In his book, The Family Silver, the photographer and writer Michael Collins has published a selection from the thousands of colour slides he has collected over three decades. He talks to Fatema Ahmed about looking through other people’s family albums and what these images might tell us about the medium of photography.

The book shows 42 pictures out of your collection of about 25,000 slides. Can you explain how the collection began and what you were looking for?

The book shows 42 pictures out of your collection of about 25,000 slides. Can you explain how the collection began and what you were looking for?

I’ve always been interested in family slides, partly because my father only took slides, up until we were in our teens, so all our family pictures – and there’s quite a lot of them – are slides. So they were for me the paradigm of family pictures. When I became more involved in photography, I realised that even though they were slightly naff and without any professional merit, they have an eloquence that goes to the core of what photography really is. The more I learned about photography, the more I valued this form of photography and I started collecting it, on Brick Lane, in junk shops – I’m talking about the early ’90s: pre-Internet, pre-eBay. People seemed to prize quirky ones – a plane sticking out of some unsuspecting person’s head in a garden or that sort of thing. Whereas for me they are devotional pictures and at their best they have a sincerity and eloquence to them that I really admire. Loads are of course in sharp sunlight and very shadowy, or they’re a bit forced, or the people are very uncomfortable. But when there is a harmony between the photographer and the subject and the setting, then the gods are really with you in terms of a portrait.

Is there any connection between your own photography and the kind of photographs you’ve been drawn to collecting?

I use a plate camera, I make very compositionally traditional pictures, landscapes among other things – I’m influenced by the matter-of-fact aesthetic of the record-picture photograph, which is exemplified in the work of, say, Bernd and Hilla Becher. That was then dubbed the Düsseldorf School, which is a very sober, clear, calm, unidiosyncratic compositional perspective. It can be cold, if you’re not careful. What I find mitigates against that chill is that it is the most faithful way of composing a picture – you’re not trying to make something look better or worse, or bigger or smaller, or threatening or benign; you’re just trying to make the most even-handed, clear photograph possible. Yet what came through to me in the Bechers’ work, particularly, is a sense of fascination for the subject, not least because they made hundreds of them. That metaphysical quality is evident in family slides, where you can actually see a sense of the dynamic between the photographer and the person in the picture.

Collection of Michael Collins

I’m struck by the phrase ‘devotional pictures’. Can you explain what you mean by that in terms of how the photographs were taken and also how they were seen?

The whole thing is quite cumbersome and wonderfully so. Taking the picture itself, you would almost certainly have to use a light meter, a separate piece of kit to the camera, initially. You were conscious of putting in a roll of 24 or 36 exposures. Most of the pictures I collected would be from the late 1950s and ’60s and some from the ’70s – beyond the early to mid ’70s the technology of cameras and film had advanced so much that you did have auto-focus and film speeds were faster. [The photographs] became sharper and they lost a certain cadence to the appearance of the film. But it would be a clunky ritual. You would have to wittingly participate, not just in taking the picture, but also in viewing it and that has what you might call these days a slowness – certainly it is a different form of attention. Why is it, for example, that people believe it takes longer to look at a painting than a photograph? I don’t get that, because a lot of paintings aren’t worth looking at for very long, ditto so many photographs. And, let’s face it, you darken a living room and put up a screen and then turn on a projector and smell dust burning on the bulb, that’s an incredibly evocative situation.

In the introduction to the book you give the examples of Nadar and Jimmy Forsyth – who are not usually mentioned in the same breath – as portrait photographers who got something special out of the people who posed for them. Can you say a bit more about the importance of the relationship between the photographer and their subject?

If you take a picture of a stranger, it’s going to be a picture of a stranger. Photography is so subtle in how it works; it picks up on those things. I’m forever saying to people who commission family portraits, why on earth would you commission a stranger to take a picture of your children? You should be doing it yourself. It makes no sense to me and they obviously think I’m some sort of crank – but I’m right. The way the child will respond to them will be far more meaningful than the way it would to someone wearing a comedy bowtie.

Collection of Michael Collins

Someone who knows the people and the places depicted in the pictures in this book is going to have a very different view from what the rest of us will see. What guided your selection of slides – how do you respond to them and how do you want others to respond?

One of the great things about photography is that, unlike prose, the photograph never actually says anything, either to confirm or deny your assumptions. It means that you interpret that picture based on your life experience and your perceptions. I’ve yet to hear back from anybody who knows the subjects of the pictures, but those who do will have a much more informed engagement with the portraits, because they will bring a backstory, which, even if it’s in captions, we don’t have.

I met Jimmy Forsyth a couple of times, and once before he died he went through his albums with me and was talking about some of the kids’ lives as they grew up and it was a bit grim […] and I thought, ‘Oh, Jimmy, I don’t want to hear this.’ You could say that’s a sentimentalised way of wanting to contextualise the pictures. I don’t think so, because I’m not looking at those pictures as part of a life continuum but as portraits made then and there in their lives, as with these pictures here.

Do you know anything about the people in these pictures?

I do have caption information on some of the slides. Sometimes I would buy a big batch of slides on eBay and that would include dozens of rolls of film in slide format, from one family’s life, and you could see them get older. It was quite strange, [seeing them] changing from little kids to university graduates. But I wanted to withhold any information, so that you’re left entirely to your own devices when you look at them.

Collection of Michael Collins

What kind of decisions do you think the takers of these photographs were making? Is it an accident, for example, that quite a few of these pictures look like view postcards or paintings, or remind me of John Hinde?

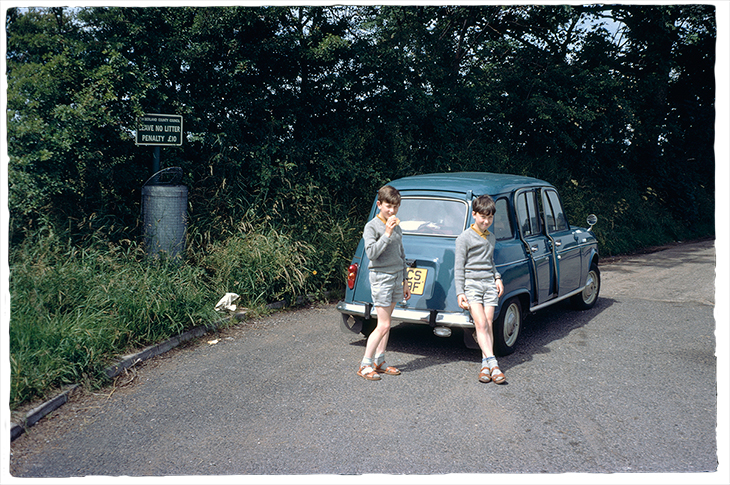

The ones that remind you of John Hinde are because they remind me of John Hinde! I wanted to begin and end with motoring scenes because when I think back about childhood and photography, I can never remember a single actual act of being photographed, but for some reason I tend to associate them with day trips in the car, either going to a National Trust place or to the seaside. I felt it was a way of symbolically taking you into the family’s world and also highlighting the fact that possessions had much more personal meaning than they do now. Cars are anonymous, nasty, shiny things now; they weren’t then. But the opening picture in particular has that John Hinde composition about it.

You’ve mentioned that people took fewer photographs, which explains the sense of occasion in these slides: people are dressed up, they seem to be on an outing or in a new uniform. But, I wonder, why are there so many photos of cats?

I don’t know whether you know those books by Libby Hall? She did this original book called Prince and Other Dogs and they’re reproductions of cartes des visites of dogs, and also owners and their dogs. It’s one of my top 10 photo books. What’s great about it is that when someone’s there holding their dog or sat with their dog, or holding their cat, they are emotionally far more open and softer than if they were holding a telescope or a walking stick or a football. In quite a lot of family pictures, people will be photographed with their dogs, but of course cats and dogs being what they are, often the head will be blurred or the person will be grabbing them like Mark Field, trying to get them to sit still in the picture, so it looks nasty. But when it does come off, I really like it.

Collection of Michael Collins

The picture of the cat on the bonnet of the Morris Minor, I love for various reasons. (Not least my mother’s father had a car exactly like that.) I love the idea that someone saw the cat – on the slide mount he’s called Smut, because of the black smudge on his face. I love the idea that someone who would only have taken 20 or 30 photographs in that year took one of Smut on the warm bonnet of the glistening Morris Minor. It’s such a perfect composition – the distance. One of the riddles in photography is: are you too close or too far? It’s very easy to get it wrong and it’s just perfect how they’ve done it. Like the picture of the lupins – it’s perfect and it’s so perfect I couldn’t tell you why; it just is.

You mention the perfect pictures, but you’ve also chosen to include quite a few imperfect ones.

If you notice the two ladies standing in front of the big bank of flowers, it’s slightly soft, but so what? There’s just such a fantastic calm and charge to it, it’s a terrific picture. And the woman in the garden with her daughter is slightly soft, but so what? She looks lovely in that dress. There’s a terrific sense of harmony and it’s not an advert harmony.

Collection of Michael Collins

There’s a wonderful sense of both ease and formality about the couple on the front cover – there’s almost a touch of Gainsborough about them. Can you explain why they appealed to you?

There is a [bit of] Gainsborough, you’re absolutely right. In fact that family, there are three pictures [in the book]: there’s the lady sat in the chair with the mirror behind her, a kind of Van Eyck, and they’re sat on some rocks with their dog in a preceding picture. But that Gainsborough composition is wonderful and as to who took it, I don’t know, but it’s so very English.

Did you think at all about what it was to represent Englishness and to represent it like this?

I thought, I’m going to get some stick here for it being so white and so broadly middle class and southern… Yet that’s where I came from, so on the one hand, I picked the pictures that are the most evocative to me but, also, these were representative of what I found. I wasn’t looking in junk shops in Birmingham or Bradford or Manchester; I was looking in London and Dorset, which is not a great sample, let’s face it.

The collection for me became extremely autobiographical. The picture of the boy wearing a red blazer with his bicycle and the ginger cat is so like me at that time, at that age. It was very much unconsciously and consciously looking back at a life that was gone. So it became extremely evocative to collect those pictures and I became more and more self-referential in my terms of assessing them.

Do you have plans to make an exhibition of them?

If you make prints, they tend to be shiny, which is not really what the things are. If you make little Jeff Walls, that’s just not what they are, either. I scanned one – the one on the cover – to the size of about 21 by 14 centimetres, and put it on the same film material as the slide itself. I set that on an LED panel and put that in a much larger window mount – as for example the British Museum would exhibit a drawing by Raphael, or something like that. So you have a huge mount with a small picture in the middle of it, without a frame. And it looks unbelievably beautiful. I’m determined to do something with them.

The Family Silver by Michael Collins is published by Lecturis.