While nothing that Shakespeare wrote could exactly be called ‘little known’, his two narrative poems – Venus and Adonis and its knotty companion piece The Rape of Lucrece – have, somehow, ended up as unofficial ‘minor works’. Read for the most part only by academics, diligent undergraduates, and diehard fans, Venus and Lucrece languish at the bottom of a list topped by the most famous of the plays, and the sonnets.

Turn back the clock four centuries, though, and the opposite was true. When Venus and Adonis was published in 1593, Shakespeare was just another jobbing dramatist on a crowded scene. Seven plays into his career, he was successful enough to attract the jealousy of at least one fellow writer – the now famous ‘upstart Crow’ jibe levelled in Greene’s Groats-Worth of Wit (1592) – but his future was hardly bright. Thanks first to disputes with the authorities, followed by a violent outbreak of plague, the playhouses were shut almost continuously from June 1592 to June 1594. If Shakespeare did have anything like a devoted audience, he had no access to it, and – with none of his plays yet available as printed books – it had no access to him either.

Sometimes necessity really is the mother of invention. Cut off as Shakespeare was from his normal audience and income, Venus and Adonis appears to have been his version of a get-rich-quick scheme. Cashing in on a trend for mini-epics – epyllia, to give them their rather lovely technical name – on Ovidian subjects, he appears to have written the poem not just to sell it to his printer, but as a calculatedly ‘literary’ public bid for the attention of its noble dedicatee. One of the best-known patrons of the era, Henry Wriothesley (‘Risley’), Earl of Southampton, was exactly the kind of friend a poet would want in a time of need.

There is no evidence to say how impressed Wriothesley was, but either way Venus was a hit. By 1640, it had gone through 16 editions; by comparison, the Sonnets, published in 1609, had only two editions by the same date. In the wake of Venus, Shakespeare suddenly had a reputation; and in contemporary praise of the ‘mellifluous and honey-tongued’ poet, it is almost always Venus and Lucrece that figure first. The poem even seems to have brought into being the Shakespeare fan as a recognisable stock figure. An academic play from the opening of the 17th century features one: young, lovesick, pretentious, he keeps a picture of ‘sweet Master Shakespeare’ in his study, and sleeps with a copy of Venus under his pillow.

Reading Venus, it is easy to see why it was a hit. With an eye on Wriothesley’s tastes, it is learnedly classical and rhetorically complex, and, at the same time, borderline pornographic. It retells the myth of the goddess of love’s affair with the beautiful young Adonis, but with some radical changes. Shakespeare’s version is rewritten around what might be dubbed a mytho-logical impossibility: the goddess of love getting snubbed.

The result is a kind of serious gag, with Venus transformed into a cougarish giantess, desperate to bed a ‘tender boy / Who blush’d and pouted in a dull disdain, / With leaden appetite’. Tall enough to ‘pluck [Adonis] from his horse’ and tuck him, literally, under her arm, she straddles and kisses him, invites him to explore the ‘Sweet bottom-grass’ and ‘Round rising hillocks’ of her body, and even plays dead in hopes that he will kiss her. Irritated and immune to her advances, Adonis eventually disentangles himself, and heads off to the hunt, where he is killed by a boar, that, with hefty symbolism, gores him in the groin. Out-Oviding Ovid, Shakespeare then gives two aetiologies at once: the origin of the anemone, sprung from the blood of Adonis, and the origin of all mankind’s problems in love, as the grieving Venus swears that ‘Sorrow on love hereafter shall attend’.

Venus insists (2015–16), Marlene Dumas in Venus & Adonis (2019; David Zwirner Books). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © Marlene Dumas

The selling point of the edition of Venus from David Zwirner Books, annotated and paired with a new Dutch translation by Hafid Bouazza, is a suite of 33 ink wash illustrations by the South African-born, Netherlands-based artist Marlene Dumas. In theory, Dumas and Venus are a match made in heaven. Focused on the physical interactions between bodies, and on an obsessive circling around red, purple and white as it toys with purity, lust and death, Venus is an intensely visual poem. Dumas has often drawn on pornography as source material for work that examines sexuality, asking how we can, or cannot, ‘distinguish between love and lust’ from visual evidence alone. Indeed, of the few illustrators that have attempted it – Roger Grillon, André Hofer, Horace Walter Bray, and Rockwell Kent – Dumas is the best suited on paper.

Individually, some of the plates are superb. In the fourth, Venus straddles a supine Adonis, her arms and haunches symmetrically caging his body with an energy and line that recalls Picasso’s Vollard Suite etchings. In another, the goddess covering her eyes and screaming into the sky dissolves into watery blotches, anchored only by the black hole of her mouth. But there is something vague about Dumas’s responses too: a conventionality to her images of the callipygous goddess with flowing hair and the frowning hunter with tousled curls that seems like a failure to respond to the poem’s unconventional specifics. Overall, differently sized, graphically inconsistent, scattered unevenly through the text, the plates feel less like a coherent suite of illustrations than a sketchbook: three passes at the boar, two at an owl; a snail plucked from a simile.

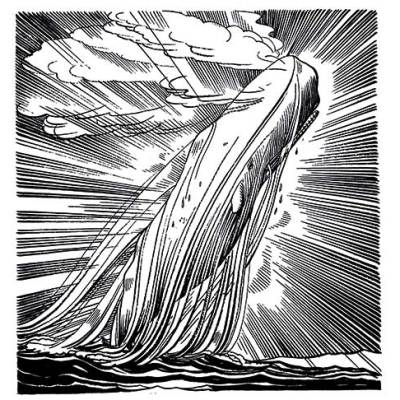

I do not envy Dumas the task – especially on her first foray into illustration as such. But, finally, despite the occasional flashes, her work here neither feels like it adds to the poem or like it stands on its own two feet. It made me, above all, wish for a new edition of the Rockwell Kent engravings. His stylised combination of art deco and Attic-vase line comes closer by far to plugging the poem’s feeling of distorted classicism and stymied eroticism – the odd verve that helped it make Shakespeare’s career.

Venus & Adonis, illustrated by Marlene Dumas, is published by Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep/David Zwirner Books.

From the October 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.