From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1970, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrated the centenary of its founding, it held a ball comprising several events for the price of one. Four New York design firms decked out different sections of the museum in styles representing four distinct eras in its history: Arms and Armor became an 1870s ballroom, a Spanish Renaissance patio a belle époque party, the Egyptian courtyard a 1930s-themed nightclub and what was then a restaurant but is now a classical sculpture court brought proceedings up to date with a disco. Two thousand guests attended the benefit on 13 April and Garry Winogrand recorded the beau monde having a blast in photographs that could have been commissioned for a time capsule.

The Centennial Ball was not the main event in museological terms. In the 18 months the Met devoted to its anniversary in 1969–71, it also put on a series of symposiums, talks and concerts, screened a season of films selected by Henri Langlois (founder of the Cinémathèque Française), programmed five major exhibitions to highlight its collecting in very different fields (these included its first exhibition of contemporary art) and opened refurbished Ancient Near East and Egyptian galleries as well as an expanded Costume Institute – to pick some highlights.

The celebrations for the Met’s 150th anniversary couldn’t have been more subdued. In March 2020, just days after the unveiling of the new British Galleries and the opening of a Gerhard Richter retrospective, and a couple of weeks before ‘The Making of the Met: 1870–2020’ was to open, the museum closed all three sites (Fifth Avenue, the Cloisters and the Met Breuer) because of Covid. In a letter to department heads seen by the New York Times, the president and chief executive Daniel H. Weiss and director Max Hollein predicted a shortfall of $100m in revenue for the coming year and anticipated much lower attendance after the reopening, whenever that might be.

Over on this side of the pandemic, in June 2022 the Met announced a change at the top. After the retirement of Weiss the following year, Hollein would add the CEO role to his own and the museum would have a single leadership structure once again. Given his previous museum experience – two years as CEO and director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and as the head of three very different museums in Frankfurt before that – the news didn’t come as a surprise.

Speaking to Hollein last autumn, I asked him when the conversations about adding to his responsibilities as director began. When the trustees sounded him out about the director job is the answer, with Hollein sounding them out in turn: ‘Are you sure that you feel that I’m the right person because my strength – of course I come from a curatorial background – but I’m not the chief curator type.’ That curatorial background was also contemporary: after degrees in art history and business in his native Austria, Hollein worked in a variety of roles for Thomas Krens, director of the Guggenheim when it was planning several international outposts in the late ’90s. There is a strong family connection with the arts, too. Hollein is the son of Pritzker Prize-winning architect Hans Hollein; his sister is now director of the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna.

Unusually for the Met, when Hollein was appointed in 2018, he was the first director in 60 years not to have worked at the institution before, to come ‘totally from the outside. I’m not Met-bred.’ For a brief time then, the museum was led by two management-minded art historians – Weiss being a medievalist who also had an MBA – who saw eye to eye. Hollein says, ‘It was clear to both of us that […] this museum could also be run and operated in different ways. It depends very much on the people there and not so much on the boxes of a chart.’

As museums go, the Met is more complicated than most. Although it employs 900 fewer people now than when the financial crisis hit in 2008, its 1,700 members of staff still comprise one of the largest museum workforces in the world. Thomas Campbell, the Met’s tapestries curator who was appointed director in 2008 and resigned in 2017, describes the institution to me as ‘head-spinning in its complexity’, adding that what makes it work is ‘some of the finest curators and conservators and scientists in the world working with really top-notch administrative teams’, all under the eye of ‘one of the largest and most powerful museum boards in the world’.

Hollein seems to have been undaunted by the undertaking. Coming from the outside, he says, ‘in a certain way you learn, for sure, but then on the other hand, you need to act as well, because the history, the legacy, the belief in excellence, could also paralyse you’. There was plenty to get on with. As well as overseeing the completion of major infrastructure projects such as the European galleries, where some 1,400 skylights had to be replaced after decades of neglect, there was the challenge of raising the funds for a new modern and contemporary wing – a $600m project that had been put on hold in early 2017 after concerns about the museum’s operating deficit and shortly before Campbell announced his departure. Then there is the remaking of the galleries for African, Ancient American and Oceanic art in the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing (on course for completion in spring 2025). Also underway is the refurbishment of the Ancient Near East and Cypriot galleries (aiming for 2025 too).

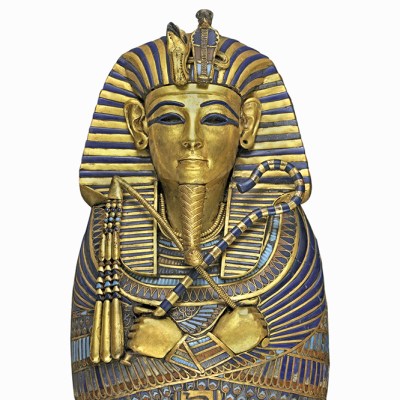

There have also been considerable unforeseen challenges too. Perhaps the most high-profile is that posed by the investigations of the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, whose Antiquities Trafficking Unit seized the gold coffin of the Egyptian priest Nedjemankh that had been acquired by the museum for $4m in 2017. The Met returned the coffin to Egypt after it was found to have been sold with a forged export licence claiming that it left the country before 1971 (the cut-off date for legal export); it was actually smuggled out during the Arab Spring. Formed in 2017 and led by Matthew Bogdanos, an assistant district attorney who likes busts to be public, the unit has made a string of high-profile seizures in New York (and even Cleveland). In September 2022, the Met returned 21 objects to Italy and six to Greece; March 2023 was another busy month for the museum: a headless bronze statue of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus – on loan from a Swiss collector since 2011 – went back to Turkey and 15 objects bought from the convicted trafficker Subhash Kapoor headed off to India. In this context, the reopening of the European Galleries: 1300–1800 at the end of the year may have come as a relief – a chance to change the conversation for a time.

The stream of headlines and commentary about the seizures and returns led to Hollein issuing ‘reflections’ on the subject of cultural property in May 2023. Identifying those parts of the collection that had been acquired from 1970–90 as being of particular concern, he announced the hiring of four researchers to concentrate on ‘several hundred or more objects’. The statement outlined other initiatives, but also asked for the museum to be allowed to implement them: ‘In some areas, we are able to make swift and definite moves, and in others it may literally take years to acquire the needed provenance information and even more time to collaborate with other museums, nations, or individuals to find the right solution.’

It remains to be seen how much time will be required – and if it will be too much for the museum’s critics. To oversimplify wildly, if museums in Europe have empire problems, the Met and other US museums have market problems. Like other US museums, since its founding the Met has relied on the largesse of its trustees and gifts from collectors who, in certain fields, cared very much for the quality of objects without caring to know much about how they came to be for sale. The museum has also bought directly from dealers and at auction too (and from dealers acting for them at auction). It is a cliché to say that attitudes have changed, but it’s also true that the change has been recent. The UNESCO Convention to combat the illegal trafficking of cultural properties dates from 1970, but it wasn’t until 2002 that the US dealer Frederick Schultz was convicted of trading in objects that had been smuggled out of Egypt. He hadn’t been involved in their removal, but the judgement set the precedent that laws concerning the cultural property of other countries could be enforced in the United States – and alerted museums and their trustees to clean up their act.

Anyone in charge of a department at the Met is looking after a collection that has been formed by the practices of predecessors with various attitudes and means of acquisition (those predecessors sometimes operating as differently from their contemporaries as from their successors). When referring to departments and the personalities who ran them, the terms that occur to some museum-watchers trying to explain how decentralised and, in some cases, politicking the Met could be include ‘the Holy Roman Empire’ and ‘The Vatican’. The generation of curators who turned a blind eye to questions of provenance has retired, but the institutions they worked at have to deal with the objects they were allowed to acquire.

There is some irony in the fact that for much of the Met’s history its directors spoke for a fissiparous institution in a way that wouldn’t wash now. Hollein is not the kind of director who shies away from the term ‘universal museum’, but stresses that ‘we are trying to be as multicentric as possible’. He describes demands for greater social justice after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 as ‘a kind of reckoning with museums’. Over the course of a generation, museums all around the world have become comfortable with speaking about ‘audiences’. In 2020, however, many institutions seemed very uncomfortable with how they related to their ‘communities’, if the latter was defined in a wider sense than museum members and the donor base. Addressing the situation isn’t a case of catering for different people, Hollein says, but stopping ‘pretending that the museum speaks with one voice […] let’s make sure we have this multiphonic orchestra of voices properly reflected in the institution, with all its discrepancies that come about, as well.’

It’s a point that Thomas Campbell, who succeeded the Met’s longest-serving director, Philippe de Montebello, makes in a slightly different way, as he explains his board-endorsed mission to expand the museum’s digital offerings when he took over: ‘Philippe was the spokesperson of the museum, the voice of the museum, overseeing a large production of catalogues […] but now we were in an age when multiple voices could be brought forward.’ The digital expansion would eventually become a source of tension, but in another example of an unforeseen event creating new circumstances (however unwelcome), it came into its own during the pandemic when screens were the only way to stay connected – with art, as with almost everything else.

Polyphonic effects can’t always be planned for. And not every controversial past acquisition has created a mess for the present-day Met. Last year, ‘Juan de Pareja: An Afro-Hispanic Painter in the Age of Velázquez’ had at its centre the Velázquez portrait the museum bought in 1970 for the then astonishing sum of $5.5m. In the excitable account of Thomas Hoving, who was a transformative director of the Met from 1967–77, there was no question that the museum must have an outstanding painting by the artist when it came on to the market, but the identity of the ‘Moorish’ sitter and his status as the painter’s slave then a freed man seemed to be of minor interest. As the subtitle of the exhibition in 2023 suggests, the show went to great lengths to put the painting in context and drew on the research of the pioneering historian Arturo Schomburg. In his memoir Making the Mummies Dance (1993), Hoving is determined to be outrageous, casually referring to smugglers he knows and undermining more conscientious figures, but a note of sincerity sounds every now and then, as when he writes that in the long run, the price of a great painting will be forgotten, but the picture won’t.

In another sign of changing times, the current exhibition devoted to the Harlem Renaissance (until 28 July) might be seen as a tacit apology for the infamous ‘Harlem on my Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968’ show of 1969. Although not intended by its external curator as an art exhibition, the emphasis in ‘Harlem on my Mind’ was on what its critics regarded as the ‘mere documentation’ of Black creativity. The exclusion of living artists such as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence – in the city’s most important art museum – was regarded by many as a mistake; a mistake compounded by the cavalier editing of a catalogue essay, which made a high-school essay quoting sociological research read as an endorsement rather than a description of anti-Semitism, and caused the catalogue to be withdrawn.

Returning to present controversies, if Bogdanos and the Manhattan DA’s Office seem laser-focused on the Met, it’s not just down to geography. Hollein describes the museum as ‘a very acquisition-driven institution, which is very different to peer institutions’ such as, say, the Prado or the Louvre. A glance at any recent annual report bears him out and this has been the case for decades. At times the Met also serves, Hollein says, as a cultural ambassador or minister for a country that has no culture ministry. Domestically, ‘it also means that you have a voice […] where you need to speak and act not only for your own institution, but for the whole museum field. I don’t mean this in any kind of aggrandising way, but it’s clear that once the Met decides on something it almost becomes policy for others.’

It’s a fine line for any institution to walk and a museum founded and sustained by private philanthropy will always run into changing notions of the public good – and whose money should be accepted along the way. As well as managing a huge staff and the expectations of the wider public, the director and CEO is also accountable to a board – another feat of management, though Hollein is too diplomatic to say so. Rather, as he puts it, ‘The Met is a construct of great philanthropy. It’s an institution that originated within a capitalist society: donors wanting to give back and being part of a society that lives on success; on the other hand, also making sure that’s shared with others.’

And what of those donors? A museum can spend decades courting a donor or hoping that a trustee will leave it their collection. Much of Hoving’s memoir is dedicated to his efforts to secure Robert Lehman’s outstanding collection of European paintings and decorative arts (‘What if he died before I could snag him?’). A major gift often comes with major strings – in the case of Lehman, the request (granted) that his collection be kept together in the museum (not dispersed as John Pierpoint Morgan’s was), in a setting that resembled his home, velvet wall coverings, rugs and all. There has been no such undertaking when it comes to Leonard Lauder’s transformative gift of 78 cubist paintings and sculptures in 2013 – but when the Met announced the gift (after years of discussions, one assumes; a donation is not made in a day) it made creating a new modern and contemporary wing that could display them more urgent. Of all the current projects, this is certainly a delayed one. In 2021, the Met announced that it had received $125m from Oscar L. Tang and Agnes Hsu Tang; the next year the Mexican architect Frida Escobedo was chosen to design the new wing, replacing David Chipperfield Architects, who had been attached to the project since 2015. In between Lauder’s gift and the present day, the Met has leased and let go the Breuer building as an interim home for modern and contemporary – and interdisciplinary – shows and the department has a new head.

Museums are very good at creating an illusion of permanence when, in fact, they are always in flux. Features that seem longstanding can be relatively recent (New Yorkers over 50 will remember a Met without those famous steps) and the name of a donor who has their name on a wall or a wing today may be mud the day after tomorrow. Nor would a Met director of an earlier generation have described the role as Hollein does: ‘You’re not just someone who’s just dancing around and drinking champagne; you’re someone who brings together communities in a thoughtful way and shows them respect […] to learn, to listen and sometimes course-correct in a meaningful way.’

It’s a rare visitor to the Met who can leave without feeling that no matter how many hours they have spent at the museum, they have seen so little of what there is to see. Even scores of repeat visits will put them on nodding terms with only a fraction of the 1.5m items in the collection. On an institutional level, to take in everything the Met is engaged in at any one time – and what the repercussions will be – is a hopeless task, not entirely unlike trying to see everything that is on display at the museum in a day. But regarding those efforts as a kind of time capsule, to be opened and examined at a later date, might help us see the present more clearly.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

13 March 2024: This piece has been updated to reflect the fact that the statue of Septimius Severus returned to Turkey had been on loan to the museum since 2011 and was not part of the permanent collection; and criticisms of ‘Harlem on My Mind’ in 1969 centred around the absence of art in the exhibition, not its subject matter.