From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1949, the Calico Museum of Textiles, in the Calico Mills compound, was the first modernist building in Ahmedabad, the centre of textile production in Gujarat that was known in the 19th century as the ‘Manchester of India’. It was designed by the intensely private architect Gira Sarabhai (1923–2021), whose contribution to Indian modernism is insufficiently recognised. The youngest child of the textile magnate Ambalal Sarabhai, she also curated the new museum’s unrivalled collection of Indian historic and contemporary fabrics, intended as a research collection that would aid the improvement of Indian design.

The Sarabhai patriarch was a prominent supporter of India’s Independence struggle and of Mahatma Gandhi, whose ashram was in Ahmedabad. However, as a moderniser and the first person in the city to own an automobile, he did not share Gandhi’s fetishisation of the spinning wheel and village life. His children were home-schooled in the Montessori method before being sent to study in the West. (Only Gira’s sister Mridula refused, faithfully sticking to Gandhi’s boycott of foreign goods and institutions.) The Sarabhais all returned to India to contribute to Jawaharlal Nehru’s post-Independence project – Nehru was a family friend – and cemented their reputation for patronage as the ‘Medicis of Ahmedabad’.

Gira Sarabhai trained as an architect under Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West in Arizona, where she worked on the spiral shell design for the Guggenheim. In 1946, she commissioned Wright to design an administrative office and store for the family firm in Ahmedabad, but it never got off the drawing board. On returning to India after Independence in 1947, and having fallen out with Wright, Gira switched allegiances to Le Corbusier, who had been invited by Nehru to build Chandigarh, the first modernist city to be built from scratch. In 1951 she invited Le Corbusier to Gujarat hoping that he might be persuaded to build a house for her recently widowed sister-in-law, Manorama, and her two children.

Le Corbusier ended up building two luxury villas in Ahmedabad as well as the Sanskar Kendra museum and the Mill Owner’s Association Building, a porous cube the facade of which is covered in a sun breaker or brise-soleil that also serves as planters for hanging gardens. He had a mystical conception of India and hoped that in the tropics an alternative modernity might develop and avoid the mistakes of a capitalist West with which he was increasingly disillusioned. Architects such as B.V. Doshi, who worked in Le Corbusier’s Paris studio (unpaid for the first eight months) and returned to India as site architect for these projects before setting up his own practice in Ahmedabad, took Le Corbusier’s lofty grammar and infused it with a more democratic spirit.

Gira’s nephew, Suhrid Sarabhai, recently invited me for a tour of the Villa Sarabhai on his family estate (‘the Retreat’). He showed me a letter from his aunt to Le Corbusier thanking him for sending a book about himself and confessing, bluntly, that she won’t read it as she does not understand French. The Villa Sarabhai is open plan, with a series of tiled barrel vaults that look on to a verdant garden, closed to the elements only with bamboo blinds. There is a photograph of Suhrid with Le Corbusier and Doshi discussing the 45-foot slide that comes down from the roof, which was Suhrid’s idea, dropping into a swimming pool that Corbusier had argued should be bigger.

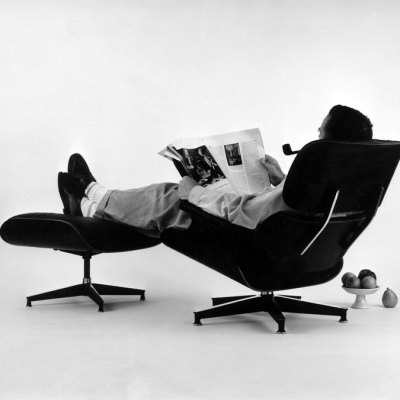

To the Retreat, Gira Sarabhai invited Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, John Cage, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames for residencies in a garden studio. In 1958, Nehru commissioned the Eameses to write their India Report, which recommended a school of design on the Bauhaus model with students ‘learning by doing’. The National Institute of Design (NID) opened in 1961. Its first home, funded by the Sarabhais, was in a studio at Calico Mills before it moved to Le Corbusier’s empty museum building. In 1966 Gira and her brother Gautam, a Cambridge-educated mathematician, completed a new campus for NID on the banks of the Sabarmati river, with courtyard teaching spaces and a roof of elegant brick dome vaults.

In 1962 Doshi also established and designed a separate School of Architecture in Ahmedabad, with an open under-croft for teaching and breezy, interconnected studios. NID students embarked on fieldwork to document and upgrade traditional Indian crafts, and from Doshi’s architecture school students travelled India to measure and record the country’s step-wells, mosques and temples, and to study rural villages and towns. Reacting to Chandigarh, which discouraged mixed-income neighbourhoods and informal street markets, Doshi’s buildings and housing developments sought to reintroduce the vitality of India’s public spaces into a sterile modernism.

One of NID’s first projects was the creation of the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), established by Gira’s eldest brother, the physicist and astronomer Vikram Sarabhai, who initiated India’s space programme. Working with NID students and faculty, Doshi served as Louis Kahn’s project architect. Kahn created a red-brick behemoth, punctuated by huge round, semi-circular and square windows.

Much of Nehru’s heritage, including his founding vision of a secular country, is currently under threat. While Doshi’s School of Architecture has recently been sensitively restored, at IIM students and faculty have vacated Kahn’s badly maintained building. While a last-ditch campaign to save it is led by the alumni body and international architects and conservationists, it stands as eerily empty as a de Chirico painting. Le Corbusier’s museum is also closed, supposedly under restoration but with little evidence of any work being done. Gira and Gautam Sarabhai’s Buckminster Fuller-inspired Calico Dome (1963), the first space-frame structure in India, collapsed in an earthquake in 2001; its court-ordered restoration has also stalled and is incomplete.

‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence’ opens at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in March 2024.

From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.