From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1894 Edmund Gosse wrote a series of four articles in Art Journal hailing ‘The New Sculpture’. Pointing to Frederic, Lord Leighton’s An Athlete Wrestling with a Python of 1877, the work of his intimate friend William Hamo Thornycroft and bronzes by Alfred Gilbert, George Frampton and others, he noted a ‘wholly new force’, ‘startling and revolutionary’ and above all more ‘vital and nervous’ than the neoclassicism then prevalent in British sculpture. Since then, British sculpture has seen further pivotal moments – including Jacob Epstein’s models of 1907–08 for 18 stone sculptures adorning the former British Medical Association building on the Strand, and Henry Moore’s turn to free carving in the early 1920s.

In fact, there is a case for tracing an invigorated, dynamic tradition in modern British sculpture back two decades before Gosse (Susan Beattie made it in 1983 in her book The New Sculpture). The 1870s saw an influx of ideas from Europe. The great realist French sculptor Aimé-Jules Dalou, Rodin’s friend and rival, exiled to England for his role in the Paris Commune, taught modelling at the South Kensington School of Art and then at the Lambeth School of Art. His pupil Alfred Drury blended Dalou’s influence with reverence for the ‘English Michelangelo’, Alfred Stevens. Gilbert, meanwhile, travelled to Paris and Italy: his first statue in bronze, Perseus Arming (1882), inspired by a visit to Florence and cast in Rome, reflected the influence of Donatello and Cellini. Perseus Arming was influential not just for its graceful aesthetic but also for its method, cast using the Renaissance lost-wax technique, largely abandoned in France and Britain in favour of piece-mould sand-casting. During the 1880s and ’90s, while some artists – Gilbert and Thornycroft among them – experimented with casting their own work, new foundries opened in Britain and a wave of Italian founders arrived, fostering a distinctive tradition of British bronze sculpture.

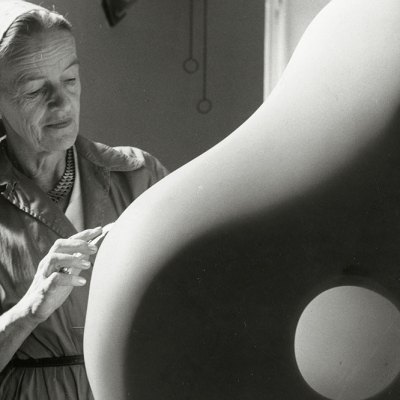

Into this settled world of idealised realism burst the émigrés Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska with powerful, abstracted sculptures, influenced by African, Indian and Assyrian collections in the British Museum, and by the modernism of Brâncuşi. Ezra Pound acclaimed the new British sculptural avant-garde in an essay of 1914 called, like Gosse’s, ‘The New Sculpture’. In the 1920s, the experiments of Moore, John Skeaping and Barbara Hepworth with free carving furthered the evolution of a distinctively British modernist sculpture. Hepworth learned to carve in Rome, where she met Skeaping, who became her first husband. Gradually, naturalistic forms gave way to more abstract sculptures. Meanwhile, for Moore, direct carving – as opposed to carving by a craftsman working from a model – expressed a vision of the sculptor’s craft that emphasised the human hand and a responsiveness to materials. It was not until after the Second World War that he was able to work on a large scale with bronze. His Reclining Figure: Festival, made for the Festival of Britain in 1951, marked the first time, he said, ‘in which I succeeded in making form and space sculpturally inseparable’.

For the first wave of new sculptors, Robert Bowman of Bowman Sculpture reports that the ‘market has remained solid and consistent with rises appropriate with inflation in general’. Less celebrated members of the school, such as Henry Fehr or Francis Derwent Wood, have a steady audience, ‘but the biggest movers price-wise have been the classic images: Leighton’s Athlete Wrestling with a Python and The Sluggard, Gilbert’s St George, Perseus and Comedy and Tragedy. All are in great demand.’ This is confirmed by dealer Willoughby Gerrish: ‘American institutions recognise that these are modern British objects – not merely the end of the long 19th century.’ He cites Thornycroft’s elegant contrapposto figure The Mower (modelled 1884; cast before 1925), bought from Bowman Sculpture by the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut in 2022. This year at TEFAF the Art Institute of Chicago purchased an 1899 cast of Gilbert’s St George, originally commissioned as part of his lavish tomb for the Duke of Clarence at Windsor Castle. A double-sized version, privately commissioned from the sculptor in 1895–96 – an example of the breach of Royal exclusivity that dogged and frustrated Gilbert’s later career – sold for £1.2m at Bonhams London in December 2020.

In 2013 Christie’s sold a posthumous cast of Leighton’s Athlete for £493,875. According to Scarlett Walsh of Christie’s, that year represented an earlier peak in this market. In July 2021, Sotheby’s sold a smaller, life-time cast of Leighton’s groundbreaking, languid The Sluggard (1886/1890) for £44,100, against a high estimate of £30,000. In the same sale, a large cast of Gilbert’s Perseus Arming, from 1911, went to a private collector for £52,920 (mid estimate). Christopher Mason, head of European Sculpture & Works of Art at Sotheby’s London, notes that, in addition to these well-known sculptures, ‘unique and rare objects sell very well’. He cites a monumental white marble bust of Queen Victoria carved by Gilbert, dated 1887–89, saved from export and sold to the Fitzwilliam in 2018 for £1.1m. Beyond the star names, Willoughby Gerrish’s recent show ‘Alfred Drury and the New Sculpture Movement’ coincided with a substantial £21,760 achieved at Bonhams London on 1 July for Drury’s crouched, swirling female allegorical figure representing the arts.

As Matthew Bradbury of Osborne Samuel Gallery notes, if Gaudier-Brzeska bronzes ever came to market they would be highly sought after – at Frieze Masters the gallery will show Gaudier-Brzeska drawings around a loan from Kettle’s Yard of his extraordinary plaster Bird Swallowing a Fish (1914). Epstein’s early work is also prized. ‘Prices for Epstein’s later commissioned portraits, however, have hardly developed unless you are looking at a portrait bust of Winston Churchill.’ The market for Eric Gill, on the other hand, has been sunk by revelations about his personal life. The gallery specialises in Henry Moore’s rare early carvings. Bradbury sold a haunting alabaster mask from 1929 when at Bonhams in 2018. Estimated at £1m–£1.5m, it was being offered for sale for the first time for more than 80 years and made £3.2m. Last year at Frieze Masters, the gallery sold an ‘exquisite’ ironstone carved head from 1930 to a new collector for a seven-figure sum. They also have a few early bronzes by Moore worth between £40,000 and £250,000, depending upon size, rarity, edition number and condition.

Bradbury notes a rise too in the market for Hepworth sculptures in recent years. At one time the later monumental bronzes were most competed for, but today, according to Alice Murray, Modern British and Irish Art specialist at Christie’s, collectors seek out her ‘unique, handcarved earlier pieces’. As with Moore, ‘collectors are drawn to the unique object and the hand craftsmanship.’ This interest in craftsmanship has led to high prices also for lesser-known contemporaries such as Ronald Moody, recently the subject of a major exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield. His Crouched Male Figure (1950–52), carved from oak, fetched £40,320, four times the top estimate, at Christie’s London in March 2024. Currently, however, Tamsin Golding Yee, specialist in Modern British and Irish Art at Sotheby’s, notes that the most popular period is ‘the height of early modernism – late 1920s, early 1930s’, when Moore, Hepworth and Ben Nicholson were all in London. An otherworldly white alabaster head by Moore from 1929, given to Nicholson in 1931, sold at Sotheby’s London in November 2023 for £4.5m, well over the £3m top estimate. But other artists do well: a sandstone Female Torso by Frank Dobson (1926) sold in a cross-category sale in March 2021 for a startling £2m, almost six times the upper estimate.

From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.