Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art should send shivers down the spine of every art expert and wealthy art collector. The documentary, directed by Barry Avrich and now available to stream on Netflix, tells the story of ‘the largest art fraud in the history of the US’ – a salutary tale of greed, hubris and the sins of omission as well as commission.

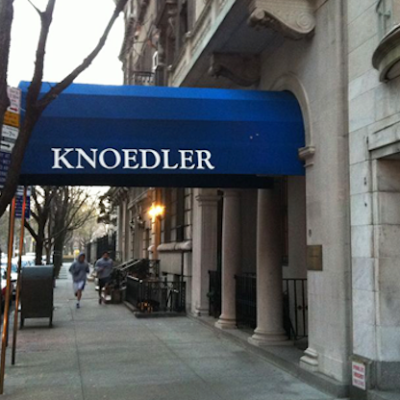

The facts of the case are simple enough. In 1994, a woman from Long Island walked into Knoedler & Co, one of the most prestigious galleries in New York, and offered its president Ann Freedman a painting apparently by Jackson Pollock. The work was previously unknown and undocumented in the literature on the artist. The woman, named Glafira Rosales, was unknown to anyone in the art world, and could provide no provenance or paperwork because her client had apparently sworn her to secrecy. Over the next 14 years, Rosales brought one or two works a year from the same mystery source to Knoedler’s – some 60 in total, all undocumented and purportedly by some of the most sought-after artists on the market: Pollock, but also fellow Abstract Expressionists including Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Richard Diebenkorn. (Rosales also sold works to another New York gallerist, Julian Weissman, who had worked at Knoedler’s in the 1980s.)

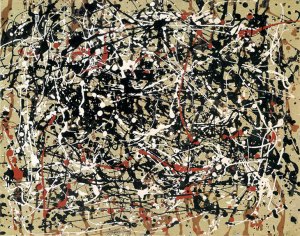

Talking Pollocks – this one’s fake. Courtesy Melbar Entertainment Group

Rosales and even Freedman, it is suggested, were prepared to sell these blue-chip pieces for sums considerably lower than their market value (even so, they were sold to clients for a total of more than $80m). Yet all of these works, it transpired, had been recently produced in a garage in Queens by a Chinese emigré artist, Pei-Shen Qian, apparently recruited by Rosales’s boyfriend, José Carlos Bergantiños Diaz – a man with a criminal history of passing off goods (after his interview for the documentary, he tries to flog to Avrich what he claims is Bob Dylan’s harmonica). Diaz, the authorities believe, was responsible for ‘ageing’ these putative masterpieces from the late 1950s and early ’60s and providing appropriate frames.

The documentary invites us to marvel at the genius of Pei-Shen Qian, who seems to have been able to mimic the work of any artist and produce paintings that viewers found staggeringly beautiful. (Most no longer held the same opinion after they were exposed as worthless fakes.) These paintings, we are told, fooled everyone: dealers, scholars, conservators and even the relatives of the artists themselves. Even if you were familiar with the case, the documentary offers reminders of some quite astounding details. We see a ‘Rothko’, for instance, hanging as the centrepiece of an exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler, and a letter from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., regarding works that the museum apparently intended to include in a catalogue raisonné of Rothko’s works on paper. (Accounts of court proceedings suggest that not all the experts cited believed in – or had even seen in person – the paintings in question, but an essential trope of any art exposé seems to involve experts with proverbial egg on their faces.)

According to Mark? A Rothko or a ‘Rothko’ in ‘Made You Look’. Courtesy Melbar Entertainment Group

The key question here – morally and legally – is whether Ann Freedman and Knoedler believed they were selling authentic works of art or forgeries. Was Freedman a knave or a fool, and which is more forgivable in the contemporary art world? The documentary offers much smug mocking after the event by talking heads who gleefully point out the red flags she should have noticed – and, goodness, there were enough of them to line a Manet Rue Mosnier. Yet Ann Freedman’s testimony, if we believe her, suggests that she was motivated by an all-too-human desire: to make a new discovery and be the one who has brought fresh masterpieces to light. Her failure at first was possibly no more than the suspension of disbelief. More alarming is her dismissal out of hand of the results of scientific investigations initially undertaken at the behest of one of the buyers – and these included anomalies such as pigments that had not been invented at the time the paintings were supposedly created, techniques an artist had not used, and even a spelling mistake on one signature. By this point, Freedman and Knoedler’s were too invested to be able or willing to step back.

Ann Freedman – the former director of Knoedler gallery – in the spotlight. Courtesy Melbar Entertainment Group

What is striking about this documentary is that none of the principal characters – including those who were willing to be interviewed at length by the film-makers – come out very well. The picture painted of the upper echelons of the art trade was far from salubrious. No surprise there perhaps, but it is a sad state of affairs that anyone buying from a reputable art gallery with a more than 150-year-long history should think of having to undertake due diligence. In the end, the lawsuits against Knoedler’s and Freedman were settled out of court and out of the public eye – as befits a type of business that has long been criticised for its lack of transparency. Only Glafira Rosales saw any jail time; both of her alleged co-conspirators fled the US, for Spain and for China, before they could be prosecuted. Few would argue that justice, in the broadest sense, was done.

Any viewers consoling themselves that the refined Old Master paintings they collect are far less easily faked than the scribbles and splotches of Abstract Expressionism should read Vincent Noce’s book L’Affaire Ruffini: Enquête sur le plus grand mystère du monde de l’art, which recently landed on my desk. It tells the story of Lino Frongia, now 62, who is suspected of having forged works that were touted as by artists as stylistically diverse as Lucas Cranach, Frans Hals, Parmigianino and Orazio Gentileschi – and who, it seems, got away with it for years.

Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art (2020; dir. Barry Avrich) is streaming on Netlix.