In Greek myth, Cerberus is the three-headed guard dog at Hades’ gates, keeping the dead firmly down. The symbolic beast has lent its name to Mark Bradford’s first solo show at Hauser & Wirth in London, which peers into hellish modern America: a cracked empire of punitive authority, tightly policed race and class boundaries and entrenched inequality.

These new works, all made in the past two years, mark a break from Bradford’s typical style: geometric grids mapping layers of abstraction. Here, the works roar from the pristine white walls of the gallery space. There are strobes of colour – the fiery palette of an inferno, bloodstain reds, splotches of turquoise – that move across the canvases like sunspots, or the first throb of a migraine. The notion of colour blindness is one that Bradford continuously circles around. Who is forced to ‘see colour’, and who is in a position to pretend it doesn’t exist?

Gatekeeper (2019), Mark Bradford. Photo: Joshua White; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Mark Bradford

Gatekeeper (2019) looks like an aerial view of a fractured planet, shot through with coral pink and oasis blue. Tangled wires resemble fallen power lines: everything disastrously off-grid. Any threat depends on proper behavior (2019) – its title typical of Bradford’s pummelling approach – is a study in murky opalescence, with the polluted sheen of a dirty river. It’s a modern Styx roiling through the pitiless cityscape of Los Angeles.

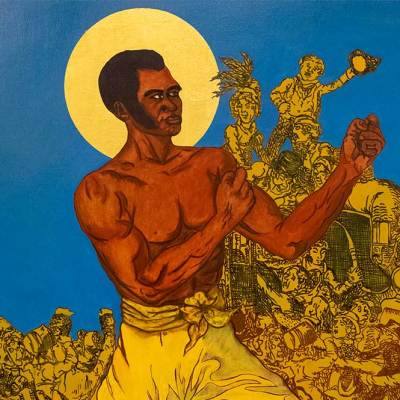

Los Angeles is both Bradford’s birthplace and muse, its poverty and gaudy wealth making it emblematic of the modern city as a chasm of inequality.The work from 2018 which shares the exhibition title is its centrepiece: as sprawling and incendiary as the metropolis itself, a chaotic scrawl of dispossessed energy. Dominating almost an entire wall, it’s snarled up with bits of rope, the letters of a disintegrating alphabet ripped from posters, and unrecognisable pieces of detritus scavenged from the streets. In A five thousand year old laugh (2019), lines are scored angrily into the brooding, overripe surface of the canvas. What seems armoured about these paintings on first glance is actually evidence of their fragility: clumps of paper are thrown like rocks, denting every surface.

Cerberus (2018), Mark Bradford. Photo: Alex Delfanne; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Mark Bradford

The works themselves are frameless, slathered on canvases that still bear the handwritten scrawls of their dimensions. In them, Bradford reads the landscape – both geographic and sociopolitical – through the prism of his own ‘otherness’ as a black gay man raised in a predominantly white district of South Los Angeles. Indeed, the question of ‘readability’ is at the heart of Bradford’s densely layered work: which narratives can be read on the surface of things? Which types of looking are sanctioned and which are automatically perceived as a threat?

But there’s something impenetrable about these teeming lumps of matter, too: an inner core they’re unwilling to give away. Is there a secret to be disclosed beneath the chaos; all this monumental, aggressive style? Or is Bradford suggesting that this kind of collapse – everything levelled to the same ruinous proportions – merely mirrors the reality of our fractured global moment?

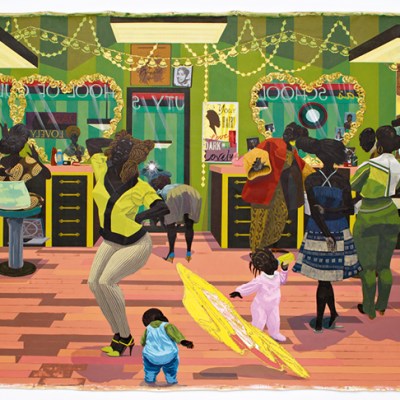

Dancing in the Street (video still; 2019), Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Mark Bradford

In Dancing in the Street (2019), the video for the pop song recorded in 1964 by Martha and the Vandellas is projected at night across LA’s chainlink fences and graffitied walls. The song was invoked as a civil rights anthem during the Watts riots a year later, when thousands of African-Americans took to the streets, resisting police brutality and institutionalised racism.

These flickering, ghostlike frames offer an eruption of the past into the present, freighted with a melancholy and renewed desolation for how far the struggle has left to go. The uneven audio temporarily amplifies and then fades away. The song’s voices shimmer with hope, but who – on these ravaged streets – is still listening?

‘Mark Bradford: Cerberus’ is at Hauser & Wirth, London, until 21 December.