From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Dagen Efter (The Day After) (2020), Mamma Andersson. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk. Courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirne

Here are some titles of paintings by Mamma Andersson: Dead End, Dog Days, Doldrums, Humdrum Day, Lull, Last Waltz, The Lost Paradise, Dagen Efter (The Day After). If you’d never seen a single work by the artist widely considered to be the pre-eminent Swedish painter of her generation, you might still glean some sense of her work from those titles, though not of her canvases’ alkaline beauty. Andersson, who is in her late fifties and whose work swivels between landscape, intimist still life and a guarded kind of portraiture – and sometimes is all of these at once – is a maker of motionless things that nevertheless, and unmistakably, have time encoded in them.

Take Dog Days (2011), one of 58 works in her current retrospective at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, and characteristically based on a found black-and-white photograph (this one sourced via a police officer in Stockholm, where Andersson lives). It depicts a crime investigation mid-dig, replete with shovels, buckets and hazard tape; three excavators in pistachio-coloured outfits dig through the earth, one covering their face or perhaps shielding their nose from decomposition’s stink. A black blur, an artefact of Andersson reworking her canvas, erasing something, hangs centre stage, ambiguously symbolic. The image pauses us before a dark revelation, holding it perpetually and almost consolingly offstage.

Dog Days (2011), Mamma Andersson. Lena and Per Josefsson Collection. Photo: Per-Erik Adamsson; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

This sense of painting extending its timeframe has been Andersson’s wheelhouse since the early 2000s, when her new survey show begins (itself titled ‘Humdrum Days’, referring back to a 10cc lyric from the 1970s, to the artist’s halcyon youth and, arguably, to the domestic containments of our pandemic present; until 10 October). Even in a domestic interior such as Flunkey (2010), there’s a presiding sense of off-ness and foreboding about the two figurines placed oddly next to a double stainless-steel sink, with pairs of sharp scissors hanging above; while a landscape painting like The Day After (2020) depicts a stretch of lakeshore – in Hälsingland, central Sweden, near where Andersson grew up – glowing an irradiated red. Andersson originally planned to study film-making and, via email, I suggest to her that her paintings often recall the early stages in a horror movie, when everything is relatively pleasant but you know it won’t stay that way.

Flunkey (2010), Mamma Andersson. Lena and Per Josefsson Collection. Photo: Per-Erik Adamsson; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

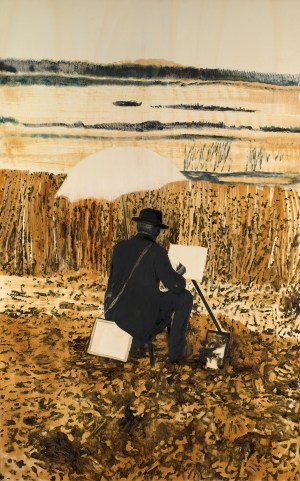

‘That’s very close to what I’m looking for,’ she generously affirms. ‘The Shining, for example, is absolutely the best and most horrific before hell breaks loose. What’s so special about it is that it holds that tension almost 70 per cent of the way through the film – a slow, unpleasant atmosphere.’ This is not to say that all of Andersson’s works hum loudly with alarm, though they regularly attune themselves to the psychological frequencies of place. A pastoral canvas like Star-Gazer (2012), in which an amateur painter, a man in a dark suit, sits in a wheat field shielded by a white umbrella and at work on a white canvas, might on its own appear merely enigmatic and anachronistic (as with most of Andersson’s paintings, the technological trappings of the modern world do not appear). But her practice is contextual, in terms of meaning-making, and more explicit tensions in other canvases can infect outwardly bucolic works. It’s perhaps not irrelevant, for example, that this is a painting of nature; that the central character needs shelter from potentially inclement weather; and that his canvas – the image of the landscape to come – is a blank, a void. But you might need other, heavier canvases in proximity for those aspects to make themselves felt.

‘On the surface, everything appears to rest quite calmly,’ says Andersson when nudged about the potential ecological dimensions of her art, ‘but visual signs increasingly show that we’re on our way to something not so wonderful. Ice caps melting, forests being devastated, the sea running out of fish, insect species disappearing one by one…’ Again, consider her eschatological titles: the after-the-party scene, a deserted revellers’ table strewn with empty bottles, of Last Waltz (2020) – which Andersson started, basing it on an East European theatre scene, then discarded, then reworked – or the rumpled bedroom, absent of an inhabitant but with an exhausted house plant at its centre, of Tick Tock (2011). And consider the importance, amid this suggestiveness, of leaving space for the viewer’s own agency: ‘A painting,’ Andersson says, ‘is always frozen in its own moment in time, and only the viewer can trigger the imagination of a before and after, [although] certainly the artist can direct them, to a certain extent.’ There is a politics of reception here, and a sense of knowing when to hold back. This is not easily articulable, though. In a statement for an exhibition last year at David Zwirner in New York, Andersson said that ‘this exhibition represents the situation we are currently living in on the planet,’ but went on to say ‘I do not see myself as a political artist […] However, I am both critical and analytical. To me, art is about poetry.’

A line I read on social media somewhere: ‘Did you have a happy childhood or are you funny?’ Similarly, one might think that comfortable childhoods are not fertile grounds for art-making, and one issue Andersson’s art addresses is: what do you do, in terms of material, with that kind of upbringing? For this, by her own account, was her experience, and her art is unabashedly replete with bourgeois signifiers. (Even her chosen forename de plume – which she adopted to distinguish her from a fellow student also called Karin Andersson – feels consciously cosy.) Andersson, though, has found a way to leverage horse rides through the forest, chintzy suburban Swedish interiors, and the bourgeois contours of landscape painting per se: in her art’s ecosystem of counterweighted feeling, they are all imperilled pillars of comfort, in an ambiguous temporality, a little lost. ‘In my paintings, I let go of the exact time, avoiding obvious markers like mobile phones, crinoline etc.,’ she says. ‘I was born in 1962, so the late ’60s and the early ’70s is the period that shaped who I am today; it represents an analogue past on the cusp of our era.’ Is that moment truly gone? The paintings won’t answer.

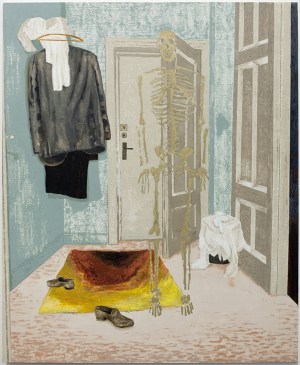

The Long Goodbye (2015), Mamma Andersson. Länsförsäkringar Norrbotten Collection, Luleå. Photo: Per-Erik Adamsson; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

Star-Gazer (2012), Mamma Andersson. Collection of Margot and George Greig Photo: Per-Erik Adamsson; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

Sometimes the work is literally populated by ghosts. In The Long Goodbye (2015), in a small room with a colourful rug on the floor and clothes on hangers, a spectral skeleton hovers, both an omen ghosting the domestic scene and a strayed revenant from one of James Ensor’s danses macabres. The double feeling of such works, of safety and dread, also projects us into the future: it allows for facing up to fears of what’s to come – our own inevitable extinction, say, or a larger one – from a position of relative refuge. It is melancholy, but not necessarily defeated. Or, at least, that’s how it strikes this viewer; but maybe Andersson didn’t pre-plan all that, as to hear her speak of it, she works from a position of instinct, not second-guessing her own psychology too much.

Andersson’s practice begins with photographs, mostly black-and-white, from her book collection – her studio, as seen in a video tour and interview on the Louisiana website, resembles a well-stocked library that also has paint and canvases in it – and she browses images until something in one arrests her, often combining elements of several photographs in one painting. ‘Even if I do start with a colour photograph, I usually make it into a black-and-white image,’ she says. ‘It gives me complete freedom. In terms of colour, I have no strategy, no rules, I just go by pure intuition. You never know what you’ll make – it’s the same as in life, we think we are doing something that will lead to something specific, but then you end up somewhere completely different – and only in retrospect do you understand what it was about and what it led to, in terms of experiencing the meaning of the painting. Sometimes, that takes years.’

This seems appropriate: Andersson’s art has much to do with the value of addressing issues sidelong, not staring them full in the face and certainly not succumbing to monolithic rhetoric. For a long time, notably – after her early career – she avoided painting people whose gazes met ours. The figures in Star-Gazer and Dog Days were characteristic in looking downward or away; Gooseberry (2013) and Underthings (2015) both feature half-undressed young women who seem unaware we’re there; in Holiday (2020) we see a string of horse riders from behind, as if one of the caravan. For Andersson, this is connected to keeping painting’s energy field open and mobile: ‘As soon as a figure has its face turned to you, your gaze stops there,’ she says in a discussion with Marie Laurberg, the curator she collaborated with on ‘Humdrum Days’, in the exhibition catalogue. That leads to a direct transaction with the painting – with one part of it – whereas Andersson prefers, it seems, for something to remain out of reach, so you reach towards it.

Underthings (2015), Mamma Andersson. McEvoy Family Collection. Photo: Mark Blower; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

One way of adding static to the transmission, for her, has been to use dolls as surrogate humans, another signifier of her childhood times, though here they tend to suggest a loss of innocence: Hasch Hisch (2020), an array of broken porcelain faces with gnarly expressions (that do face us), was based on a photograph of figurative pottery that had reputedly been used for smuggling – as the title suggests – hashish, from Turkey or Morocco in, yes, the 1970s. But all of this is also another way of re-enchanting a problematic, seemingly weary pictorial genre, in this case the portrait, and Andersson’s work can be read as a high-wire approach to finding something new in painterly formats that may otherwise feel hackneyed. How do you make a Scandinavian landscape new, relevant to the 21st century? Maybe suggest it’ll soon be burning. How to give life to a timeworn motif like two people in a rowboat on a lake (Doldrums)? Make it explicitly emotional – the water pitch-black and viscous – and nestle it, more largely, within a haunted body of work that suggests risk around every corner, the spectre of rising waters in the future. Of course, as ever in Andersson’s work, the possibility subsists that all of that is just in your mind, mere projection. The work only suggests that we, culturally, are in the doldrums, amid the calm before the storm – not what the storm will be like or even if there’s bound to be one. Andersson doesn’t confront apocalypse directly, but suggests that if you have one foot in the comfortable, the familiar, the antiquated, you’ll be better placed to countenance it.

Hasch Hisch (2020), Mamma Andersson. Photo: Per-Erik Adamsson; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

Some of Andersson’s best work does not put itself in the services of narrative at all, partaking more of sheer, stage-managed enigma. In Hypnos (Hypnosis) (2021), a slim, pencil-skirted woman in contrapposto appears to be mesmerising a black cat; her arm reaches out over its head. Unnervingly, the woman appears to have two faces, though this may be a shorthand for motion. The cat, meanwhile, may well be under her spell – its round obsidian pupils look straight out, entranced – but they also connect directly to ours, as if this were a daisy chain of spellbinding. On one level, this is something of a joke about painting – how to make a viewer look, how to keep their attention – but on another the painting, the situation, is endlessly unexplained. It’s not wholly surprising that, in a painting from a few years earlier, the deserted street scene with heightened perspectives and long shadows that is Blind Alley (2016), Andersson explicitly nods to the metaphysical conundrums of Giorgio de Chirico.

Hypnos (Hypnosis) (2021), Mamma Andersson. Photo: Poul Bouchard/Louisiana Museum of Modern Art; courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery and David Zwirner

Blind Alley, like many of Andersson’s paintings, features an unstable mix of textures, some thin and some encrusted, which the viewer’s eye has to hopscotch over. This adds to a germinal sense that her canvases situate themselves in multiple realities at once, and it keeps the observer wrong-footed. One is allowed to feel somewhat easeful – you can generally see what’s going on in one of Andersson’s paintings, they’re spatially comprehensible, they offer familiar forms, their architect is exceptionally skilled at atmospherically muted colour combinations – but never released from a sense that, on multiple levels, they’re barely hanging together, that all is provisional. Often, indeed, that sense feels analogous for something larger, cultural, environmental; but one of Andersson’s greatest gifts as an artist is her refusal to overstep certain lines of connotation. Thanks to her mastery of staging and corralling of instinct, we’re held at the endlessly looping outset of the horror movie, the family driving cheerily through mountains to the Overlook Hotel, or just arrived with friends at that cabin in the woods on a sunny day. In the distance we may hear thunder, or see orange flames on a far horizon. We’re safe for now – but for how long?

‘Mamma Andersson – Humdrum Days’ is at

the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, until 10 October. New works by Mamma Andersson (and Andreas Eriksson) are being shown by Stephen Friedman Gallery at 107 S-chanf, Switzerland, from 6 July–29 August.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.