This review of Marcel Duchamp by Robert Lebel (Hauser & Wirth Publishers) was first published in the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1959, Marcel Duchamp’s career was in the weeds. Not that he minded much. He had largely abandoned making art almost 40 years earlier and, while he still dabbled in corners of the art world, full recognition had never really arrived. Plans for a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York were shelved in the 1940s; talk of another, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art a few years later, fizzled out.

A monograph on Duchamp’s work had never been published either. Which made the arrival, in late 1959, of Robert Lebel’s illustrated monograph on the 72-year-old artist a major event. The then-comprehensive volume, published in both English and French, was the result of nearly a decade of collaboration and conversation between Duchamp and Lebel, a French art historian and critic, collector, former art adviser and gallerist who had been involved with the Surrealist movement in the 1940s. Its budget of $32,000 ($10,000 of which came from the artist and patron William N. Copley) was then, as it is now, a significant sum.

A monograph on Duchamp’s work had never been published either. Which made the arrival, in late 1959, of Robert Lebel’s illustrated monograph on the 72-year-old artist a major event. The then-comprehensive volume, published in both English and French, was the result of nearly a decade of collaboration and conversation between Duchamp and Lebel, a French art historian and critic, collector, former art adviser and gallerist who had been involved with the Surrealist movement in the 1940s. Its budget of $32,000 ($10,000 of which came from the artist and patron William N. Copley) was then, as it is now, a significant sum.

The French edition, Sur Marcel Duchamp, was published by Trianon Press and went through several printings. Grove Press’s English edition, however, soon went out of print, despite Duchamp’s growing popularity in the 1960s and ’70s. The book became highly sought after, until it was superseded by a number of other biographies and catalogue raisonnés, including Arturo Schwarz’s The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, published in 1969, and Calvin Tomkins’ biography of 1996.

It took nearly another decade of conversation and collaboration for a new edition of Lebel’s Marcel Duchamp to be produced by Hauser & Wirth Publishers, with the involvement of the author’s son, the artist Jean-Jacques Lebel, the Association Marcel Duchamp and the collector Harald Falckenberg.

The book is a time capsule, an astonishingly exacting facsimile of the Grove Press original. The blurbs on the jacket flaps include one from Salvador Dalí, and the price is still printed as $15. The designers, London-based fluid, recreated the original typefaces as digital fonts, then placed each letter and image exactly where it is in the original. They fretted over paper choices: should they approximate the colour of pages as they were in 1959, or match their yellowed condition as they are today? When they discovered text changes, presumably inserted mid print-run, which version should they use? To which end of the run should they refer for tonal correction on the seven tipped-in colour plates?

As a result, the new reproduction is less functional than was the original. Most of the soft, greyscale reproductions of paintings are of little use to a contemporary reader with access to Google Image Search. Captions are untranslated, as in the original – although translations do appear in the ‘catalogue-raisonné’ section, which is of course poignantly incomplete, omitting as it does Duchamp’s final, secret work: Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, 2. Le gaz d’éclairage… (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas…) of 1946–66, which was unveiled to the public in 1969, nine months after Duchamp’s death and to the chagrin of many Duchampians. Today, any analysis of Duchamp’s oeuvre feels imbalanced without a discussion of this work. (‘There have been no changes of direction in Duchamp’s life,’ Lebel declares early on, inadvertently throwing his critique under a bus.)

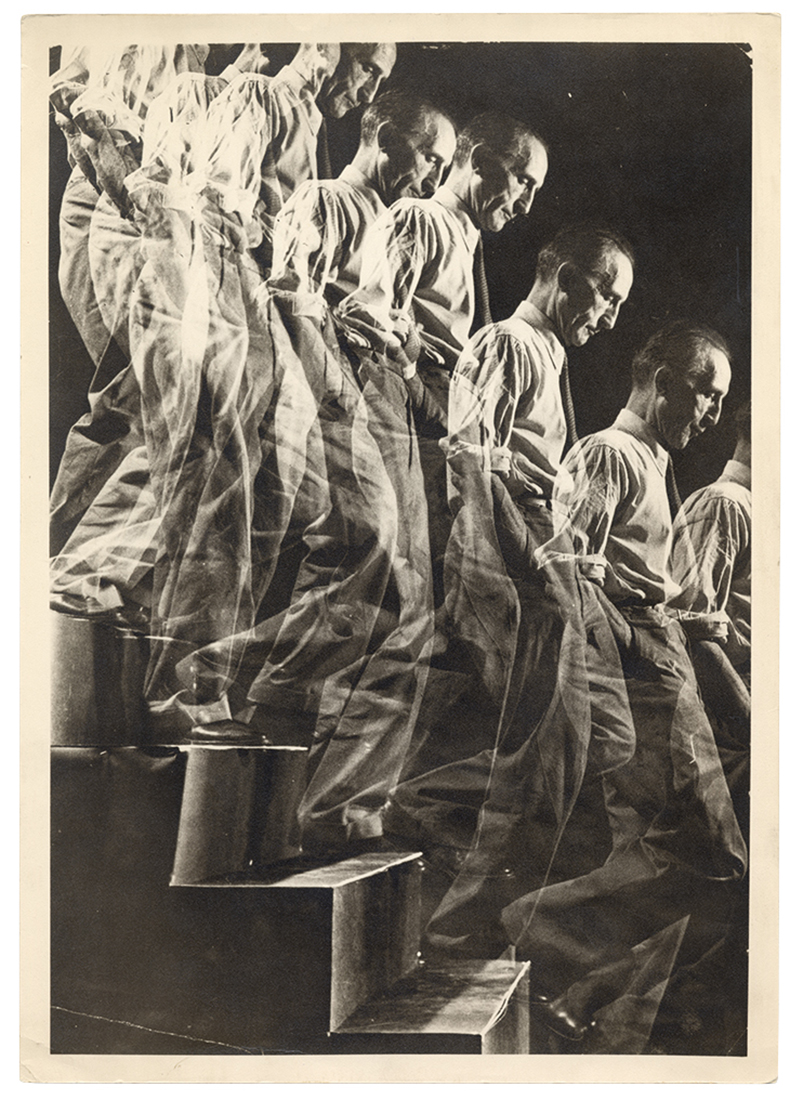

Marcel Duchamp descends staircase (1952), Eliot Elisofon, reproduced in Life magazine. Courtesy Marcel Duchamp Archives, Paris; © Eliot Elisofon/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Lebel’s writing is gentlemanly, fond and fastidious. Calvin Tomkins has called it occasionally ‘rather windy’; he also admits that the book’s publication in 1959 gave him his first opportunity – as a cub reporter for Newsweek – to interview Duchamp, at a time when he knew practically nothing about the artist. For the most part, Lebel follows a biographical structure (‘for which we apologize’), then devotes a chapter to a close analysis of The Large Glass, despite conceding that Duchamp ‘took every precaution to see that nothing of [his work] should be intelligible to an outsider’.

Also included is a transcription of a lecture Duchamp delivered to the American Federation of Arts in Houston in 1957, and contributions from Duchamp’s friends Henri-Pierre Roché and André Breton. Finally, Lebel appends a text on the theme of humour in Duchamp’s work, which he regrets has not found its way into the main body of the book.

Hauser & Wirth’s slipcased edition comes with a softbound supplement, which pads it out with some historical context and background. In a slightly mystifying act of editorial indulgence each of the essays – by Michaela Unterdörfer, Jean-Jacques Lebel and Michael R. Taylor – quotes the same passage from the Houston lecture: ‘All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his own contribution to the creative act.’

Duchamp was famously laissez-faire about the interpretation of his work. When, in 1968, Arturo Schwarz expounded a theory of the artist’s incestuous desire for his sister Suzanne, Duchamp seemed enormously entertained. Despite his close involvement, it is therefore not quite right to consider this an ‘authorised’ monograph. Lebel’s views are entirely his own – as are Roché’s and Breton’s.

Nevertheless, Duchamp’s fingerprints are all over the 1959 edition, a fact that explains the designers’ care to retain them in their new version. His signature, for instance, is reproduced in a handwritten note even before Lebel clears his throat; portraits – some photographed, others sketched, painted or sculpted by his friends – fill several pages. The cover image, which Duchamp apparently cut out himself with a pair of scissors, features the artist’s hawkish profile, double-exposed with a less familiar image of the artist smiling: a kindly uncle, a mischievous co-conspirator. As is the case throughout this charmingly musty book, a more fully rounded, humanised Duchamp emerges from within his trademark silhouette.

Marcel Duchamp by Robert Lebel is published by Hauser & Wirth Publishers.

From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.