There was, as she intended, a combative note in Minnette de Silva’s idiosyncratic scrapbook of an autobiography, The Life and Work of an Asian Woman Architect. It took the last ten years of her life, and emphasised her role as a nerveless pioneer and professional, instigator of what became known as ‘regional modernism’. Yet for all this, she has been almost wholly overshadowed by the (literally and figuratively) towering figure of Geoffrey Bawa – her contemporary, but a latecomer to architecture. In 1998, as the collaged version of her life was being readied for publication, she died, isolated and almost forgotten.

In 1987, de Silva took the stage at the 16th conference of the Union Internationale des Architectes (UIA) held in Brighton. I wrote about her work in the Financial Times then, about her aspirations towards a ‘workable synthesis of traditional and modern architecture’, and triggered a sustained campaign by de Silva herself, and her Cambridge-based sister Anil, to persuade me to contribute to the book she was planning. Never having visited Sri Lanka or seen her work for myself I was reluctant, but capitulated in the face of their insistence.

I had sensed in her presentation something particular, a credible fusion of modernity and the vernacular. In January, I finally visited Kandy, where the shreds of evidence were before me, in the first and last of her commissions in her home town.

De Silva was born in 1918 to enlightened, activist parents (‘their life could be a metaphor for what Sri Lanka should be’), who nevertheless discouraged her from taking up architecture as a profession. Persistent to her toes, she lost no time in becoming the first woman architect in Ceylon, embarking on training and practice in Bombay and, with her equally able sister, in 1945 instigating a progressive arts magazine, MARG (the Modern Architectural Research Group), with its editorial board made up of key figures across the arts in both India and Ceylon. She travelled widely and spent two years at the Architectural Association in London (she figured in ‘AA Women and Architecture 1917–2017’, the recent book and exhibition marking the centenary of women’s admission to the AA). In 1947, as the MARG delegate, she was photographed in the front row of the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) meeting in Bridgwater, Somerset, eye-catchingly sari-clad, with Walter Gropius at her side and Le Corbusier, whom she had first met in 1945, on the far left. For a student in her twenties, she had made a considerable mark in the world of international modernism.

The dining room of the Karunaratne House, looking up to the study at intermediate level (photo: early 1950s)

De Silva returned to Ceylon in 1948 with a domestic commission secured. The clients were Algy and Letty Karunaratne, conservative Buddhist friends of her parents; the site high above Kandy Lake in the wooded hills. Unlike almost all of her early commissions in the town, the house still stands, awaiting its fate in the hands of unidentified owners. Even with the attrition of much of its detail, it demonstrates her grasp of the essentials of the site and the exigencies of the climate, with the almost entirely solid south (entrance) elevation, and the north side’s glazing and balconies shaded by deep eaves overlooking the garden and the views beyond. Inside, the free flow and interconnection of spaces and levels was dictated by a lazy, curved stair: living (and parties) was upstairs, sleeping and eating downstairs. If the surviving materials speak of late-period modernism – concrete, rough boulder stone and glass bricks – the finishes were a celebration of tradition and local craft.

In 1953, MARG devoted 11 fully illustrated pages to the house. David Robson, the leading authority on the work of both Bawa and de Silva, notes that ‘it read like a manifesto for a “Modern Regional Architecture” and was very influential.’ But for all her seeming confidence, in her book de Silva revealed how unnerving the construction process had been. Before work began, a posse of monks (photographed crouching under umbrellas) blessed the project, but as the walls rose the clients became increasingly worried by growing costs and their choice of a novice architect and, above all, ashamed by the notoriety their disconcertingly modern house was attracting. With her customary forthrightness, de Silva told them it was a ‘research work in progress’.

The interior of the Karunaratne House in January 2018, looking down into the former dining room Photo: the author

With the introduction of traditional finishes – Dumbara-woven curtains and mats hung as door panels, black-, red-, and gold-lacquered wood balusters and satinwood parquet floors – they began to warm to it. Later letters from client to architect are effusive, full of rapture at the way she had caught and mediated the light and the views, and how the flow from room to room and level to level gave the house such rhythm and consonance – which, even in its tragic current state, it still conveys. Their granddaughter remembers wonderful times in the house as a small child, memories coloured by the Le Corbusier palette of earth red, cerulean blue and cool green (the latter in the bedroom in which she recovered from chickenpox).

In the 15 years after her return from London, de Silva built a series of private houses, mostly in Kandy but some in Colombo, but also social and cooperative housing, reflecting her father’s role as minister of health. Now only the first, derelict, house and her final commission (from the 1980s) survive in anything like their original form. Most have been demolished due to the value of their sites.

In the late 1980s, Lynne Walker, the feminist architectural historian, was working at the RIBA when de Silva appeared unannounced in her office. Far from the sad, disillusioned figure sometimes pictured, Walker met an ‘electrifying’ person, ‘dynamic and beautifully turned out […] She was networking, making sure that she was included in any publications or events about women in architecture.’ Ten years earlier de Silva had written regional entries for the revised edition of Banister Fletcher’s History of Architecture, observing that ‘Ceylon, like the whole of the East, is striving to synthesize European and American ideas and technology with indigenous ways of living and traditional expressions.’

The auditorium, or ‘audience hall’ of the Kandy Arts Centre, in January 2018 Photo: the author

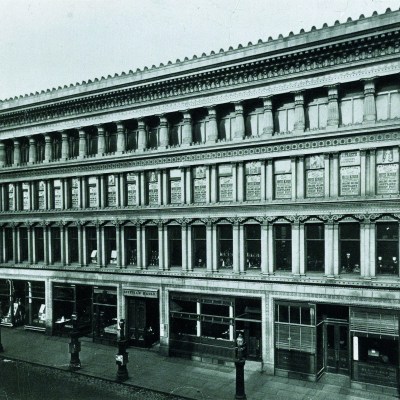

With the commission for the Kandy Arts Centre in the 1980s came de Silva’s most ambitious effort to integrate the two. Her final work stands on the edge of the lake, close to the famous Temple of the Tooth, and revolves around an immense two-tiered ‘audience hall’, partly open sided in Kandyan palace tradition, seating up to 1,000. It was built to mark the centenary of the city’s art association, and to celebrate and nurture local crafts, but the identity of its ‘internationally recognized’ architect is confined to a little notice under large framed portraits of local luminaries, pointing out that she was ‘the daughter of former state councillor for Kandy George E de Silva and the sister of former MP, Mayor and Ambassador Fred E de Silva.’ Even in the 1980s Minnette de Silva’s achievement was limited by her status, as Robson puts it, ‘in what was still a man’s profession within a chauvinist society […] in a provincial backwater’. Substantially altered, its roof sweeping over an intricate timber structure, the Kandy Arts Centre remains a cultural building of which any town might be proud, by an architect of whom Kandy could and should be prouder.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.