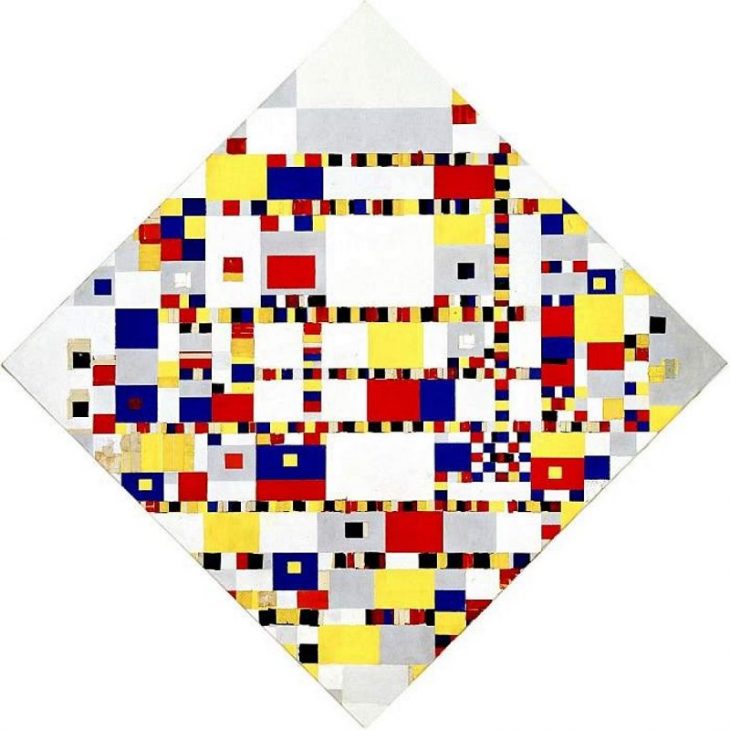

Benno Tempel, the director of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, has a prized photograph fixed to the back of his computer monitor – Barack Obama standing in front of one of the museum’s most important paintings: Piet Mondrian’s Victory Boogie Woogie (1942–44). In 2014, The Hague hosted the Nuclear Security Summit and the final press conference took place in the museum’s courtyard, which had been speedily covered over with a permanent glass roof for the event. I am meeting Tempel in mid January, the day before the inauguration of the 45th president, and am curious about Obama’s visit. His speech was longer than expected, Tempel says, and his entourage ‘was pulling at his arm when he finished and came off stage’. The president, however, insisted that he wanted to see the painting and when he walked into the gallery said, ‘Ah, the fabulous one!’

When Tempel’s predecessor at the Gemeentemuseum acquired Victory Boogie Woogie in 1998, from S.I. Newhouse, president of Condé Nast, for $40 million, it was the most expensive painting a Dutch museum had ever bought. Since the Dutch national bank had donated the sum for the purchase to the Dutch National Art Foundation, it was a state-funded acquisition, which some observers – and the body that scrutinises government spending – thought inappropriate. The chief curator of the Rembrandt House said at the time, ‘We could have acquired at least two good Rembrandts for that price.’

But for the Gemeentemuseum, which already held the largest collection of Mondrians in the world, it was an essential acquisition. Victory Boogie Woogie is the only painting by Mondrian from the 1940s in a Dutch museum and it will be the centrepiece of this summer’s ‘The Discovery of Mondrian’ exhibition (3 June–24 September), for which every single one of the Gemeentemuseum’s more than 300 works by Mondrian (including 163 paintings) will be on display. This event is part of ‘Mondrian to Dutch Design: 100 Years of De Stijl’, the year-long nationwide celebration of the country’s most important avant-garde movement.

Composition No. 8 , 1917, Bart van der Leck. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

In October 1917, the first issue of a magazine called De Stijl (‘style’) was published in Leiden, the home city of its editor Theo van Doesburg. It was a diffuse kind of avant-garde, since of its three leading figures, van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian, and Gerrit Rietveld, two (Mondrian and Rietveld) never met. Early adherents, such as the painter Bart van der Leck and the architect and planner J.J.P. Oud were also quick to distance themselves from the movement, or perhaps just from van Doesburg who, like many artists with enough will-power to form an avant-garde, had a talent for falling out with his peers. If the paintings, furniture, and architecture produced by this circle have any unity, it derives from their combination of sources – the neoplatonic philosophy of M.H.J. Schoenmaekers, who coined the term ‘neoplasticism’ (taken up by Mondrian) and argued that ‘the three principal colours are essentially, yellow, blue, and red’, and the buildings and spatial theories of Frank Lloyd Wright.

The cover of the second issue of De Stijl, published in December 2017. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

For Tempel, the De Stijl centenary is a chance to celebrate the strength of Dutch museums, as well as the legacy of the movement. In a meeting a few years ago, he explains, ‘I found other museums saying, “Are you going to do something about the De Stijl year?” […] Everybody had a theme already that they wanted to organise an exhibition about. We more or less made a calendar dividing up the year.’ The Gemeentemuseum will be hosting three exhibitions: as well as showing its entire collection of Mondrians, it will explore the links between Mondrian and Bart van der Leck (12 February–21 May) and the architecture and interiors of De Stijl (10 June–17 September). There will also be exhibitions at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, the Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, and in the cities of Leiden, Amersfoort (Mondrian’s birthplace), and elsewhere. ‘It’s very good that you can see the strength of the collections,’ Tempel says. ‘The Dutch museum system is one of the most beautiful in the world. There are very few countries that come up with the number of museums we have – but the number is not interesting, it’s the quality.’

Even in such a thriving ecosystem, the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (the Municipal Museum of The Hague) is singular. The museum building is a display case for modern and contemporary fine art and applied arts, and a significant work of the modern movement in its own right. In 1919, the city council commissioned Hendrik Petrus Berlage, the great Dutch architect whose other masterpiece is the former Amsterdam Stock Exchange building, to design a museum for its historical art collection. The architect’s first scheme for the Stadhouderslaan site was a much larger museum complex including a concert and congress hall. In 1927, Berlage presented a simpler plan and construction began in 1931, though the architect died a year before the work was completed in 1935 and the museum opened.

The entrance of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. photo: GAPS

Although Berlage scaled back his original plan, the Gemeentemuseum is full of quietly theatrical moments. The entrance to the museum consists of two pylons in front of a covered walkway, on either side of which are two large rectangular ponds (frozen over when I visit). The harmony of the building lies in its ingenious grid system – all its volumes are based on a 110 x 110cm grid and the non-standard ochre-brick used on the exterior was made specially for the museum. In the foyer, the walls are painted white and edged with strips of yellow tiles with black borders, and smaller areas of green; the floors are tiled in green and terracotta and all the door and window frames are a bronze-patinated brass – as are the edges of the display cases Berlage designed for the ground-floor decorative arts galleries.

But it is the circulation, the route around the museum, and from one room to another, which is the most remarkable element of Berlage’s design. The fine arts galleries on the first floor are arranged in concentric rings around the inner courtyard. What this means in practice is that you can walk round the rings, or free yourself from the enfilades and cut through the galleries, and every room receives natural light, either diffused through suspended glass ceilings or indirectly from a corridor. As Tempel says, ‘The way the museum is built doesn’t make you fatigued. Often when you visit […] a very large museum, you go in with a lot of enthusiasm and a few hours later you come out exhausted. That is almost never the case here as the rooms are not so big. You always have a vista into the next gallery, but because the rooms differ in size, it is like an organism […] like lungs, or a heart pumping.’

The director’s office is right at the heart of the museum, above the main foyer with a view looking out over one of the ponds. Tempel enjoys the location: ‘I constantly meet the public, which can be the general public, a journalist, a collector, an artist, a colleague from abroad. I’m absolutely sure that at least every week, things come from this, maybe sometimes every day.’ A specialist in 19th-century painting, he became director of the Gemeentemuseum at the start of 2009 and has thrown himself into creating enthusiasm for the museum’s permanent collections, expanding the scope of its exhibition programme, and getting the attention of younger visitors. It’s hard, for instance, to think of any another major museum director (or art historian) being so enthusiastic about the Gemeentemuseum’s immersive Wonderkamers project.

View of one of the fashion galleries in the Wonderkamers installation at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

In the basement of the museum, this game installation begins with an animated film, in which a cartoon form of Benno Tempel runs across the screen and explains the concept. At the centre of the main room, is an installation called the Magic Middle, filled with miniature artworks, by artists ranging from Yves Klein to Marlene Dumas, from the collection of Ria and Lex Daniels. Around this display, are a series of rooms filled with displays made from the museum’s collection of decorative and applied arts. Equipped with a tablet, visitors can identify the pieces, collect points, and make a new virtual gallery of their own. I make a foray into one of the fashion displays, installed in a mirrored room somewhere between a work by Yayoi Kusama and Studio 54, but don’t have the time to spend on the game that it clearly requires. The face of the museum’s director (in a choice of costumes) is the visitor’s avatar on the screen, so the reaction he reports from some visitors is understandable. ‘I walk through the galleries,’ Tempel says, ‘and small children come up to me and say, “Hey, you’re Benno. I want to be a director also!” Boys are not saying, “I want to be a policeman.” They want to become a museum director. That’s great.’

Tempel’s second life as a Lichtenstein-esque cartoon does not mean that he is not deeply engaged with the most traditional aspect of being a museum director: stewarding and making sense of the permanent collection, and deciding what to add to it. The Gemeentemuseum has never tried to be an encyclopaedic museum. The 19th-century municipal art collection was heavily influenced by the tastes of the museum’s Association of Friends, which celebrated its 150th anniversary last year, and bought works by members of the Hague School, such as William and Jacob Maris and Anton Mauve. And the 20th century, apart from its great haul of Mondrians and other De Stijl works, has strengths in Expressionism. ‘So Pop art, you will not find it here. Surrealism, you will not find it here. […] It also means that when someone says, do you want to organise an exhibition with us about Surrealism, I say, please go to my colleagues in Rotterdam – they have the most beautiful collection of international Surrealism.’ Minimalist works like Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings, however, are well suited to the museum and its architecture; as are Fred Sandback’s yarn sculptures.

One thing Tempel has noticed is that many of his predecessors ‘looked back’ when they made their major acquisitions, often to 40 or 50 years before. ‘They probably paid too much, but on the other hand, the dust of history has settled a bit and you can better see what you think is an important artist of the period.’ This time-lag approach means that Tempel is now turning his mind to the period between 1965–85. The museum has recently acquired 13 works by the Japanese Gutai group artists and will be displaying them in a room with two Dutch artists: Jan van Schoonhoven, who showed with the same Hague gallery as the Gutai artists and Daan van Golden, who lived in Japan in the 1960s.

Portrait of Edith (The Artist’s Wife) , 1915, Egon Schiele. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

When I press Tempel for his favourite works in the museum, he says ‘Of course I like the Mondrians.’ Switching to connoisseurial mode, he adds. ‘One of the things few people understand is that of all the things he is, most of all he is a painter. It’s about paint and its about the reflection of light, the way light is reflected into the room, and that’s what makes his paintings so great.’ He also singles out Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon project: ‘I think after Mondrian, it’s the best thing by a Dutch artist in the [20th] century.’

There’s an enjoyable irony in the fact that Berlage had little fondness for the output of De Stijl. Despite his own influence on the modern movement – and his role in spreading the influence (and technical innovations) of Frank Lloyd Wright – he was particularly hostile to abstract art, which he viewed as the enemy of his ideal of gemeenschapskunst – art for the community. And in 1922, when giving a lecture titled ‘Art and the Crisis’ in The Hague, the art he referred to as evidence for the crisis was Mondrian’s Composition in Colour A (1917).

But the Gemeentemuseum is more than a meeting place for tensions in Dutch modernism. It offers its visitors more literal juxtapositions, too. Tempel reminds me that in the Netherlands, the three largest modern art museums collect decorative art as well as fine art, ‘which is not the case in the UK, it’s not the case in Germany, it’s not the case in Belgium. It’s a very Dutch situation.’ The museum has the largest fashion collection in the country and a growing reputation for its fashion exhibitions, often in collaboration with French couture houses. The different audiences that come for the museum’s many temporary exhibitions ‘get a lot of surprises’ thanks to the layout of the upstairs galleries. ‘If you come here for Givenchy and you’re only interested in fashion, I’m absolutely sure that you will see a few paintings and a few works of art. Maybe you never dreamt of looking at a work of art when you left your home to visit the Gemeentemuseum, but that’s the surprise we can offer you.’

Victory Boogie Woogie, 1942–44, Piet Mondrian. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

My own wander round the galleries bears this out – since the rooms are small and each room has a view into another, there are plenty of intriguing contrasts. Visible through the glass door of a room full of mannequins clothed in Givenchy and soundtracked by music from Audrey Hepburn films are some of the Gemeentemuseum’s 20th-century treasures, including Egon Schiele’s Portrait of Edith (1915). Tempel calls her one of art history’s ‘magic ladies’, but unlike some of the others, such as the Mona Lisa and the Girl with a Pearl Earring, it’s perfectly possible to find yourself alone with her, as I do.

As for the ‘fabulous one’, Victory Boogie Woogie is too fragile to travel and will never leave the Gemeentemuseum. ‘Mondrian painted it in the free world, in the last years of the war. For the last two years of his life he only worked on this painting, which was rare […] But he knew he was going to die and he hoped to finish it. If you compare it with the last paintings of Van Gogh, which seem to be drowned in depression, soaked by sorrow, here it is the opposite. He knows he’s going to die and it is vibrant and lively and energetic.’ The photograph of Obama and the painting has been fixed to Tempel’s computer since the visit. Will it stay there? ‘Oh, absolutely – I thought it was very inspiring […] talking about Mondrian, but also about the museum. Let’s say until the next president comes, but I don’t think he will.’

‘The Discovery of Mondrian’ is at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, from 3 June–24 September. ‘Mondrian to Dutch Design: 100 Years of De Stijl’ is at museums throughout The Netherlands in 2017.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.