The American Museum of Natural History has announced that it is offering free entry to people eligible for food stamps as part of the nationwide Museums for All initiative. It is not the only New York institution to have put this policy in place: the Frick Collection, the Museum of Modern Art and the Morgan Library & Museum are among those participating. While Rakewell is always pleased to see museums find ways of allowing more people to visit their exhibits, this announcement is particularly exciting, for the AMNA’s glorious Gilded Age building on Central Park West contains a particularly valuable display. Many visitors come to look at the 28-metre-long model of the blue whale or the skeleton of the Tyrannosaurus Rex, but Rakewell always starts a visit to the AMNA with a trip to the dioramas.

Very little stirs the soul in quite the same way as the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals. This is no mere museum installation but one of the finest unions of art forms: artists, taxidermists, set designers and sculptors came together in the early ’40s to create what might be America’s finest Gesamtkunstwerk. It takes particular skill to make what is essentially a teddy-bear version of a coyote appear to be howling in the wild, or a caribou looking over its shoulder at the horizon conjure the illusion of distance. In some of the installations, if you look very carefully, you can see where real sand meets paint to convey a sense of boundless nature. Keep an eye out, also, for the northern flying squirrel.

This has made Rakewell think about other triumphs of the dioramic art in museums. The delightfulness of the diorama is not always proportionate to the skill of manufacture. One diorama at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale delle Marche in Ancona shows how Stone Age people inhabited the hills of Le Marche. The materials are less dramatic than AMNA’s – the dead stag that is presumably about to be eaten by its bearers is nothing more than painted wood – and yet in its simplicity there is something strangely evocative, if only of kindergarten history lessons.

One favourite of Rakewell’s can be found in the attic of Les Invalides in Paris. The Musée des Plans-Reliefs is an extraordinary collection of models of fortified towns in France, many of them commissioned by the court of Louis XIV to plan defences in a time of war. Nestled in a corner of the museum is a particularly remarkable example: an exact replica of Mont-Saint-Michel, built by a monk as an act of devotion and made, in places, out of playing cards.

If making a diorama is the making of a miniature world, Rakewell would like to alert readers to the art of dressing fleas in clothes by suggesting a visit to the Natural History Museum in Tring. The museum also contains avian dioramas, fixing a world of flight and movement behind glass for all amateur naturalists to appreciate.

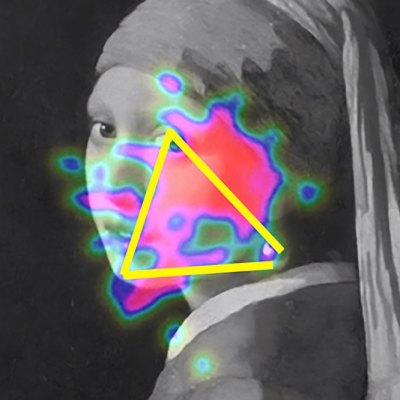

Perhaps this is why dioramas are so attractive – their ability to hold the motions of the world still for a moment so that viewers can appreciate details that might otherwise be missed. And verisimilitude demands its own sort of respect, which brings us to what might be considered the original diorama: Samuel van Hoogstraten’s perspective box (c. 1655–60), which allows you to look in through a peephole and see an entire house in one black box. Dioramas are increasingly considered museum pieces in their own right as video takes over, but as van Hoogstraten’s painted box shows, when you capture life precisely it can be mesmerising and moving – even if the image itself doesn’t move.