From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I meet Miquel Barceló in the sterile surroundings of a hotel foyer in December, in the far south-east corner of Spain. On an empty mezzanine we sit hunched over a low coffee table. It is about as unsympathetic a context in which to interview an artist tired from travel as one can imagine. But Barceló, brown-haired, puckish, his expression a mixture of boyish mischief and wearied kindness, is full of excitement. We are in Almería, a city notable for its spectacular Arab fortress, the Alcazaba of Almería, and the bare rugged mountains popular with directors of spaghetti westerns. Barceló has arrived for the opening at the Museo de Almería of ‘Reflections: Picasso x Barceló’, an exhibition of more than 100 ceramic sculptures by him and by Picasso, shown alongside archaeological objects from the museum’s collection. The show is the second in a series, organised by Museo Picasso Málaga, that pairs the modern Spanish heavyweight with a contemporary artist – Jeff Koons was given the latter spot in the first instalment a year ago, at the Alhambra in Granada. The collection of the Museo de Almería, founded in 1933, spans more than 5,000 years, with many local finds dating back to the Neolithic period. As a specialist archaeological museum, it was considered the appropriate venue for the first leg of this exhibition, which travels to the Museo de Cádiz in March.

Born in Felanitx, Mallorca, in 1957, Barceló first garnered attention in his early twenties, when he participated in the 1981 São Paulo Art Biennial and, the following year, at Documenta 7 in Kassel. There, with fellow exhibitors including Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, he showed the ambitious Nu pujant escales (‘Male nude ascending a staircase’, 1981), inverting Duchamp. In subsequent years, Barceló shared Basquiat and Haring’s dealers, Leo Castelli and Bruno Bischofberger respectively (today he is represented by Thaddaeus Ropac). His oeuvre encompasses highly textured multimedia paintings, vigorous woodcuts, ethereal watercolours, exuberant bronze sculptures and expressive ceramics, alive with the energy of metamorphosis. He acknowledges inspirations as wide-ranging as Velázquez, Jackson Pollock, Joseph Beuys and Cy Twombly. But a fundamental passion is the prehistoric cave painters of Chauvet, Lascaux and Altamira. ‘I feel so close to the artist in Chauvet,’ he has said, ‘that he [could] be my brother.’ Barceló is part of the multidisciplinary scientific team responsible for studying and preserving the 36,000-year-old cave site in the Ardèche, France; it is as if he has an unassuageable hunger to be in at the beginning.

The morning of the day we meet, Barceló has been given free run of the store beneath the museum. In the kind of performance that has become an aspect of Barceló’s radical art-making, the artist has created from his gleanings, in one corner of the exhibition space, a Christmas nativity scene. While garish plastic virgins, saints and shepherds smile wanly in Almería’s shops, Barceló has chosen archaic fragments of unglazed clay, roughly shaped into animal or human form, from across the layers of civilisation represented in the museum, and placed them alongside small pieces by Picasso and by himself. They are, as he explains, ‘the things we never show, like the broken things or fragments, the things not ready for exhibition, things that are not even titled, that galleries would not take, that are not for the market – you know, marginalia’. To one side a clay cave-like structure serves as the traditional stable, with a voluptuous reclining nude presiding, serenaded by an almost two-dimensional flute player – both by Picasso – overlooked by Barceló’s ass’s head. Stretching out to the other side is a loose procession of clay bulls, clay shells and surreal shell-like ears, birds, horsemen and humans. All the pieces are different scales, and hold together not so much as an act of representation, but in honouring the moment of actual creation, the idea born in the hand as a human being models clay. Barceló tells me: ‘You can see a little bull from the Palaeolithic period, made with just three fingers – like that, like that, like that – and you can even find the mark of the finger, the prints of the artist. And you can see another bull by Picasso, who probably never saw this particular bull from Iberia, but it is very similar. And you see my bull. I too make it just like that and it’s the same spirit and the same clay, very close from one to the other, made within some hundred kilometres [of each other]. And yet there are 6,000 years between these works.’

Since leaving school, Barceló has operated as if untethered by time or space. He explains that having been born in a village on an island, he felt a strong urge to find new horizons. As Franco lay dying in 1975, Barceló spent one week at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Barcelona before returning to join the 1976 happenings of Taller Llunàtic, an avant-garde conceptual group in Mallorca. The ‘heavy piece of marble’ which had weighed on the heads of artists 10 years older than him had been lifted. Barceló secured a diagnosis of ‘psychopath, schizoid, the worst’, which excused him from military service, the usual route to a passport. With the pretext of seeking treatment in Switzerland, he took his documents and vanished into the museums and galleries of Europe and beyond, train-hopping, sleeping wherever, and finally landing in an empty church next to the Institut Curie hospital in Paris, giving him 10,000 sqm in which to paint.

Barceló had been painting since childhood, encouraged by his mother, a painter of traditional Mallorcan landscapes. For his first gallery exhibition in 1974, at the Galería d’Art Picarol in Mallorca, he produced drawings of insects and molluscs, digging deep into the natural world of the island – sea, land and sky – which has sustained his imagination ever since. And it was as a painter that he first made his name. But through his encounters with German artists such as Anselm Kiefer and Sigmar Polke, Italy’s Arte Povera figures, the art informel of Dubuffet et al., and other art movements across Europe and the United States, he began to develop a diverse practice unfettered by distinctions between materials, genres and forms. ‘Often I had this feeling,’ he says, ‘that paintings and sculptures are, for me, absolutely the same. Painting and sculpture, it’s like abstract and figurative. It’s all just the metaphysic of the 20th century. For me, art is like it was 7,000 years ago. All one.’

In Mali in the late 1980s, with the Harmattan wind shredding his papers and canvases, he found in clay a new way to reclaim that ancient ground. ‘In the Dogon, the potters are women. So three generations of women were my teachers. They taught me to collect the clay, to prepare the clay – it was longer to prepare the clay than to make a sculpture – how to fix the cracks, how to use the manganese.’ At first he was shocked when the portrait heads he made shrank as they dried. He created one skull with a large ear, ‘because the Dogon always say the dead listen’; then one ‘with a long nose like Pinocchio’. For Barceló as for Picasso, clay became an arena for serious play.

It has evolved into an increasingly important strand of Barceló’s work, in parallel with his painting. In Mallorca he has two studios, one for each activity. The exhibition in Almería reconstructs the shelf of vigorously modelled ceramic heads that greets visitors to his ceramics workshop. He values clay’s durability and sensitivity: ‘Because the clay has this memory like the flesh. You just touch it and the mark is kept. It is also very fragile but long lasting. It is a perfect paradox.’ Or, as he says in the exhibition catalogue, which features a conversation with his old friend Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Picasso’s grandson (who suggested the show): ‘It allows me to advance. Ceramics are a multiplicity, a tool, a delirium.’

Nowhere is this clearer than in the Chapel of Saint Peter in the Cathedral of Palma, where between 2001 and 2006 Barceló created a mural installation. The entire chapel wall has become a magnificent fever dream, dramatising the story of the loaves and fishes: fish with gaping mouths emerge wriggling from the sea of clay to the left, while loaves and wine jars apparently replicate on the right. In the middle a haunting pale figure of the risen Christ seems barely to burst through the clay. Barceló sees this work as a conversation with the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, whose own abandoned project here he greatly admires.

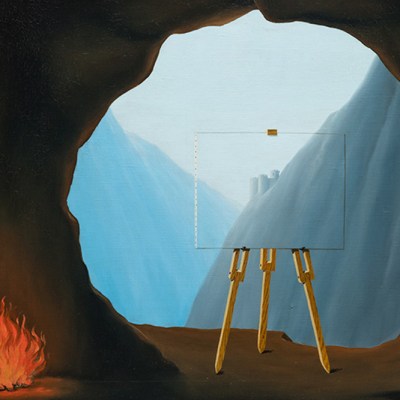

But if Barceló is drawn to the earth, he is also of the air. In the Museo de Almería, the cave is as Platonic as it is Judeo-Christian – the creatures like shadow puppets on the wall of the gallery. Ideas matter to him as much as materials. For another fundamental source of inspiration for Barceló is literature. He learned to read at the age of three, to the astonishment of his mother and the local librarian, under whose eye he read avidly for four to five hours every day throughout his childhood. His mother wept over the fact that he had read Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, a book he has subsequently illustrated, by the age of 14. As he explains, ‘For a boy to read Kafka, it is like you have lost your virginity or something. You know the dark side of everything.’ The thickly impastoed painting L’Amour Fou (1984) shows a luxuriously reclining male nude with erect penis, in a room lined and carpeted with books, with a giant window overlooking the swirling sea around a Mallorcan cove. The books’ own materiality seems to offer a domain as compelling as the world on to which it offers a window. Indeed as early as 1980, Barceló had worked directly with books, drawing on them in vinyl and pigment, pieces that he would later display at the 1981 São Paulo Art Biennial and which were recently included in the exhibition ‘Miquel Barceló: Autofictions’ at the Jan Michalski Foundation in Switzerland. And as suggested by ‘Miquel Barceló and the Written Worlds’, an exhibition currently running at the DOX Centre for Contemporary Art in Prague, the world of books and above all poetry may be the closest to reality. ‘Poetry is for me closer than painting,’ he says. ‘For me it is the closest, more than cinema, more than photography. The rest is technique and material. The idea of how the world became image is in poetry, as it is in painting.’

This excitement – about idea becoming image – is always present in Barceló’s work, most purely and abstractly perhaps in his 2008 project for the Human Rights and Alliance of Civilisations Room of the United Nations Office in Geneva: a ceiling of multicoloured stalactites formed from pigment, like the roof of a cave. As he also points out, the woodcut portraits of writers from 2015 on show in Prague, which include Anna Akhmatova, Leo Tolstoy, Gérard de Nerval and Isaac Babel, are called xylografies – ‘wood writing’ – in Catalan, a dialect of which is spoken in Mallorca. Barceló has had no ambitions to be a writer, however. ‘I am a painter. It is obvious! But I am a good reader and it is not easy to be a good reader.’ The range and breadth of his reading is evident in his work: from the early canvases Virgil and Hamlet, on view in Prague, to his humorous ceramic portraits of Kant, Deleuze, Plato and Wittgenstein from 2017 to more recent paintings of churning seas with what might be small white boats, buffeted and capsizing, tagged Poe, Nerval, Yeats or Tsvetaeva.

The exhibition in Prague also features series of watercolours from the three large book projects he has undertaken: The Metamorphosis, in 2019, the drawings viscerally evoking Gregor Samsa’s predicament; Goethe’s Faust in 2017, with its fantastical creatures born from streaks and blots of paint; and the most substantial of all, with more than 300 delicate, dreamlike watercolour drawings illustrating Dante’s Divine Comedy, which Barceló exhibited at the Louvre in 2004. As the Prague show’s curator, the writer Enrique Juncosa, suggests in his essay for the catalogue: ‘In none of these three cases is it a question of drawing literal images, but rather of creating parallel universes.’ A way of doing that, of translating the spacious, fluid, vivid experience of reading into drawing, Barceló honed through his Dante project: ‘When I decided to do Dante, I knew only the Hell. Not Paradise or Purgatory. I then read them and of course they are so visual and so plastic.’ His hope, as we enter 2026, is that his experience with that will support his current proposal to create a major ceramic installation for Gaudí’s great unfinished monument in Barcelona, the Sagrada Família – translating Paradise into clay. Meanwhile, three tapestries designed by Barceló are currently being woven for installation at Notre-Dame in Paris. For an artist who hit his stride in an abandoned church in the French capital, it must feel something like the completion of a circle.

‘Miquel Barceló: Reflections. Picasso x Barceló’ is at the Museo de Almería until 15 March, and at the Museo de Cádiz from 26 March–28 June.

‘Miquel Barceló and the Written Worlds’ is at the DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague, until 8 March.