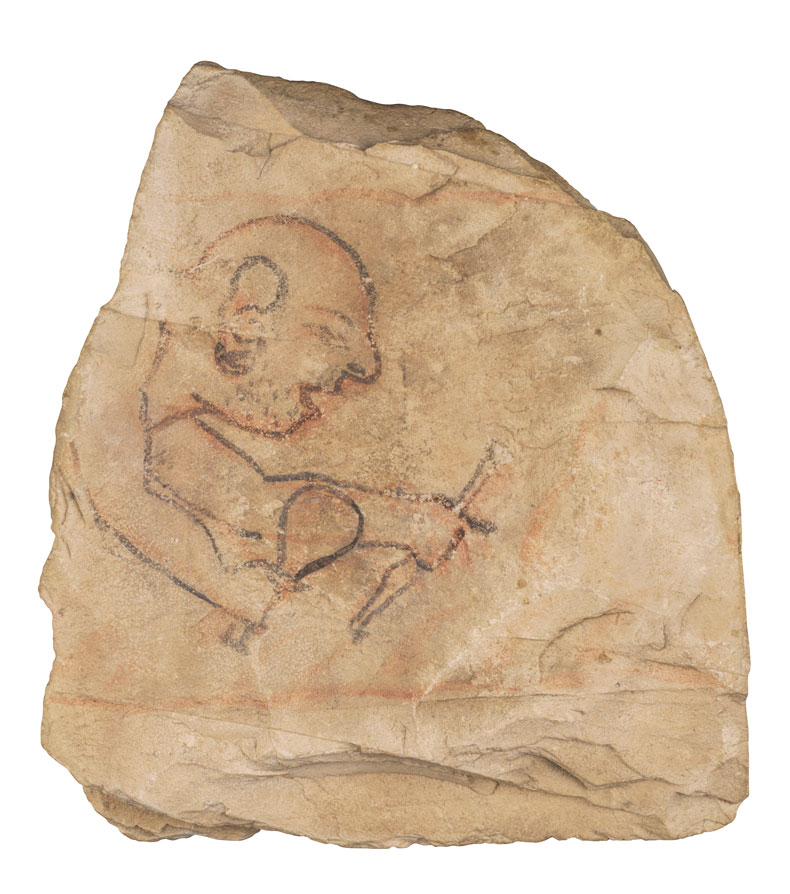

As we emerge from this underworld, squinting through the sun god’s fierce glare, talk turns to working conditions while these tombs were being made. ‘They did four hours in the morning, and four in the afternoon with a break in between,’ Strudwick says. ‘There’s a sketch [on a limestone ostracon, in the exhibition] of a man with a mallet and chisel, and I always imagine someone sitting in a bit of shade on a break, sketching a fellow craftsman. For me this is the place where we meet these people – while we’re here and struggling with the heat ourselves. It was challenging work.’ (Strudwick knows something about operating in high temperatures, having worked on and off on Theban excavations since coming here as a student in the 1970s. On the road to the Valley of the Kings from our hotel we pass Howard Carter’s old house, where, she says, ‘we used to go and play table tennis with the [antiquities] inspectors who were staying there’.)

At the end of a day’s toil in the Valley of the Kings these workers would walk south over the hill back to Deir el-Medina, a walled settlement purpose-built by the state for artisans of the royal tombs and their families. It functioned as such for some four centuries, more or less coinciding with the period of the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 BC). The site was mostly excavated by French archaeologists in the early 20th century, which revealed not only 70-odd small houses but many thousands of texts on scraps of limestone – the ancient Egyptian Post-it note. ‘These ostraca record everything,’ Spencer explains, ‘from the sale of a coffin or orders for a window to divorce proceedings and libel cases.’ Some of them document orders of water from the Nile valley – Deir el-Medina’s necessary proximity to the Valley of the Kings makes it, unusually for a settlement, an inconvenient distance from the river. But that drawback has been posterity’s gain: the dryness of this desert environment has ensured this trove of ostraca’s excellent state of preservation. Not far from here we visit the tomb of Rekhmire (c. 1504–1425 BC), vizier under Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II; its lofty walls are busy with painted figures engaged in the kinds of activities he oversaw in life: carpenters, metalworkers, ceramicists, brickmakers, men on scaffolding working on the kind of colossal statue whose remains can be seen at the mortuary temples of Ramesses II or Amenhotep III. This is the Egyptian machine working efficiently. The texts from Deir el-Medina, meanwhile, tell the other side to this story: broken chisels, fights, absences due to an animal bite, or a funeral, or a hangover. Glimpses of humanity here come courtesy of the makers behind the marvels.

‘Made in Ancient Egypt’ is at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until 12 April 2026.

From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.