Two mirror-image manikins, one dressed in a blue Victorian gown, the other covered in a mélange of purple tassels, stand freeze-framed, suspended in time. Each woman has one arm drawn in front of her chest in defence, ‘or to give you a backhand’ laughs their creator, young South African artist Mary Sibande.

The two costumed manikins form an imposing installation. They stand on a raised stage, surrounded by an abstract scene of hanging purple objects. The resulting tableau, A Reversed Retrogress (2013), will be the final thing you see in the British Museum’s landmark winter exhibition, ‘South Africa: The Art of a Nation’, opening 27 October. Sibande’s manikins are an arresting part of what promises to be an edifying survey. The exhibition comes hot on the heels of a record-breaking South African art sale at Bonhams London in September, and Somerset House’s more recent 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, where South African art was well represented by AFRONOVA (Johannesburg) and Barnard Gallery (Cape Town). As this increased UK attention suggests, the popularity of South African art overseas is growing. Sibande’s sculptural mise-en-scène, positioned pride of place in the British Museum, is at the very forefront.

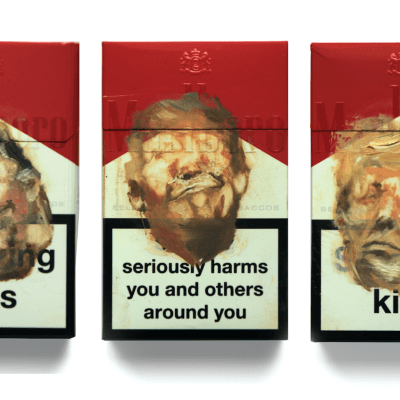

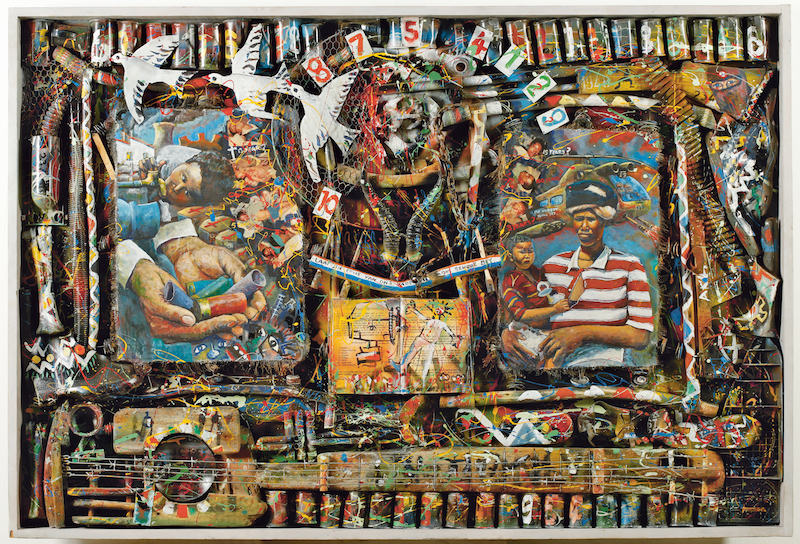

Transition (1994), Willie Bester (b. 1956). Private Collection; © the artist (On display in ‘South Africa: The Art of a Nation’ at the British Museum, London, from 27 October–26 February 2017)

‘The concept behind this installation started a few years ago,’ Sibande explains. ‘I wanted to pay homage to the women in my family who were all maids. When you look at the history of South Africa, women didn’t have a choice. They were discriminated against, firstly because they were women, and secondly because they were black.’

Representing black, South African women manifests itself throughout Sibande’s decade-long practice in the form of her alter ego, ‘Sophie’. Although never seen before in the UK, ‘Sophie’ has featured in a number of displays: at the 2011 Venice Biennale, in Paris Photo the same year, and in a host of African and European exhibitions, including an artistic residency in 2013 at the MAC/VAL Museum of Modern Art in France. ‘Sophie is inspired by my great grandmother,’ Sibande explains. ‘Her masters couldn’t be bothered to learn her African names, so they just called her “Elsie”. During apartheid, it was compulsory for a black child to have a Christian name, hence my name, “Mary”. “Sophie” was born from this law, as a way for me to stop this story from going stale.’

A Reversed Retrogress: Scene 1 (The Purple Shall Govern) (2013), Mary Sibande. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery MOMO; © Mary Sibande

In A Reversed Retrogress, as in many of Sibande’s works, Sophie undergoes a transformation, shaking free from the shackles of her traditional garb and stepping into the wild fashions of her imagination. We travel with Sophie, witnessing the struggles this journey entails. ‘That’s why these two figures are in a violent stance,’ Sibande explains. ‘Change is a violent process.’

Sophie’s dream world is a strange and beautiful place. Sibande wanted to be a fashion designer growing up and was a keen reader of international style magazines which, she tells me, ‘all came from overseas’. Suspended above the manikins’ head is a chandelier of sculptural blobs, reminiscent of Louise Bourgeois’ hanging fabric sculptures from 1996, or John Galliano’s 1990s fantasy couture. Sibande refers to these sculptural elements as ‘teddy bears’, ‘embryos’ and ‘non-winged ceiling beings’. Made from the same royal purple as the dress, these stuffed objects flock around the manikin’s head, giving an aura of familial protection. ‘They’re her army. They go with her everywhere. In a way, they’re like her babies, but it’s almost as if they’ve given birth to her. That’s the whole point of my art – it’s about progress, but about moving forward in a backwards way.’

Mary Sibande. Photo: Adam McConnachie; Courtesy of Mary Sibande and Gallery MOMO

This idea of the slow slog of progress speaks to Sibande’s use of the colour purple, which references the anti-apartheid protesters who marched on parliament in September 1989, in what is today known as ‘The Purple March’. The protestors staged a peaceful sit-in following declarations that the march was illegal; in reaction, the police sprayed the thousands of Mass Democratic Movement supporters with purple dye using a large water cannon, making them immediately recognisable and easier to arrest at a later time.

Sibande explains how these harrowing events have etched themselves into the country’s artistic narrative. ‘South African artists have a lot of content to dismantle. We ask ourselves, “Why did apartheid happen? Where am I after apartheid? What does it mean to be a black woman in South Africa today?” These questions become bricks in a house that artists build around themselves.’

This line of questioning has produced a rich tradition of contemporary art, and Sibande counts contemporaries such as Tracey Rose and Nicholas Hlobo as key inspirations. With help from blue-chip South African galleries like Stevenson, Goodman, and MOMO (who represent Sibande), the global audience is engaging ever more with these pioneering artists. MOMO’s mission statement uses the word ‘international’ five times; Goodman Gallery are marking their 50th anniversary with a major international conference in November, in association with a string of renowned American institutions. As Sibande puts it, ‘these galleries are part of the global narrative – and global economy.’

A Reversed Retrogress: Scene 1 (The Purple Shall Govern) (2013), Mary Sibande. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery MOMO; © Mary Sibande

Despite this, each gallery’s raison d’etre remains the South African story. Sibande’s work often has an intensely personal narrative at its heart, but it’s also one that skillfully references South Africa’s wider history. Hers is a story of feminism, fashion and rebellion – a family tale that Sibande traces back to her great grandmother – but into which can be read a globally relevant, painful truth. But Sibande’s work also represents hope. ‘I’m trying to tell a sad story in a happy way,’ the artist concludes, turning her attention towards the installation. ‘You might see these two women as fighting, but they’re also dancing. It is a celebration.’

‘South Africa: The Art of a Nation’ is at the British Museum, London, from 27 October–26 February 2017.