‘This market is all about exciting clients with something that they have not been exposed to before,’ says Alex Rotter, formerly of Sotheby’s and now chairman of post-war and contemporary art for Christie’s Americas. One of the things that excited buyers in recent years were the calligraphic ‘blackboard’ paintings of Cy Twombly. In 2014, one sold for a record $69.9m; the following year, another took pole position when it fetched $70.5m. Last May, a third changed hands for $36.7m, slightly less than the estimate. It was time for something else. Leda and the Swan of 1962, a painting that has never before appeared at auction – or even been seen in public for nearly three decades – and one of two large-scale paintings on the theme: the other is in MoMA. The 17 May New York sale follows hard on the heels of the US artist’s retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. ‘The timing is good,’ Rotter says. ‘The market seems very resilient and responsive.’

Leda and the Swan (1962), Cy Twombly. Sotheby’s New York, estimate: $35–$55m

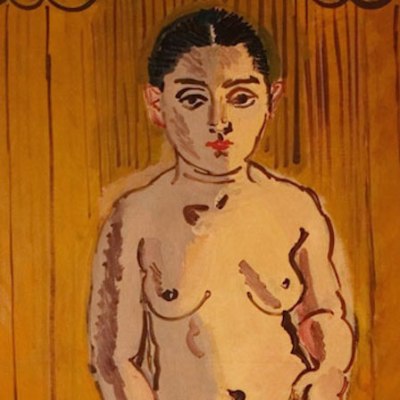

Twombly first visited Italy with Robert Rauschenberg in 1952, and was profoundly struck by life lived against the backdrop of history – and by the graffiti scrawled or scratched on to distressed and ancient surfaces. Settling in Rome five years later, he immersed himself in classical mythology – seemingly drawn to tales of sensuality, eroticism and violence. In this mythological encounter, much favoured by artists, the god Zeus took the form of a swan in order to ravish the beautiful Leda. While the MoMA canvas, with its prominent hearts and phalluses, proposes the moment of love and lust, this more tumultuous and visceral interpretation, with its suggestion of blood and scratch marks and great gobs and spatters of impasted pigment, seems to focus on the thrashing and brutality of the rape itself. It is a vortex of oil paint, lead pencil, and wax crayon.

While the calligraphic blackboard paintings of the 1960s are essentially conceptual, these earlier, more painterly canvases take their place more comfortably within the traditional canon of Western art, and may well also appeal to collectors of Abstract Expressionism. The painting’s estimate of $35m–$55m seems conservative based on the recent private sale of a painting from Twombly’s Ferragosto series of the same period for a reputed $60m–$70m.

Tempestuous couplings loom large in the work of Francis Bacon. Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary sale also features the artist’s first portrait of his great muse, George Dyer, a triptych of three small, separate canvases completed within three months of their fateful meeting in 1963. The pigment is visceral here, too, and in the smeary, stretched and mobile planes of Dyer’s face that also seem to incorporate the artist’s own features, it seems as if Bacon is painting them both melded in the throes of passion. Like the Twombly, this is also the work’s first auction outing, although the triptych has been much exhibited. It will only add to its allure that this was also one of several works by Bacon once owned by the writer Roald Dahl, a close friend of the artist. Estimate $50m–$70m.

According to the auction house’s Loic Gouzer: ‘George Dyer is to Bacon what Dora Maar was to Picasso. He is arguably the most important model of the second half of the 20th century, because Dyer’s persona as well as his physical traits acted as a catalyst for Bacon’s pictorial breakthroughs.’ It is quite a coincidence that Christie’s New York is this season also offering a Picasso portrait of Dora Maar in its 15 May sale.

Femme assise, robe bleue (1939), Pablo Picasso. Christie’s New York, estimate: $35–$50m

Femme assise, robe bleue was painted on Picasso’s birthday in 1939, just months after he first met Maar and soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. At the time, he was still involved with the soft and sweet natured Marie-Thérèse Walter, and the complex, intellectual Surrealist artist and photographer Dora Maar could not have proved a greater contrast. He captures a sense of her tension – and perhaps the anxieties of the age – through the distortions of her face, a charged palette and the strong black lines that model the sweep of her thick hair, full breasts, signature hat and prominent, expressive hands. When she and Picasso met at Les Deux Magots she had repeatedly driven a small, pointed penknife into the table between her gloved fingers, sometimes drawing a drop of blood, and Picasso would later ask for those gloves as a memento. Strikingly, Jean-Paul Crespelle, who recorded that first meeting at the café, also described her face as sensitive and uneasy, ‘with light and shade passing alternately over it’.

The fate of this canvas was unusual. Confiscated by the Nazis from Picasso’s Jewish dealer Paul Rosenberg in 1940, four years later it was part of a transport of masterpieces stored in the Jeu de Paume that were intended for Germany, a consignment held up through a barrage of red tape orchestrated by the Free French Forces – Alexandre Rosenberg, Paul’s son, among them. A brilliant ploy, it was nonetheless rather less exciting than the tale as dramatised in the 1964 film The Train, starring Burt Lancaster and Jeanne Moreau. Estimate $35m–$50m.

At the time of writing, Sotheby’s had not released information on its May highlights. Christie’s announced that the firm was cancelling its June post-war and contemporary sales in London in order to concentrate on its March and October offerings, but would continue to stage its summer Impressionist and modern auctions.

Elui, son of Nzenge Mkambo from Voi (Tsavo lowlands) (1962), Peter Beard. Sotheby’s London, estimate: £70,000–£100,000

Not everything in the saleroom comes with estimates of millions. London sees various sales around the third edition of Photo London at Somerset House (18–21 May). Africa plays an arresting role in Sotheby’s 19 May offering. Elui, son of Nzenge Mkambo from Voi (Tsavo lowlands) appeared on the cover of Peter Beard’s seminal book The End of the Game, published in 1965, which documented the demise of elephants and other African wildlife. Here Elui squats, holding an enormous tusk, the photograph itself annotated by Beard and framed in blood (estimate £70,000–£100,000). Pieter Hugo’s no less provocative documentary photographs take as their subject the continent’s marginalised people. Most compelling is his monumental C-print Abdullahi Mohammed with Mainasara (The Hyena and Other Men), Lagos, Nigeria of 2007 (estimate £20,000–£30,000).

From the May issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.