The editors of the Architectural Review once described it as ‘hacking its own way up the ice-slope of modern experience’. As the 1960s stuttered to a close, the ‘modern experience’ that had impelled national renewal during the post-war era was under assault from social convulsions, technological advances and intimations of a looming environmental crisis. The AR’s response was the Manplan series, aimed at reframing architecture through the broader perspective of society, politics and culture and employing a more direct visual language borrowed from reportage and photojournalism. Conceived by Hubert de Cronin Hastings, the AR’s proprietor and editor-in-chief, Manplan was both a cri de coeur and also a call to arms.

Calculated to provoke and galvanise its largely professional readership, Manplan was urgently questioning and speculative in the tradition of Outrage and Townscape, previous well-regarded editorial campaigns by the AR. It was also a calculated gamble by an ageing actor manager – by then, Hastings was in his late sixties – intended to boost declining subscriber numbers and generate much needed advertising revenue.

Known to his friends as ‘H de C’, Hastings was a mercurial figure, the third son of Percy Hastings, one of the original founders of the AR in 1896. Hastings fils had some architectural training, but was originally employed to maintain a foothold in the family publishing business. Brilliant, if at times eccentric – one short-lived wheeze required editorial meetings to be conducted in masked Arctic battledress so that participants could not be identified – H de C came to preside over the Architectural Press, with its stable of magazines and books, agreeably ensconced in a warren of 18th-century lawyers’ chambers just off Whitehall. There was even a private pub in the basement, the famous Bride of Denmark.

Though the Architectural Review is still in print, the ecosystem that sustained it for so long was dismantled by the minions of Robert Maxwell, when the corrupt media tycoon acquired the Architectural Press in 1990. After Maxwell’s demise, its photographic archive was salvaged and transferred to the RIBA. From this trove of national significance, curator Valeria Carullo has exhumed and collated material to construct a punchy exhibition on the Manplan phenomenon and how it redefined ‘architecture as social space’.

Pepys Estate, Deptford, London: children playing on a raised walkway by Tony Ray-Jones. Photo: Architectural Press Archive/RIBA Collections

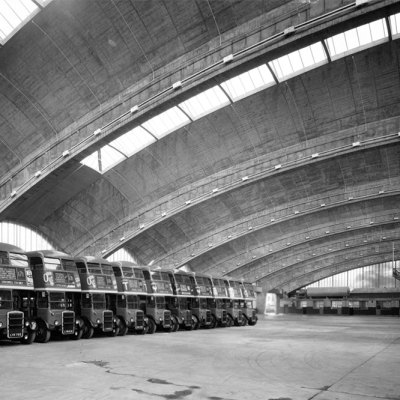

Structured around socially pertinent themes – transport, education, religion – each of the eight Manplan issues had a guest editor (a young Norman Foster edited Manplan 3 on industry) and a roving guest photographer. Among the roster of talented, energetic photojournalists dispatched around the country were Ian Berry, Peter Baistow, Patrick Ward and Tony Ray-Jones. The exhibition emphasises Manplan’s daring departure from the convention of architectural magazines by its pairing of an image of Abbotsinch Airport in Glasgow – perfectly framed and lit, like a studio portrait, and entirely devoid of people – alongside Ian Berry’s view from virtually the same angle, the building simply a backdrop to the experience of those using it.

As the exhibition unspools chronologically through each issue, the work of Manplan’s photographers contrives a vivid insight into late ’60s Britain in all its vigour and pathos. Children cavort around bleak housing estates, workers pose stoically on factory floors, day trippers queue up to view stately homes and commuters exude misery on packed trains. Social inequality is a constant theme – a Rolls-Royce sitting serenely outside a stockbroker-belt Champneys is juxtaposed with the bewildering scrum at an NHS hospital. Crystallising the spirit of the age, the lone vestige of a historic terrace sits like a carious tooth marooned in a landscape terraformed by modernist housing blocks.

More than 50 years later, the images still resonate and the stark monochrome palette adds to the aura of anomie – a special type of ‘Manplan black’ ink was devised to impart extra graphic heft. Manplan covers also featured a succession of delightfully disquieting grotesques based on the human head, from phrenology to anatomical drawings.

The exhibition concludes with an enlarged contact sheet of Patrick Ward’s shots of Blackpool beach, all grim jollification and families huddled around windbreaks, which was to have featured in Manplan 9, putatively devoted to leisure. The original strategy was to publish 20 bi-monthly issues from 1969 onwards, culminating in a manifesto for a ‘Mantown’. However, disagreements within the editorial team – Jim Richards, day-to-day editor of the AR, wanted nothing to do with Manplan – and its apparent failure to revive commercial fortunes, as many readers recoiled from a surfeit of vérité, quietly put an end to its ambitions. Hastings went on to retire in 1973, but not before sacking Richards, leaving a disunited AR to confront the 1970s and the collapse of modernism.

Classroom window in Wales by an unknown photographer. Photo: Architectural Press Archive/RIBA Collections

Often now described as ‘the bravest moment in architectural publishing’, Manplan has a renewed relevance as Britain’s physical and social infrastructures crumble. Yet there is a certain irony in isolating and objectifying images that were once the driving force of a wider editorial and journalistic initiative. Though it’s possible to flick through the Manplan issues on a display screen, the exhibition lacks a sense of the power and storytelling of the original print versions.

When Manplan first plopped through letter boxes, it struck AR readers as either enthralling or appalling. ‘Peter Womersley is cancelling his subscription,’ ran one aggrieved missive; ‘He buys the AR to read about architecture, not overcrowded trains and buses, which he knows about only too well.’ Like many others who sputtered in disgust, Womersley would probably be astonished to discover that Manplan is now the focus of exhibitions, doctoral theses and a new fanbase; few could have predicted that it would have such a rich and persistent afterlife. But architecture is inherently a social art and, amid its radical bravado, Manplan understood that architects disregard this at their peril.

‘Wide Angle View: Architecture as social space in the Manplan series 1969–70’ is at the Royal Institute of British Architects, London, until 4 May 2024.