Writing for the New Statesman in 1953, the artist Patrick Heron described Matthew Smith (1879–1959) as ‘easily the most important English painter of his generation’, one who ‘understands […] the true potentialities of colour’ in a way that makes his art seem ‘more French than English’. An exhibition at Charleston in Lewes, ‘Matthew Smith: Through the Eyes of Patrick Heron’, places the work of these two British colourists side by side to explore what bound them together.

Typically lauded as the inheritor in Britain of Post-Impressionist techniques, particularly the swift brushwork and vibrant colour palette of the Fauves, Smith achieved critical and commercial success during his lifetime, twice representing Britain at the Venice Biennale (in 1938 and 1950). ‘He seems to me to be one of the very few English painters since Constable and Turner to be concerned with painting,’ wrote Francis Bacon; ‘that is, with attempting to make idea and technique inseparable […] so that the image is the paint and vice versa.’ Smith left his mark on Patrick Heron, whose paintings reveal not only the same striking use of colour, but also an appreciation of how colour interacts with – and even ultimately determines – space and form.

Blue Painting with Discs – September 1962 (1962), Patrick Heron. Photo: © The British Council; © Patrick Heron Trust/DACS 2024

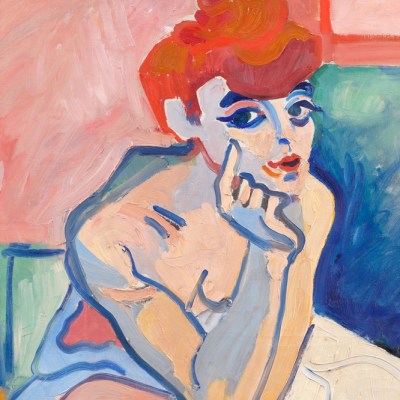

Evidence of Smith’s bold use of colour is immediate. Flowers in a Vase (1914), an early still life, reveals a rapid arrangement of bright yellows, pastel lilacs, scribbled pinks and vivid greens, and a dazzling rush of shapes and shades. Introducing a catalogue of the artist’s works at the Tate in 1953, John Rothenstein calls Smith ‘a colour-intoxicated man’. This intoxication certainly owes something to Henri Matisse, with whom Smith studied at Matisse’s short-lived school in Paris around 1910. While Smith met the French artist on only three occasions, the influence of Matisse’s work on paintings such as Fitzroy Street Nude, No. 2 (1916) is hard to ignore; the high contrast of yellows and shadowy greens creates a striking chiaroscuro reminiscent of Matisse’s Fauvist portraits, while Smith’s chosen palette echoes several paintings by the Frenchman, not least The Pink Studio (1911).

Although Matisse’s influence is most pervasive, Smith also seems to draw upon the work of other experimental painters. There are pointillist touches in paintings such as Fruit in a Dish (1919), suggestive of still lifes by Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. Elsewhere, as its title self-consciously indicates, Landscape Aix-en-Provence (1937) reckons with the legacy of Paul Cézanne, taking on the boulders, trees and open skies that occupy the artist’s paintings of the region. At times there is an almost forensic quality to Smith’s canvases, as though he were conducting a series of painterly experiments, trying to figure out not only what these French painters are doing but also how exactly they are doing it.

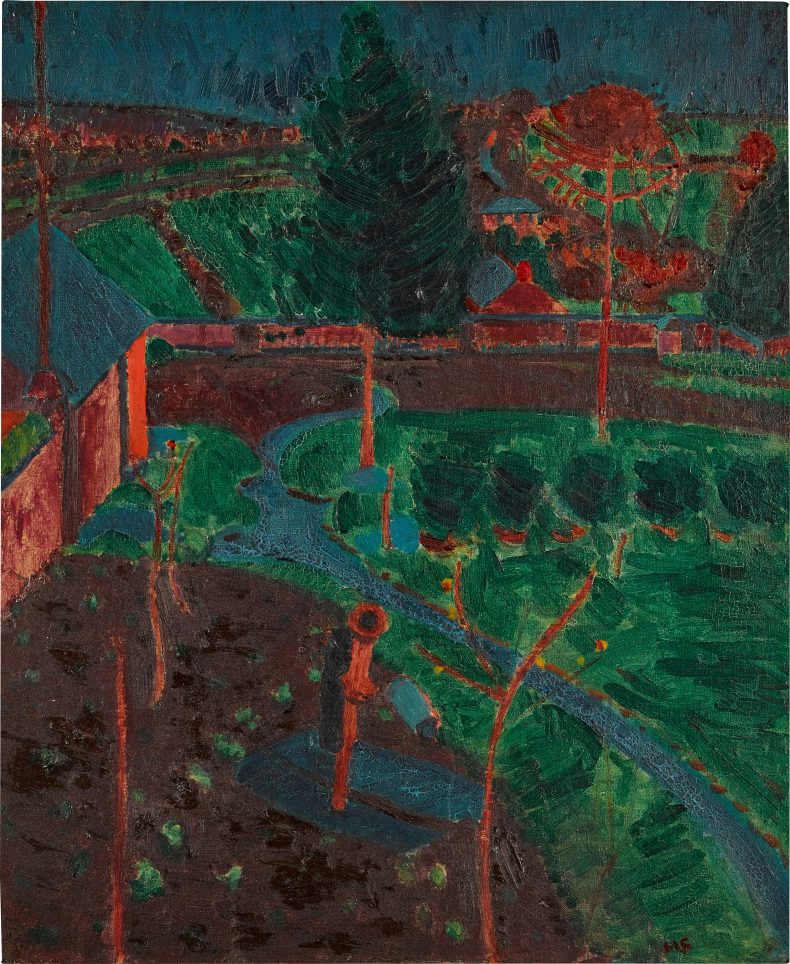

Cornish Garden with Monkey Puzzle (1920), Matthew Smith. Private collection. Courtesy Sam Berwick; © Estate of Matthew Smith

In one sense, Smith’s adventures in colour seem a response to the oppressive muddy landscapes of the First World War, as recorded in the browns, khakis and ochres of Paul Nash’s paintings of the Western Front – see Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood (1917). Smith served during the war and was badly wounded at Passchendaele; after returning to England, he suffered from chronic shell shock, for which he was treated at the Clinique Valmont in Switzerland in 1922. Despite his vibrant palette, Smith’s paintings often carry a sense of disturbance or agitation. His Cornish landscapes – painted in 1920 while he was living in the village of St Columb Major – present a series of uneasy scenes, empty of people, whose ominous clouds and wind-blown trees are rendered in rich purples, mauves and forest greens, bathed in strange nocturnal light, seeming to glow and vibrate. There is something frenetic, uncomfortable, even threatening about the paintings. As Bacon concludes, Smith’s handling of colour often amounts to a ‘direct assault upon the nervous system’.

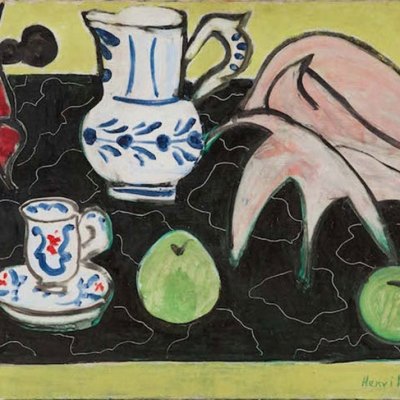

There are only four Patrick Herons on display, which makes it difficult to draw detailed comparisons. There is certainly something of Smith’s energetic application of paint and diagonal compositions in paintings such as The Jardiniere (1948), but the exhibition simply doesn’t show enough of Heron’s work to make the case properly. At the very least, there is more to say about Heron’s leap into abstraction: one senses his interest in Smith’s use of colour as a kind of geometry, for instance, and the space and the depth it creates, though this goes largely unexplored.

The Jardiniere (1948), Patrick Heron. Private collection. Courtesy Richard Green; © Patrick Heron Trust/DACS 2024

Nevertheless, this exhibition successfully presents Smith as a ‘master of colour’ (to cite Heron’s New Statesman article), alive to both its structural possibilities and contradictions. Moreover, bringing Smith’s work to Charleston allows viewers to appreciate his paintings alongside those of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, the artist’s Bloomsbury contemporaries, whose work hangs in the house next door. Smith’s painting Flowers (1925) – a one-time gift to Grant, part of the Charleston collection – is now displayed in the house studio, and blooms in a fresh context.

Still Life with Green Leaves (c. 1940), Matthew Smith. Courtesy Philip Mould & Company; © Estate of Matthew Smith

‘Matthew Smith: Through the eyes of Patrick Heron’ is at Charleston, Lewes, until 13 October.