From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Even for an artist as widely feted as Richard Avedon, 2023 has been a banner year. One hundred years after his birth (he died in 2004 while on assignment), a series of exhibitions has been launched to celebrate his long, prolific and influential career. In May, art imitated life as New York’s best-dressed filed in to the Karl Lagerfeld-themed Met Gala, while Avedon’s celebrated Murals hung decorously nearby. Earlier this year, ‘Richard Avedon: Relationships’ showed at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, while the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth visited ‘Avedon’s West’. And, at the beginning of May, ‘Avedon 100’ opened in the Chelsea branch of Gagosian Gallery in New York (until 24 June). The show and accompanying catalogue capture Avedon’s prodigious output with evenhandedness, while suggesting several favourites. Among these is the haunting but frequently misunderstood portrait Avedon made of actor, model and film-production pioneer Marilyn Monroe in 1957.

The gallery invited some 150 curators, artists, sitters, collectors and critics to contribute to the catalogue, including François Pinault, who suggests that with his portrait of Monroe, Avedon captured ‘a substantive truth of his subject beyond what was visible’. Gallerist Larry Gagosian also weighs in: ‘Because she looks melancholy, and also because she would die less than five years after it was taken, it’s often called “Sad Marilyn”,’ he writes. ‘For me, the most appealing part of this work is the notion that we are watching two legends at the peak of their powers: Avedon behind the camera and Marilyn in front of it.’ This is true, but what distinguishes the picture is not so much mutual accomplishment as mutual sympathy, as photographer and subject wrestle with parallel notions of fame, celebrity and self.

Marilyn Monroe, actress, New York City, May 6, 1957 Marilyn Monroe, actress, New York City, May 6, 1957

Avedon portrays Monroe as a wistful, distant figure – eyes lowered and fixed on the distance, one brow gently arched, and shoulders slumped. Through Avedon’s lens she has become a fallen angel: down, even absent; contemplative, yet drained. Outwardly, she remains instantly recognisable, swooping curls of blonde hair pulled back to reveal her widow’s peak, pencilled eyebrows and dark mascara, mole visible on her left cheek, and glossy lipsticked lips slightly pursed to reveal two barely perceptible buck teeth. Here such artifice loses much of its allure, heightening the contradiction between the actress’s public appearance and her private self. The real Monroe is clearly stronger, deeper and more complex than her persona, yet her emotional state is hard to read. Is she simply tired, worn down or stressed? Is she lost in thought, or trapped in some dark existential labyrinth?

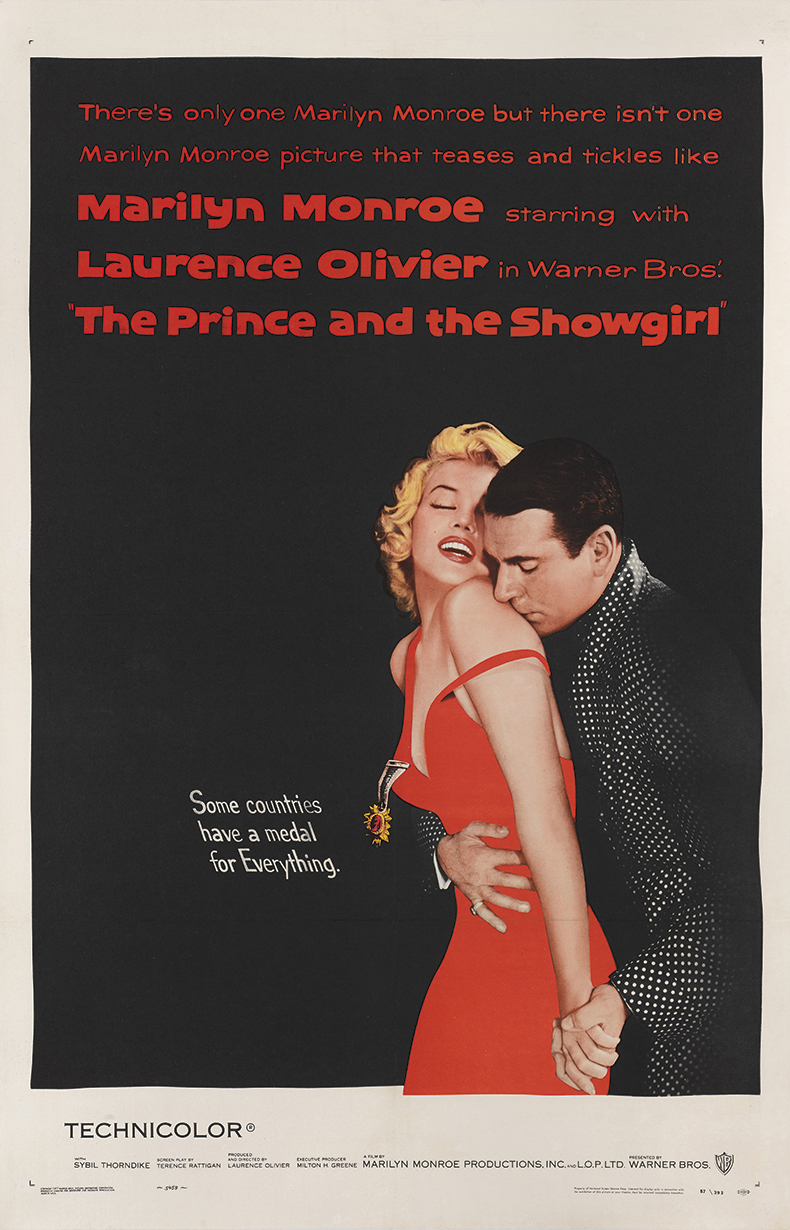

The famous photograph was one of a number made on 6 May 1957, when – still only 30 years of age – Monroe arrived at Avedon’s studio on Madison Avenue to pose for publicity shots for her new romantic comedy, The Prince and the Showgirl. She wore a favourite dress – a shimmering plum-coloured sequinned gown with plunging neckline, which she had also worn to the premiere of Baby Doll the year before and more recently at the Waldorf-Astoria’s annual ‘April in Paris’ charity ball.

Poster for The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), starring Marilyn Monroe and Laurence Olivier and produced by Marilyn Monroe Productions. Courtesy Sotheby’s

At this point in Monroe’s career, hit movies such as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Bus Stop (1956) had brought her superstardom, but her professional and personal life were in transition. Her short-lived union with baseball star Joe DiMaggio had broken down, and in 1956 she married her third husband, playwright Arthur Miller. Around the same time, her contract with Twentieth Century-Fox expired, resulting in a drawn-out public dispute. The Prince and the Showgirl was to be the first project of the production company she created, Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP).

The structure and responsibility of managing an independent production may have been new to Monroe, but acting was well within her comfort zone. Publicity stills were a routine part of the process, and the photographs Avedon made during the first part of his session with Monroe showed her in the sort of playful, provocative poses that audiences had come to expect. It was only towards the end of the sitting that her mood shifted. Avedon continued to photograph her until Monroe seemingly dropped her guard, providing a glimpse of the circumstances of her life and the woman behind the public persona that she had adopted.

From the outside looking in, at the time of Avedon’s photograph, Monroe had reason to celebrate. After her contract with Twentieth Century-Fox expired in 1955, she demanded, and eventually got, unprecedented control over her film career. Under pressure from a Supreme Court ruling against industry practices in 1948, and the new and increasingly popular medium of television, the rules that had governed Hollywood for decades were, by the time she sat for Avedon, in upheaval. The studio system under which the industry was organised for the first half of the 20th century permitted motion picture studios to ‘own’ actors under long-term contracts, giving them sweeping authority over the films in which they would appear, the roles they would play and the directors, writers and cinematographers with whom they were teamed. Now the system was breaking down, forcing studios to cede power and increasingly allowing stars to dictate the terms of their employment.

In early 1955, Monroe insisted that because Fox had not fulfilled all its terms, their contract was void, and she refused to perform again until the studio agreed to a new deal. Fox resisted, but ultimately had little choice but to re-sign their most bankable actress on her terms. Under the new agreement, she would appear only in A-list films, and would have a veto over the directors and cinematographers she worked with. Her salary rose to $100,000 per film – more than $1m in today’s money. At the same time, she obtained the right to work with other studios and independent producers. This enabled her to strike out on her own, founding Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP) with her friend the fashion photographer Milton Greene in 1955. The Prince and the Showgirl would become both the first and last film the fledgling company produced.

Marilyn Monroe photographed in March 1955 by Milton H. Greene, with whom she founded her production company. Photo: © 2023 Joshua Greene/Iconic Images

Despite the easing of industry constraints, by the mid 1950s it was still rare for any American actor, especially a woman, to create their own production company. While in the long run Monroe’s victory would contribute to the downfall of the studio system; in the short term the bitter and widely reported conflict between her and Fox had taken a toll, and the new company foundered. As the situation worsened, quarrels erupted between the two principal partners, Monroe and Greene. By April 1957, Arthur Miller had become increasingly involved, and Monroe and Greene parted ways. Although he was an accomplished photographer in his own right, with the collapse of their partnership Greene was not a realistic candidate to take the publicity pictures. So Avedon, chief photographer for Harper’s Bazaar and a regular contributor to Vogue, Life and Look, among other magazines, was given the job.

It is tempting to read these aspects of Monroe’s biography into Avedon’s portrait – the uncertainty and strain of her battle with the studios, the threats and ultimatums she must have endured, and the inevitable blows to her self-confidence. Her difficult love life, only recently stabilised with her marriage to Miller, may also have weighed on her. As head of her own production company, Monroe had to make both creative and financial decisions, raising money while keeping a firm grip on the budget and ensuring the picture paid off at the box office. Avedon’s session was a key milestone on the way to achieving financial success.

Even as he photographed Monroe, Avedon was experiencing dramatic changes of his own. A comedy based loosely on his life, Funny Face, had been released a little over a month before the Monroe sitting, on 28 March 1957. A week after he made his famous photograph, it would be shown at Cannes. The movie starred Audrey Hepburn as reluctant model and love interest of a fashion photographer played by Fred Astaire, with music by George and Ira Gershwin. Since Astaire’s character was modelled on Avedon and he had been involved in its production, it brought unprecedented attention to the photographer and his work. The photograph was more than just a portrait of the famous actress. It carried an element of self-portraiture, too.

Given the nuance of Avedon’s picture, and considering it was never used as a publicity shot for the film, its status as an advertising or fashion photograph is open to question. Such questions have become increasingly quaint, in part because of Avedon’s genre-bending work. As the field has matured, and as consumers have become increasingly canny about industry practices, photographers have come to interpret their briefs in surprising ways, testing the boundaries between art and commerce. Avedon was at the forefront of those who challenged the distinction between commercial and art photography, exhibiting his work in museums and galleries while at the same time publishing in magazines.

Avedon later recalled that Monroe began the session on 6 May by sipping wine and ‘dancing, singing and flirting’ for hours in the studio while they attended to the publicity shots, which Avedon initially photographed in colour. Eventually, he would say, her energy subsided and she withdrew quietly to a chair in the corner, virtually expressionless. It was then that Avedon claimed to have taken the photograph. The celebrated picture was evidently not quite as spontaneous as he suggested, since a number of variant exposures are preserved in the Avedon Archive. However, the fateful picture does contain clues reinforcing his account that it was made away from the main studio set-up. The light is full but soft, as if Monroe is positioned away from the direct glare of the studio lamps. Only tiny spots of reflected studio light (known as catch light) are visible in each eye.

During the session Avedon almost certainly used strobe lights, with which he had begun experimenting at this time, and which later became his stock-in-trade. Strobes provide extremely brief, high-intensity flashes of light, and since they fire faster than a conventional shutter mechanism can open and close, it is the burst of light that controls exposure rather than the camera shutter. This is the same kind of lighting used by scientists to record rapidly occurring action, as when MIT engineer Harold Edgerton famously photographed a bullet passing through a playing card, or the coronet briefly formed by a drop of milk. In Avedon’s case, it enabled him to photograph exceedingly narrow slices of time in the studio – behaviours and expressions occurring so quickly as to be invisible with the naked eye. Consequently, in Avedon’s photograph Monroe’s expression is impossibly fragile, suspended in surreal transience, as if sandwiched between inescapable layers of time. In fact, it is a moment so fleeting that it is beyond the threshold of unassisted vision.

Strobe lights also fire more quickly than the pupil can dilate, enabling Avedon to obtain the uncanny effect of fully illuminating Monroe’s head and torso while her eyes still form deep pools. Their darkness contributes to her impenetrable expression, like windows into night. The ambiguity of the picture is central to its magnetism. Here is the actress in suspended animation, frozen between success and failure, levitating between fatigue and sadness. With her eyes averted, head angled slightly and lips gently parted, she seems almost about to speak. At the same time, the uncanny details of her face and figure frozen in time ground the picture, rescuing it from hollow artificiality or caricature. The sequins at her breast dissolve into circles of light, equal and opposite to the shadows of her eyes. In Avedon’s hands they become timeless, celestial.

The thin veneer of glamour momentarily lifted, Avedon found not only a compelling individual but also a person trapped in a predicament she felt powerless to escape. She was aware that she had become a commodity – a consumable entity to be used for profit by the business establishment. While she understood this, and attempted to control it, she would eventually succumb to its pressures. Yet for one brief instant – one fraction of a second in time – the whole story in all its complexity was exposed. Sad? We may never know. But she was utterly, unmistakably human. And so was Avedon.

‘Avedon 100’ is at Gagosian Gallery, New York until 7 July.

From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.